[ad_1]

The annual flu season threatens to make the COVID-19 pandemic doubly deadly, but I believe this is not inevitable.

There are two commonly given vaccines, the pneumococcal vaccine and the Hib vaccine, that protect against bacterial pneumonias. These bacteria complicate both influenza and COVID-19, and often lead to death. My examination of disease trends and vaccination rates leads me to believe that the wider use of the pneumococcal and Hib vaccines could protect against the worst effects of a COVID-19 disease.

I am an immunologist and physiologist interested in the effects of combined infections on immunity. I have come to my knowledge by juxtaposing two seemingly unrelated puzzles: Babies and children contract SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, but they are very rarely hospitalized or die; and the number of cases and death rates from COVID-19 began to vary greatly from nation to nation and city to city even before the closures began. I wondered why.

One night I woke up with a possible answer: vaccination rates. Most children, from the age of two months, are vaccinated against many diseases; adults less. Additionally, infant and adult vaccination rates vary widely around the world. Could differences in vaccination rates against one or more diseases explain differences in COVID-19 risks? As someone who had previously investigated other pandemics such as the 1918-19 Great Flu Pandemic and AIDS, and who had worked with vaccines, I had solid experience in tracking down the relevant data to test my hypothesis.

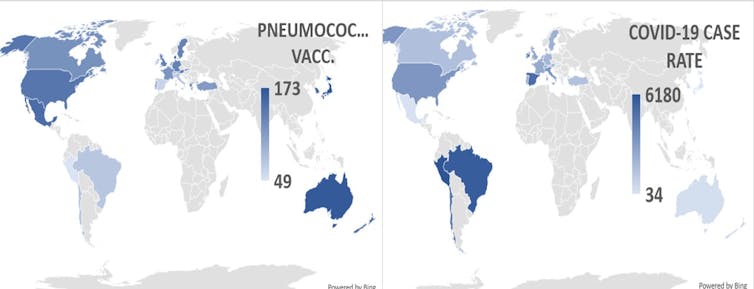

Pneumococcal vaccination rates correlate with fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths

I collected national and local data on vaccination rates against influenza, polio, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP), tuberculosis (BCG), pneumococci, and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib ). I correlated them with the COVID-19 case rates and death rates for 24 countries that had experienced their COVID-19 outbreaks at around the same time. I controlled for factors such as the percentage of the population that was obese, diabetic, or elderly.

I found that only pneumococcal vaccines provided statistically significant protection against COVID-19. Countries like Spain, Italy, Belgium, Brazil, Peru, and Chile that have the highest COVID-19 rates per million have the lowest pneumococcal vaccination rates among infants and adults. The nations with the lowest rates of COVID-19 – Japan, Korea, Denmark, Australia, and New Zealand – have the highest rates of pneumococcal vaccination among infants and adults.

A recent preprint study (not yet peer-reviewed) by Mayo Clinic researchers has also reported very strong associations between pneumococcal vaccination and protection against COVID-19. This is especially true among minority patients who are most affected by the coronavirus pandemic. The report also suggests that other vaccines or vaccine combinations, such as Hib and MMR, may also provide protection.

These results are important because in the US, childhood pneumococcal vaccination, which protects against steotococci pneumonia bacteria: varies by state from 74% to 92%. Although the CDC recommends that all adults ages 18 to 64 in high-risk groups for COVID-19 and all adults 65 and older be vaccinated against pneumococcus, only 23% of high-risk adults and 64% of those over 65 do so then.

Similarly, although the CDC recommends that all babies and some high-risk adults get vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), only 80.7% of children in the US and a handful of immunologically compromised adults have been. Vaccination rates for pneumococcus and Hib are significantly lower in minority populations in the US and in countries that have been more affected by COVID-19 than the US.

Based on these data, I advocate for universal pneumococcal and Hib vaccination among children, at-risk adults, and all adults over the age of 65 to prevent severe COVID-19 disease.

How the Pneumococcal Vaccine Protects Against COVID-19

Protecting against severe COVID-19 disease by pneumococcal and Hib vaccines makes sense for several reasons. First, recent studies reveal that the majority of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, and in some studies nearly all, are infected with streptococci, which cause pneumococcal pneumonia, