[ad_1]

EVEN IN HALF a century, there are more questions than answers about what happened at the Gresham Hotel on November 21, 1920.

By 9 a.m., IRA assassination teams were moving into positions throughout the city, most of them in a small area of the southern city center.

Reading directions today (Lower Baggot Street, Earlsfort Terrace, Upper Mount Street, Morehampton Road) it’s almost claustrophobic to imagine the area of the slaughter that morning. But the Gresham, on the other side of the Liffey, was geographically removed from much of the action.

James Cahill, one of the IRA men sent to the hotel, later recounted that “three groups, of three men each, were designated to carry out the shooting. The rest of our group was assigned the task of monitoring hotel staff members and residents, covering exits and avoiding communication with the outside during the operation. “

As Cahill recalls, they had been sent to the hotel to eliminate “three intelligence officers residing at the Gresham.”

Within minutes, two men died at the hotel. Cahill recalled entering the room of one of the targets, Captain Patrick Joseph MacCormack. Sitting on the bed, MacCormack fired a shot at the assault group, “We fired almost at the same instant, killing him directly.”

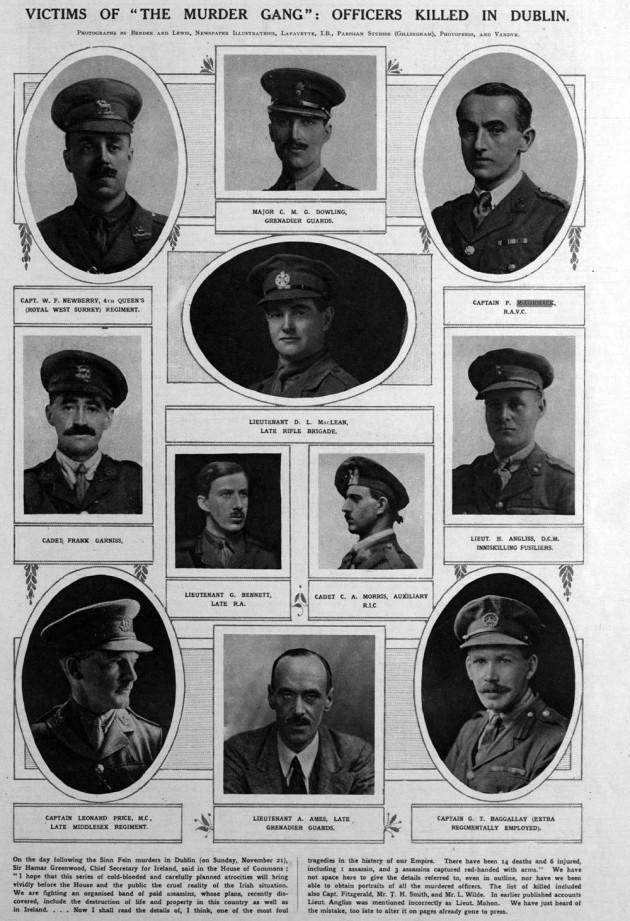

Some of the victims of Bloody Sunday

Source: Donal Fallon

In the hotel corridor, the IRA group came across another man, who introduced himself as “Alan Wilde, British intelligence officer, fresh from Spain.” They shot him, dying instantly.

The Mystery of MacCormack and Wilde

In the years that followed, the MacCormack and Wilde families insisted that their loved ones were not Secret Service agents. MacCormack was a qualified veterinarian and respected athlete who had joined the Royal Army Veterinary Corps.

His mother, who later wrote to Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy for answers, was informed that there was no particular charge against him except “that he was an enemy soldier.”

Wilde proved even more perplexing, and although he had a checkered British Army past, it is still unclear what he was doing in Dublin.

Three days before his death he had written to Arthur Henderson of the British Labor Party, telling him that as an eyewitness to what was happening in Ireland, “I must say first that it is not British rule and second that Ireland will not be coerced. Ireland is essentially a tradition-loving people and its traditions must be respected by those who govern it. “

Perhaps Wilde, in his innocence, felt that he could solve the Irish problem; three days later, it was fatal. The question remains, had he panicked seeing the men in the hall that day, presuming they were policemen, and had he told them what he felt they wanted to hear?

One bloody fateful morning

There are no such mysteries surrounding most of the morning dead that we now know as Bloody Sunday, and that the British press dubbed Black Sunday. It marked a major escalation in an intelligence war that had been raging on the streets of the capital for more than a year.

Through targeted assassination, The Squad, a team of IRA assassins operating directly under the control of Michael Collins and his intelligence network, had neutralized the intelligence division of the Dublin Metropolitan Police throughout 1919.

But the men killed on Bloody Sunday morning were mostly of an entirely different race, high-level intelligence agents that Collins felt should be eliminated from the scene.

