[ad_1]

Intel Corporation

So far 2020 is a tough year for Intel CPU amateurs“Both ways of the word.” Chipzilla’s new generation of desktop CPU has arrived, and Intel is struggling to find ways (mostly overclocking) to make them look good compared to AMD’s 7nm Zen 2 pieces.

The tenth-generation parts Core, Pentium, and Celeron follow the trend established by the recent launch of the H-series of Intel notebooks: they are old process technology tuned to less than an inch of their lifespan, and Intel still doesn’t offer numbers. performance could be compared directly to the competition.

Performance

-

Intel is relying heavily on raw clock speed with Comet Lake’s new S-series, just as they did with parts of the H-series laptop earlier this year.

Intel Corporation

-

Although Intel gave us performance deltas year after year this time, they are still avoiding the hard numbers.

Intel Corporation

-

Always read the fine print. The apparent legal inability to say “the fastest game processor

Intel Corporation

-

To Intel’s credit, they didn’t play GPU games here like they did with H-series laptops. All system setup includes an RTX 2080Ti.

Intel Corporation

For the most part, pre-launch benchmark data from Intel looks like what we got for Comet Lake H-series laptop CPUs – a sharp focus on unrated clock speed and a healthy smudge of Vaseline on the lens when observing actual performance. Once again, we are seeing single core turbo speeds in the highest SKUs exceeding 5 GHz, and a noticeable deviation from hard performance data that could be directly compared to AMD’s 7nm Ryzen CPUs.

To Intel’s credit, we have at least some performance deltas from generation to generation this time. However, we still have almost no difficult performance numbers, let alone direct comparisons with AMD Ryzen. Intel is also very interested in comparisons to a “three-year-old PC”. Presumably, they expect people who aren’t up to date on the Intel-AMD rivalry to just think, “yes, that sounds good, let’s go ahead and update this year.”

This time, Intel’s marketing relies heavily on its optimization collaboration with game development companies, as well as, if not more, on the gross performance of the new CPUs. But without direct head-to-head comparisons to Ryzen processors, it’s impossible to determine if the brilliant testimonials from gaming companies about Intel’s help apply to Intel vs. AMD, or just the newer generations versus the older ones.

The gaming and gaming marketing approach with this series of CPUs is extreme and predictable: single-threaded performance is almost the last place where Intel can expect to compete directly against its AMD competition, and it’s hard to find someone who worry a lot about that statistic outside the gaming world.

Modern content creation and workload compilation tend to be massively multithreaded and focus more on performance than latency. Games, particularly higher levels of competitive games, tend to be more influenced by input and response latency. If a single core can traverse the main circuit of a faster game, an elite player may lose an extra few milliseconds of reaction time.

Trying to assess the real benefit of the fastest CPU games possible is made more difficult since none of the typical industry metrics measure this well: frames per second is a performance metric, not a latency metric. To make matters worse, FPS is generally displayed as a mean average, rather than a median or mode. It focuses heavily on the graphical dimension of the game cycle while effectively ignoring input and logic.

Questions about metrics aside, presumably some of Comet Lake’s new S-series performed better frame rates than their Ryzen equivalents, at least in all three games Intel tested. We are forced to guess this, due to the fact that Intel lists a Ryzen 9 3950X configuration on one of the “small print” slides.

We can also assume that this was not a particularly compelling difference and that it may not hold broadly between most games. Another of the small print slides points out that Intel’s marketing slogan for EE. USA “World’s Fastest Game Processor” Cannot Be Used in an Amazing List of Countries; in those countries, it is replaced with “Elite Real World Performance” or “Intel’s fastest game processor.”

Yes, yes, we know, here we are reading marketing tea leaves. But without hard data, they are all we have to follow.

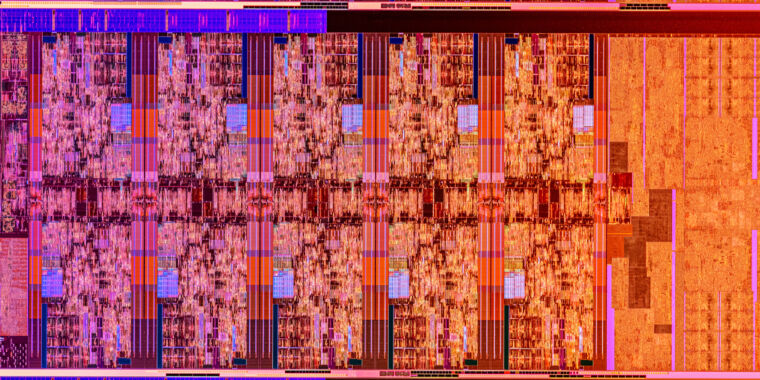

Architecture

-

Officially supported DDR speeds still lag behind Ryzen (DDR4-2933 vs. DDR4-3200). Overclocking adjustments, and the need for a new socket, are the most important story here.

Intel Corporation

-

Turbo Boost Max automatically identifies and boosts the two fastest cores in the individual CPU, rather than a fixed pair.

Intel Corporation

-

Overclocking becomes more accurate with Comet Lake S, including the ability to disable hyperthreading on individual cores, rather than the entire CPU.

Intel Corporation

-

Thinning the die allows the use of a thicker built-in heat diffuser, thus potentially better cooling for the hotter parts of the die.

Intel Corporation

First off, if you want a tenth generation Intel desktop CPU, you will need to purchase a new motherboard. The new CPUs are designed for an LGA1200 socket, rather than LGA1154. These will not be a direct replacement for anyone.

Beyond that, we’re mostly just looking at overclocking tweaks. Turbo Boost Max 3.0 dynamically selects and boosts the two fastest cores on a given individual CPU, and there are plenty of new knobs for hard overclockers to turn in Extreme Tuning Utility, such as the curious ability to enable or disable hyperprocessing on core individuals , not just the CPU as a whole.

The i9 series (and only the i9 series) also features a new Thermal Velocity Boost feature, which can get an additional 100MHz for short periods of time while the CPU is generally cooling down.

Intel has also slimmed down the CPU array on some models, allowing for a thicker built-in heatsink, and therefore potentially better cooling in the hottest operating areas in the array. We don’t have much specific information about the new weight loss process, and we don’t know for sure which models it applies to.

The officially supported RAM speed has also been increased a bit, from DDR4-2666 to DDR4-2933. It still lags behind the Ryzen 3000 DDR4-3200.

[ad_2]