[ad_1]

Medscape asked top experts for input on the most pressing scientific questions about COVID-19. Please check back frequently for more COVID-19 data analysis and visit Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center for full coverage.

Muge Cevik, MD, MSc

Over the past 6 months, we have learned a lot about how SARS-CoV-2 spreads. Let’s review what the evidence so far tells us about the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, high-risk activities and settings, according to a recent article my colleagues and I published in Infectious Clinical Diseases.

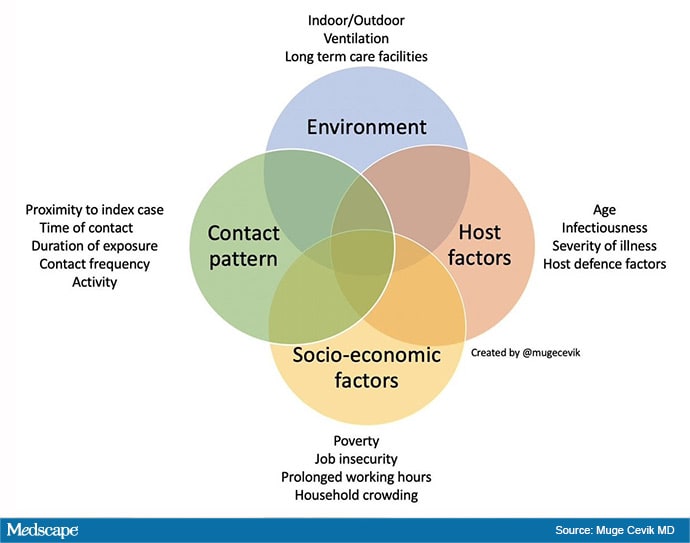

The risk of transmission is complex and multidimensional. It depends on many factors, including contact pattern (ie duration, proximity, activity), individual factors, environmental factors (ie exterior, interior), and socio-economic factors (ie crowded housing, job insecurity).

As I described in a recent Twitter thread, let’s take a look at each of these.

Contact pattern. We now know that sustained close contact drives most infections and clusters. For example, contacts and gatherings of family and close friends present a higher risk of transmission than shopping at the market or brief community gatherings.

Even within the same household, frequent daily contact with the index case, such as dining in close proximity or spouses and partners sharing the same sleeping space, has been associated with an increased risk of transmission.

Participating in group activities, such as dining together or playing board games, has been found to pose a high risk of transmission for non-home contacts, as do gatherings that tend to accumulate large groups, such as weddings and cocktail parties. birthday. Other examples include pub gatherings, church services, and nearby business meetings. These findings suggest that group activities pose a higher risk of transmission. Risk increases with longer and more frequent exposure, close proximity, number of contacts, and group activities, especially meals.

Individual factors. Individual infectivity factors vary widely. Many people do not infect anyone or infect only one person. A large number of secondary cases are caused by a small number of infected people. Although many factors are at play, individual variation in infectivity plays an important role.

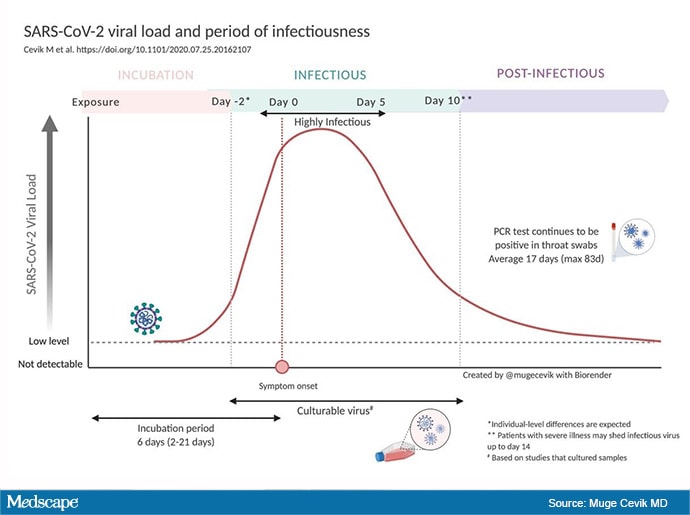

When we look at viral load dynamics and contact tracing studies, those who are infected are highly infectious for a short period, probably 1-2 days before and 5 days after the onset of symptoms. So far, no transmission has been documented after the first week of symptom onset.