Some of The Squad, including Vincent Byrne (center)

Source: Donal Fallon

Reflecting on that need, Collins would insist that “my ultimate goal was not to achieve it simply by exceeding [The British Secret Service] out of stock, he wanted to replace it with a better Irish secret service. The way to do it was obvious and naturally divided into two main parts: making it unhealthy for the Irish to betray their fellow men and making it deadly for the English to exploit them. “

Collins argued that the death of an intelligence agent was a hammer blow compared to the death of a soldier, since “even when the new spy put himself in the shoes of the old man, he could not enter the knowledge of the old man.”

The twelve apostles

The men Collins recruited into The Squad were mostly young volunteers, some still in their teens. Despite this, they were often already veterans of violence, as survivors of the 1916 Uprising. There is an indifferent coldness to how some of them later spoke of their work; Vinnie Byrne tells historian Tim Pat Coogan:

We were all young, twenty, twenty-one. We never thought we would win or lose. We just wanted to give it a try. We’d go out in pairs, walk to the goal and do it, then split up … In a typical job, we’d use about eight, including backup. No one got in our way. One of us knocked him down with the first shot and the other finished him off with a shot to the head.

The counterintelligence war fought by Collins on the streets of Dublin was multi-faceted. Charlie Dalton, barely a teenager on Bloody Sunday morning, recounted that “we compiled a list of friendly people in the public services, railroads, mail ships and hotels. They constantly sent me to interview butlers, journalists, waiters and hotel porters to verify our reports on the movement of enemy agents ”.

Perhaps the most important help at his disposal was Lily Mernin, a typist at Dublin Castle, who had access to the internal documentation that was crucial in compiling the Bloody Sunday hit list.

The Squad consisted of just a dozen handpicked operatives, earning it the nickname The Twelve Apostles. An operation like Bloody Sunday required more hands. Seán Russell of the IRA, a 1916 veteran and later IRA Chief of Staff who sought military aid from both Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany, was tasked with finding the additional men.

One volunteer recounted the tensions the night before the operation, as Russell told them it was “vitally important to the success of our fight that they [the spies] To be removed; that no country had scruples in shooting enemy spies in times of war; that if any man had moral scruples to undergo this operation, he was free to withdraw and no one would think the worst of him; that he wanted every man to be satisfied in his conscience that he could properly participate in this operation. “

No news is bad news

Support the magazine

your contributions help us continue to deliver the stories that are important to you

Support us now

Some IRA men struggled with what they were asked to do: Charles Dalton recalled that he sat down the night before and “was upset, thinking about what we had to do the next morning, and the other men might be the same. “

But on the day itself, there was a kind of adrenaline rush that moved through all of them. In the words of Frank Thornton, they knew that they had been asked that day “to do something that was beyond the ordinary scope of the soldier.”

The dead from the morning murders

The IRA accounts that arrived at the addresses that morning survive from both sides of the doors being opened. Vinnie Byrne recalled arriving at 38 Upper Mount Street, where two alleged Secret Service agents resided:

I ordered the British officer to get out of bed. He asked me what was going to happen and I replied: ‘Ah, nothing.’ Then I ordered him to march in front of me … I led my officer to the back room where the other officer was.

He was standing on the bed, facing the wall. I ordered mine to do the same. When the two were together I thought to myself ‘The Lord have mercy on their souls! So I opened fire with my Peter. They both fell dead.

At 117 Morehampton Road, Thomas Herbert Smith, the owner, is shot by a assault group. He is a forgotten and accidental civilian victim of the morning. Smith’s wife later told the investigation:

I saw some men climbing the stairs, who seemed to be about twenty, with revolvers in hand. Then they told me to raise my hands and my husband came out on the landing and asked for a little time to put on some clothes, which I was granted. Then I asked if I could go see my baby in the next room and I was roughly pushed towards her. Then I heard about eight shots.

In London, there was finally fury in the press over the events of that morning, but little sympathy from the political class, Hamar Greenwood told the King’s Private Secretary that he “was astonished at the carelessness of those who lost their lives yesterday morning. , Not even a single one”. one of them had a revolver, while he never goes to bed without a revolver by his side and always carries one on his person. ”

For Greenwood, men had been outmatched, beaten at their own game. For a government that referred to the IRA only as the ‘murder gang’ and insisted that it had ‘murder by the neck’, the events of that morning were proof that the IRA was a capable opponent not only in the rural terrain of guerrilla warfare but also in populated urban settings.

The Bloody Sunday drama, in those chaotic morning minutes, was just beginning.

Donal Fallon is a historian and host of the Three Castles Burning podcast, an episode of which explores the events of Bloody Sunday.

[ad_2]