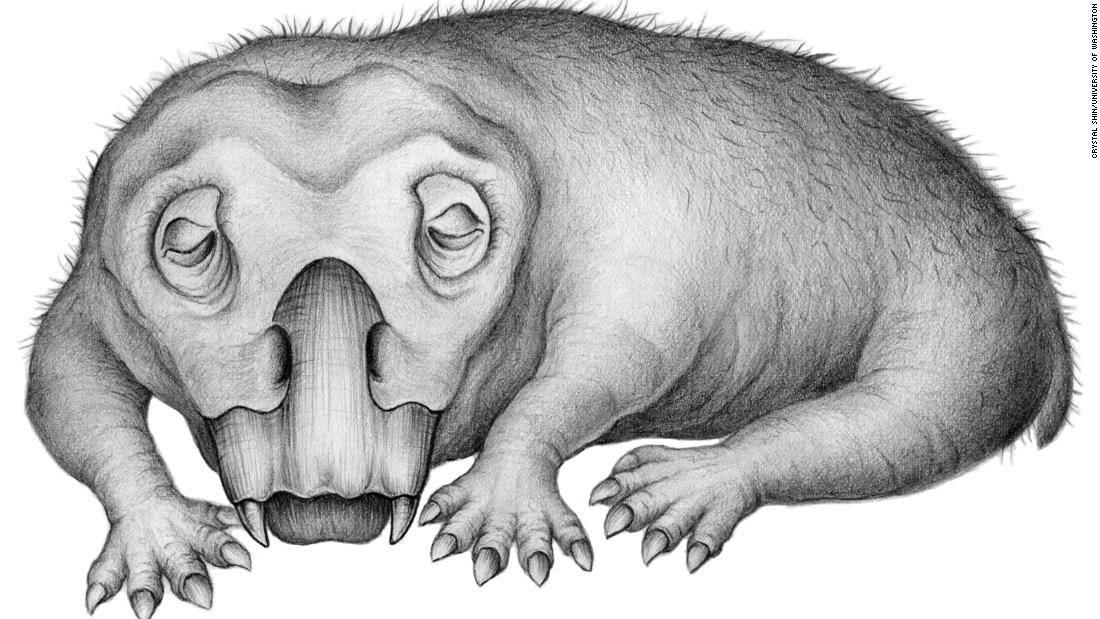

Listrosaurus is a mammal-like creature of the early Triassic period that roamed in modern days such as India, South Africa and Antarctica 250 million years ago. It has a tusk like an elephant and a beak like a tortoise, and it was almost the size of a pig.

Scientists at Washington University in Washington have used the remains of animal tusks to test the differences in stress between species living in a polar climate like Africa and in warm people. This tusk is main because it can measure the life span of an animal like rings on a tree.

They found prolonged stress compatibility with animals that experienced torpedoes, or rested for long periods of time, such as hibernation, and are the oldest known torpedoes in fossil records.

“To see the specific signs of stress and strain brought about by hibernation, you need to look at something that can become fossilized during an animal’s life and is constantly increasing,” said Christian Sidor, a co-author of a biology professor at the University of Washington. “A lot of animals don’t have that, but luckily Listrosource did.”

Scientists also believe that it could explain why the animal survived mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, which destroyed 70% of the vertebrate species on land.

The researchers said they could not prove conclusively that Listrosaurus went into true hibernation as we know it, but the stress could be caused by another type of short-term torpedo.

“What we’ve observed in the Antarctic Listrosaurus Tusk fits the pattern of small metabolic ‘reactivation events’ during periods of stress, similar to what we see in warm-blooded hibernators today,” Whitney said.

.