While patients without symptoms can transmit the virus to others, emerging evidence, detailed in two publications, a preprint and a published article, suggests that asymptomatic index cases are transmitted to fewer secondary cases. Attack rates (the number of people who get sick of the number of people who are at risk from exposure) are highly correlated with the severity of symptoms.

Transmission is also affected by other host factors, including the host’s defense mechanisms and age. For example, given the same exposure, susceptibility to infection increases with age. It is higher in those over the age of 60 compared to younger or middle-aged adults.

Environmental factors. The impact of the contact pattern also depends on the scene of the encounter. Contact tracing studies suggest that indoor environments are associated with a transmission risk that is 20 times greater than outdoor environments.

Prolonged indoor contact in a crowded and poorly ventilated environment substantially increases the risk of transmission. But lowering occupancy and improving ventilation by opening windows and doors can reduce risk.

The largest outbreaks around the world have been reported in long-term care facilities (such as nursing homes), homeless shelters, prisons, and meat-packing plants where many people spend several hours working, living together, and sharing spaces. common.

The largest clusters of cases observed in the United States have been associated with prisons or jails. At Germany’s largest meatpacking plant, while the common potential point of contact was the workplace, the risk was greatest for those living in a single shared apartment or dormitory, or on a shared ride.

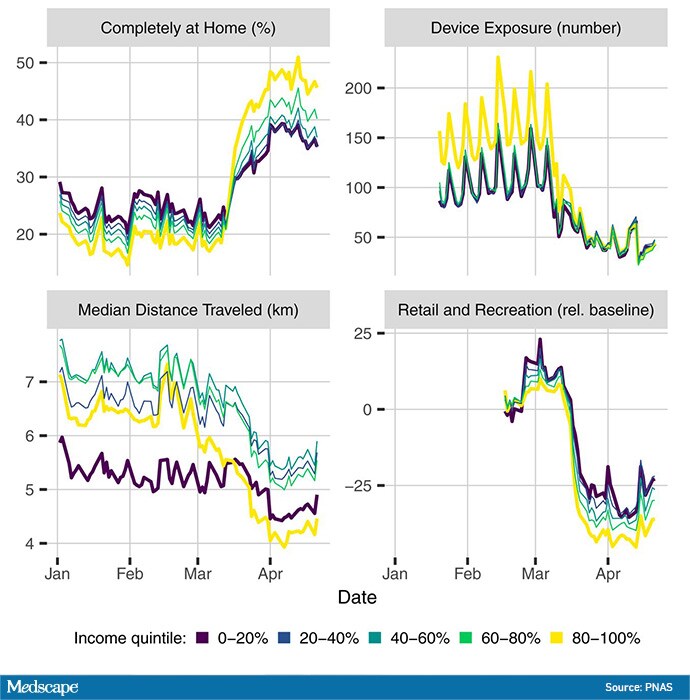

Socioeconomic factors. Global figures suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic is strongly conditioned by structural inequalities, adverse living and working conditions, and structural racism that generate domestic and occupational risks.

People in lower-wage occupations are often classified as essential workers who must work outside the home and can travel to work by public transportation. These occupations often involve more social contact and risk of exposure due to long working hours and job insecurity.

Households in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas are more likely to be overcrowded, increasing the risk of transmission within the household. These disparities also shape the strong geographic heterogeneities observed in the burden of cases and deaths.

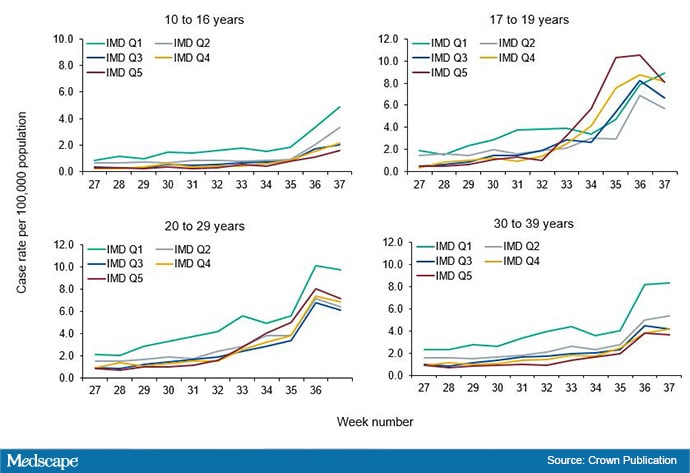

The Public Health England surveillance report shows that while the number of infections in England is increasing mainly in the 20-29 and 30-39 age groups, SARS-CoV-2 is spreading more in areas very disadvantaged where people are employed in low-paying jobs and I can’t afford to isolate myself.

