The Federal Bureau of Prisons reached a grim milestone on Saturday: 100 prisoners have died from coronavirus since the beginning of the pandemic. Among the dead are fathers and mothers, daughters and sons and brothers and sisters, none of whom was sentenced to death.

There are 122 facilities in the federal prison system that house nearly 129,000 prisoners across the country. According to the office, more than 10,000 inmates have tested positive for the virus at some point, and more than 35,000 have been tested.

Of the one hundred dead, three inmates have died from the virus. The first was Andrea Circle Bear, a 30-year-old mother who gave birth to her sixth child while on a respirator.

“I asked [hospital staff] if she knew about the baby and they said, ‘No, she’s been on a respirator,’ “Circle Bear’s grandmother Clara LeBeau told CBS News.” She never knew she had the baby and never had a chance to hold her. “The baby.”

Circle Bear was convicted of drug charges after she was caught distributing methamphetamine outside her home in the Cheyenne River Sioux Indigenous Reserve. In January, she was sentenced to 26 months in prison. In late April, she died after contracting the coronavirus, about four weeks after the birth of her daughter.

In March, the office had suspended all prisoner transfers in response to the pandemic. Despite this, Circle Bear was transferred from the Winner City Jail in South Dakota to the Carswell Federal Medical Center in Fort Worth on March 20, the office said in a statement. A week later, he was sent to a local hospital over concerns about his pregnancy.

Circle Bear was discharged but returned two days later, on March 31, after she developed a fever and a dry cough. She was put on a respirator on April 1, the same day she gave birth to her daughter, Elyciah Elizabeth Ann High Bear.

Three days later, Circle Bear tested positive for coronavirus. She died on April 28. The office said Circle Bear “had a pre-existing medical condition that the CDC lists as a risk factor for developing the more serious COVID-19 disease.”

LeBeau said he was not allowed to see Circle Bear when he picked up the boy in Texas. Throughout her granddaughter’s illness, she maintains that she never received word from the office that she was updated on Circle Bear’s condition and that her death was a surprise.

“I just hope that something can be done to help other families where they shouldn’t have to go through what I did,” LeBeau said.

The Bureau of Prisons rejected an interview request with Director Michael Carvajal and declined to comment as part of this story. The agency, according to its website, has modified several operations in an effort to curb the spread of the virus, including placing newcomers in quarantine and detecting them, in addition to suspending all visits.

Jennifer Jones learned that her father, Eric Spiwak, died two days after receiving a call from an unknown number in North Carolina. “It was a three-minute, 48-second conversation, and it will probably take me a full minute to realize that I’m talking to my dad,” she said.

“He is out of breath and says, ‘I’m sick,'” Jones said, describing what ended up being his last conversation with his father. She believes the call came from a prison burner phone and that her father called her because she was his power of attorney, “she begins to get on the list of everything she wanted me to do and can’t even get a whole sentence.”

