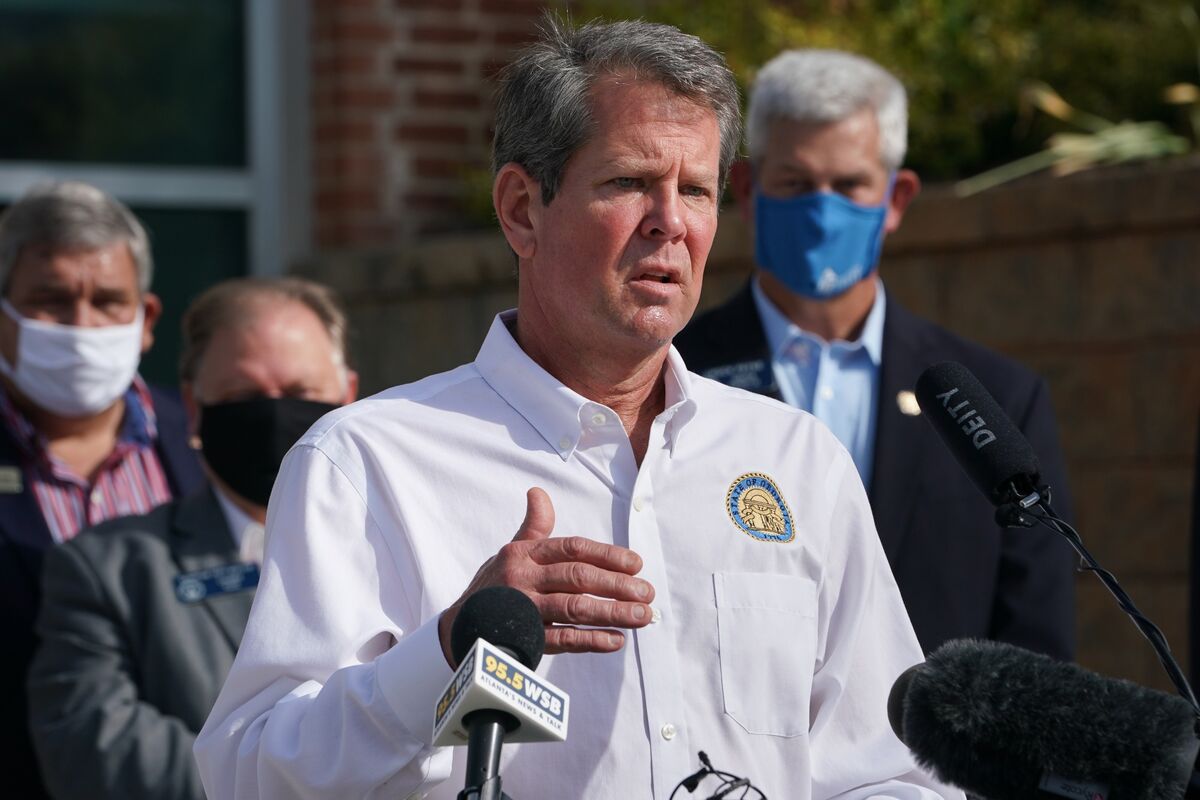

Brian Kemp speaks during a stop on the ‘Wear A Mask’ tour in Dalton, Georgia on July 2.

Photo credit: Elijah Nouvelage / Bloomberg

Photo credit: Elijah Nouvelage / Bloomberg

Sign up here to receive our daily coronavirus newsletter on what you need to know and Subscribe to our Covid-19 podcast for the latest news and analysis.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp’s edict, which expressly overrides local government coronavirus mask orders, limited a week of turmoil in a state that was once touted as proof that reopening in a pandemic could work.

For six weeks, Georgia had been a model, especially for those eager to end closings. Among the last U.S. states to close, Georgia was the first to reopen widely in April, after just three weeks. Critics said the state misrepresented its data to justify the move, and predicted the disaster.

It did not happen: Covid-19 case numbers increased, neither increased nor decreased significantly. Pandemic skeptics sang.

That ended last month.

Although they still lag behind Florida, Texas, and Arizona, Covid-19 cases in Georgia are emerging. As of Thursday, the seven-day moving average of recently reported cases by the state was 3,507, quadrupling its peak prior to the end of April. Last week, Georgia joined states whose citizens have to be quarantined if they visit the Northeast or Chicago. It also reopened a makeshift hospital overflow room at an Atlanta convention center when local governments tried to contain the increase.

However, on Thursday, the Kemp administration followed up on its mask nullification order with a lawsuit seeking to block the Atlanta requirement.