In Madrid, 37 neighborhoods are registering the highest incidence, four times the average of the rest of Spain. These areas have common factors: they are poorer, denser and have a large immigrant population.

Previous research suggests that although social distancing during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic succeeded in reducing infections, the effect was more pronounced in households with greater socioeconomic advantage. Similar findings are emerging for COVID-19.

COVID-19 could now be endemic in some parts of England combining severe deprivation; bad housing; and large black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. The national blockade had little effect in reducing the level of infections in these parts of northern England.

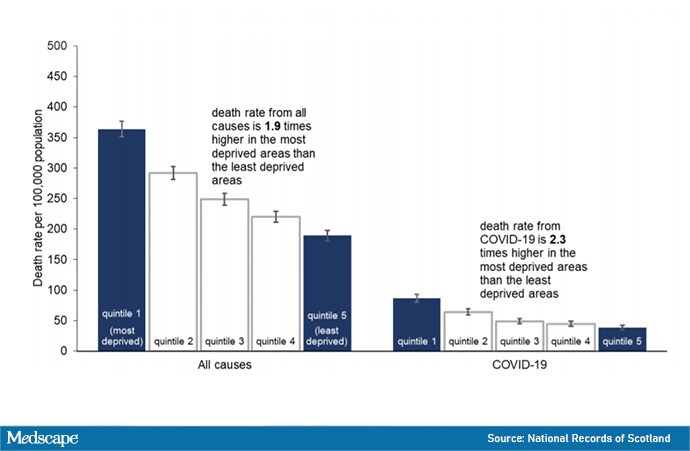

A real overlap of causes of mortality and deprivation can be seen in the figure below. Data from Scotland show that the age-standardized rate of COVID-19-related deaths in the most disadvantaged quintile was more than double (2.3 times higher) than that of the least disadvantaged quintile.

In summary, the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on households living in poverty, and the racial and ethnic disparities observed in many countries, emphasize the need to urgently update our definition of “vulnerable” populations for COVID-19 and address these. inequities.

These include income and social protection and support to ensure that low-wage, non-salaried and contract workers, who are generally not guaranteed a minimum number of working hours, can afford to follow isolation and quarantine recommendations. Providing protective equipment for workplaces and community settings is also critical.

The peak in viral load that occurs early in the disease course indicates that prevention of continued transmission requires immediate self-isolation with the onset of symptoms (for a minimum of 5 days). Patient education should prioritize isolation practices and policies should include supported isolation.

There are many things that can be done within families to decrease transmission. We need to provide clear instructions and means of support so that people with positive symptoms or tests and their contacts can isolate themselves.

Policy-makers and health experts can help the public differentiate between lower-risk and higher-risk activities, and environmental and public health messages could convey a spectrum of risk to the public to support participation in alternatives for an interaction. Safer.

Without clear public health communication about risk, people can become obsessed with unlikely sources of transmission (outdoor activities) while underestimating higher-risk settings, such as family and friends gatherings and indoor settings. Therefore, the advice must be clear and consistent with the transmission dynamics. Avoid closed environments with many people and with little ventilation. Spend more time outdoors. Keep your distance (more is better, but 6 feet is not a panacea). Improve ventilation: Open windows and doors. Wear a mask indoors. Handwashing.

Some high-risk settings, such as nursing homes, prisons, shelters, and meatpacking plants, will require public health strategies tailored to those specific settings. This should include personal protective equipment and routine tests to identify infected people early in the course of the disease.

While modeling studies, computer simulations, and droplet aerodynamics could contribute to our understanding of transmission, contact tracing studies provide real-life transmission dynamics and individual and structural factors associated with transmission of the SARS-CoV-2, which are essential in shaping our audience. health plans, mitigate over-spreading events, and control the current pandemic.

Muge Cevik, MD, MSc, is a physician and researcher in infectious diseases and medical virology at the University of St. Andrews. His research interests focus on HIV, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, emerging infections, and tropical infections in low- and middle-income countries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to working on the front lines of the response, he provided scientific input to Scotland’s chief medical officer, and provides expert input to the WHO Epidemic Information Network on the COVID-related infodemic. 19. .

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube

[ad_2]