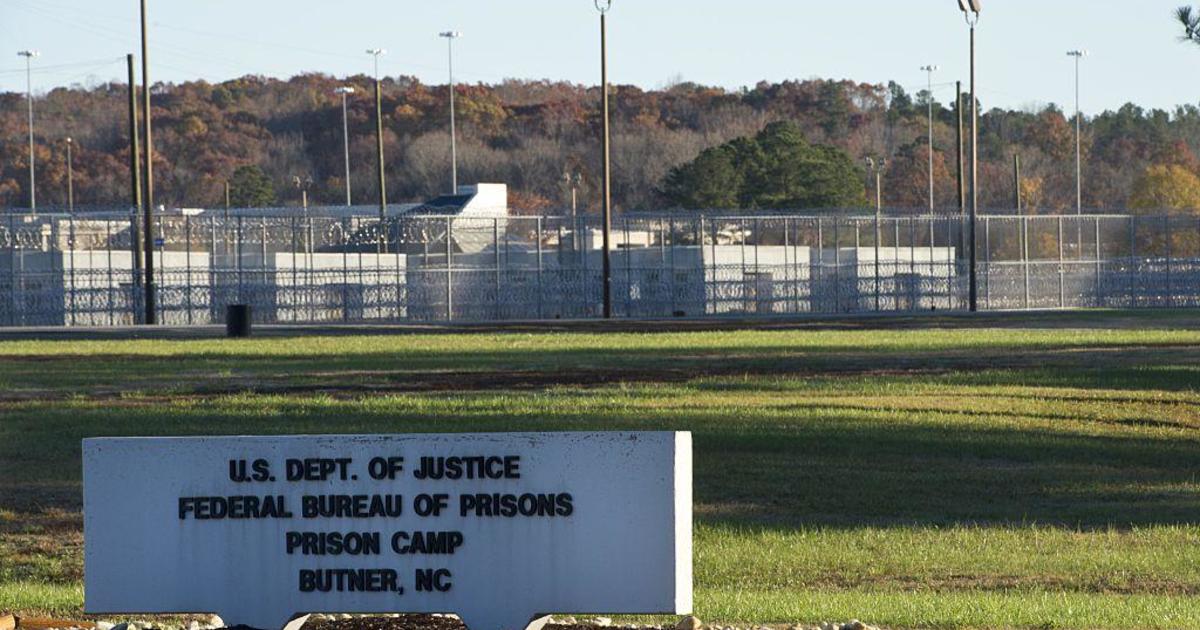

Spiwak, 73, was serving a 15-year sentence on child pornography charges at the low-security federal prison in Butner, North Carolina, one of the facilities most affected by the virus. Spiwak and 15 other people died in Butner after hiring COVID-19, the office said, more than any other federal prison in the country.

Jones, who was close to her father, had made the decision to distance herself from him about a year ago to resolve her own trauma related to the conduct Spiwak had been convicted of in the 1980s. Her sister still communicated with him regularly. He was the one who received the phone call from a prison chaplain, informing him that his father had died.

“I had to take a step back,” Jones explained. “For anyone who has lost someone close, particularly so suddenly and without warning, you don’t know how long you don’t have until you don’t have it.”

The chaplain called less than two days after Jones received the phone call, saying it was the only official communication his family had with the prison about his father’s illness. Looking back, she is grateful for that brief phone call with her father because, without her, she and her family would never have known that her father was ill. It was the first time they had spoken in months: “We couldn’t even say ‘I love you’ to each other.”

Many advocates have lobbied for an expanded use of compassionate release or for the office to extend home confinement privileges to more of the prison population. By reducing the number of inmates inside, they argue that prisons could use social distancing practices and limit exposure.

Congressman Bobby Rush, a Democrat from Illinois, has expressed concern about the inability to practice social distancing in the prison system. “I think it is reprehensible, it is unfathomable,” Rush said in response to the 100 inmate deaths. “It doesn’t make sense. Why are we playing Russian roulette with older, non-violent prisoners who don’t pose a threat to society?”

In May, when the House passed the Heroes Act, it included the House-passed Rush Prison Telephone Justice Act, which would prohibit prisons from making commissions on inmate phone calls, making it easier for them to stay on contact with loved ones during the pandemic.

For Rush, it’s personal. In 1972, the former member of the Black Panther movement was jailed for six months for what he calls a false weapons charge.

“I believe that the Bureau of Prisons and the judicial system should recognize this critical problem and should act immediately, if not sooner, to eliminate this problem and release these elderly prisoners,” he said.

In March, Attorney General William Barr instructed the office to expand the use of home confinement among older inmates with underlying conditions in response to the pandemic. Since then, they reported that more than 7,000 inmates had been released from the program.

That number is not enough, said Sharon Dolovich, a law professor and director of the behind-the-scenes data project UCV COVID-19.

“These are deaths that did not have to happen,” said Dolovich. “There were clear steps that the BOP had available for many months that would have reduced the risk inside, and they have shown a total unwillingness to take those steps. As a result, people are dying.”

Dolovich and his team of researchers. track virus cases within the country’s state and federal correctional facilities. As of Monday, more than 82,000 inmates have been infected and 735 have died, according to the project. He said there were more than 19,300 cases among staff and 56 deaths.

The office reports that only one federal prison employee, Charlynn Phillips, who worked at Butner, died in June after contracting the virus.

The office, however, does not count the death of another staff member, Robin Grubbs, who passed away in April. Grubbs, a 39-year-old case manager at the United States Penitentiary in Atlanta, posthumously tested positive for the virus. However, his cause of death was never determined to be due to COVID-19 because an autopsy was not completed.

Grubbs had been promoted just a month before her death, a role that would have pulled her out of an area that brought her closer to inmates who had been exposed to the virus. She was an army veteran and worked for the prison for over a decade.

.