The coronavirus rampage through California has now made it the worst natural disaster in the state’s history, and has fueled fires and earthquakes for decades. If the resurgence continues, it’s on course this year the third leading cause of death in the state, a wonderful potential milestone for a disease that was unknown nine months ago.

But the figures capture only a fraction of the pain caused by the virus, seen the long-term effects of health and the pain of survival, not to mention the social constraint.

On Thursday, the state passed 10,000 deaths to COVID-19, since Patricia Dowd, 57, of San Jose, became the first known lethality of the virus in the United States on February 6th. The death toll seems to be suicide, hypertension, flu and diabetes to become the seventh leading cause of death in the state in just six months, judging from 2018 death toll numbers from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This number, 10,000, does not remotely represent the worst” coronavirus could do, said Dr. Steven Goodman, a professor of epidemiology at Stanford University. “It could easily be in a year at a level close to cancer or heart disease if we did nothing.”

Ironically, the 10,000-death milestone fell at a time when other coronavirus data in California were being called into question. Govin Gavin Newsom on Friday called for an investigation into computer system problems that appear to have compromised the state’s total tests and infections for at least the past two weeks.

The call came when California’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Dr. Mark Ghaly, broke the state’s silence over the system’s persistent technical problems with an overview of what led to the massive backup of data, which left counties in limbo as they relied on outdated spreadsheets to detect virus locally. Ghaly could not say for sure when all the problems will be fixed.

The call came when California’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Dr. Mark Ghaly, broke the state’s silence over the system’s persistent technical problems with an overview of what led to the massive backup of data, which left counties in limbo as they relied on outdated spreadsheets to detect virus locally. Ghaly could not say for sure when all the problems will be fixed.

“We are fully investigating how this communication could have been better and where it went wrong,” Ghaly said, adding, “we will hold people accountable.”

The problems, however, have not compromised the die numbers, and they are wonderful.

To put coronavirus in context, more than 62,500 people died of heart disease in California in 2018, the most recent year for which totals are available. Nearly 60,000 died of cancer, followed by 16,600 deaths from Alzheimer’s disease and 16,400 from stroke.

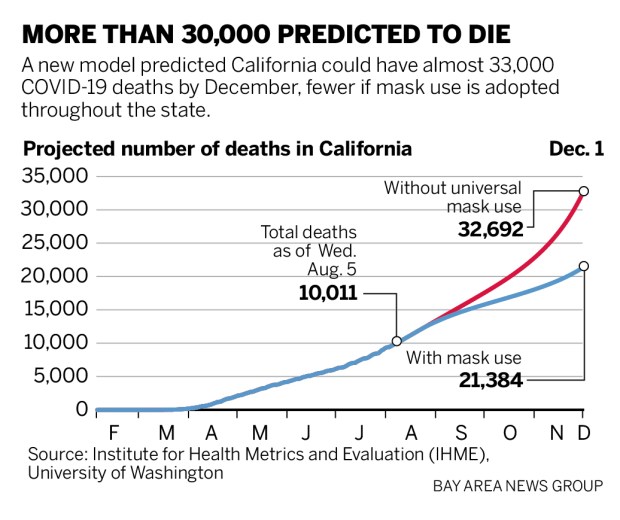

COVID-19 could soon overtake the last two of those – a new estimate released Thursday predicts that California could have nearly 1,700 deaths from the virus by December 1, even with the state’s current mitigation plan. The analysis, from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, predicting even with almost universal mask use, deaths on that date could reach about 21,400.

Nothing, other than perhaps climate change, has had such a profound impact on the state, Goodman said.

Wildfires, a deadly and ever-destroying presence in California, pale in comparison. The 20 deadliest wildfires in the state’s modern history claimed a combined 302 lives, according to CalFire. That includes 85 deaths at Camp Fire 2018 in Butte County, and 25 deaths at the Oakland Hills Fire in 1991. California currently averages about the same number of deaths as those 20 wildfires every two days.

The nearest natural disaster, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, is estimated to directly and indirectly claim 3,000 lives at a time when San Francisco had about 400,000 inhabitants. In addition to that infamous disaster, major earthquakes since the 1800s have claimed less than 500 lives in the state, including 63 during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Only two disasters have left the death toll of COVID-19 yet, but their records will fall almost this winter. In the 20 years after California became a state and gold was discovered, as many as 16,000 Native Americans were killed during a widespread genocide campaign against the region’s original inhabitants by new white colonists. And in 1918, the flu epidemic killed about 16,800 people in California – with another 13,000 deaths in the next two years.

For those affected by the virus, the cause of death is not the whole picture. In mid-March, Stacey Silva lost her father, Gary Young, a victim of the virus at a time when there were less than 1,000 known cases in the state. Young, who lived with Silva in her Gilroy home, was known to greet people with “good morning” at any time of the day, a guaranteed way to bring a smile to their faces, Silva said.

Silva said she has struggled with depression and guilt after the illness kept her from her father’s side when he died. She is also frustrated by people who oppose masking requirements that can help limit the spread of the virus.

“The pain I went through, the pain that my family went through, I would not wish that on my worst enemy,” she said.

It has also taken a financial toll. After news stories were published about Young’s death, Silva’s wife lost her job. Her wife’s boss, Silva, dismissed her because she had not informed him that she was connected to someone with the virus. They refused to name the company.

Even those who are cured of the virus could have lifelong complications. Doctors have reported people with damaged heart and lungs, dying problems leading to stroke and pulmonary embolisms among younger patients, Goodman said.

“Even for those who have survived, we are still trying to cope with what percentage of these have crashed or suffered permanent damage,” he said. “It’s difficult to get long-term results if the virus only exists for six months.”

Staff writer Fiona Kelliher contributed to this report.