It was another example of it hampering local efforts, making it an atypical case among southern governors who have reversed reopens in the face of rising infection rates. The contrast speaks of a greater challenge for Republicans trying to fight the pandemic in the era of President Donald Trump.

“There is a tragedy in these red states that is the direct result of poor public health, security, and poor public policy decisions in an effort to please Donald J. Trump,” Anthony Scaramucci, former The White House director of communications became a critic, he said in an interview.

Read more: Hospitals to Redirect Covid Data to HHS on the Move to ‘Streamline’

Kemp’s office did not respond to a request for comment. But local leaders in Georgia said their hands have been tied by their state orders since late April.

“Helpless and demoralized,” as Russell Edwards, Clarke County Commissioner, described feelings. Many local officials believed that case counts were increasing even when Kemp used upbeat, official statistics from the state as reasons to keep the economy going.

But the same week that Kemp ordered the reopening, his administration began presenting data in a way that made the state appear healthier than it was, said Thomas Tsai, professor of Har Chan University TH Chan School of Public Health.

The technique consisted of rolling back new cases to the first symptoms or taking a test, rather than reporting them as reported to the state, as Georgia had previously done, and as most states do.

“It is deeply troubling,” said Tsai. “Of course, I can’t speak to motivation.”

A stylist cuts a client’s hair while another has his temperature checked at a barber shop in Atlanta on April 27.

Photo credit: Dustin Chambers / Bloomberg

The effect, as states were told to preach their reopens in two weeks of declining case numbers, was to make Georgia’s trends look better artificially. The state began adding new cases to past dates on its trend line, making current numbers too low and incomplete, Tsai said.

“What is misleading is that they shave for the past two weeks,” he said. “If you look at the last two weeks, it’s always very low. It always seems artificially like a downward trend. “

Seniority is valuable to epidemiologists, said Nancy Nydam, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Public Health. “The traditional way to view data during an outbreak is by the symptom onset date, which tells you more about when people are infected,” he said in an email.

But Tsai said the massaged trend chart seemed to dictate policy, and Georgia shouldn’t have changed counting methods halfway. She called the moment “suspicious”.

The methodology “may be accurate from the point of view of epidemiologists, but it is something else entirely to do this in the middle of a pandemic,” said Tsai. “It will always appear to be declining. You are constantly moving the goal posts. “

Even now, according to a daily comparison made by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the difference is surprising. A table based on the new cases reported had numbers that shot up through July 16. The state’s symptom-onset version showed they plummeted after July 2.

The newspaper’s chart counted 3,441 new cases Thursday. The “preliminary” number in the status table: 20.

Nydam of the health department said the state will change its methodology again soon, as symptom onset dates have become less relevant as more asymptomatic people are tested.

Customers sit next to the dining room at Marlow’s Tavern restaurant in Johns Creek, Georgia on May 6.

Photo credit: Elijah Nouvelage / Bloomberg

State counting methods may have obscured the spread of the pandemic, but other factors may have had real mitigating effects.

One was fear: Georgians didn’t run away when they allowed it, according to mobility data collected by Google. The move didn’t seriously accelerate until June and remains below pre-pandemic levels for all location categories except parks and homes.

Another was sobriety. Georgia did not open bars until June 1, making a broadcast site off limits. And Kemp’s restrictions on reopening other businesses, such as beauty salon masks, initially kept new infections low.

Many Republicans have argued that the police brutality protests in late May were to blame for the increase, although Tsai is skeptical: “None of us can prove whether it was the protests or not. But given what we know about the broadcast, the groups come from indoor events in environments with poor air circulation for an extended period. Outdoor protests don’t tick those boxes. ”

The truth is that cases began to increase in late June and increased in July, developments that even the massaged data could not hide.

This month, the state department of education and the The Georgia University System reversed careful reopening plans. The latter also prohibited universities from requiring masks in class, sparking fury in Athens, home of the University of Georgia, Edwards of Clarke County said.

“Some of the large-scale student bars have reopened, which science tells us is the highest risk activity,” he said. “There is a lot of apprehension in the community based on a current trajectory.”

On July 1, Savannah became the first Georgia city to rebel, demanding masks for citizens.

Kemp initially did not react. “We saw that and we said, ‘To hell with this,'” Edwards said. By Wednesday, Clarke County and at least 14 other locations had mask mandates.

That night, Kemp suspended any “law, order, ordinance, rule, or regulation that requires people to wear facial covers, masks, face shields, or any other personal protective equipment while in public accommodation or on public property.”

On Thursday, the 3,441 new cases reported brought the total to 131,275. More than 3,100 people in Georgia have died of the disease.

.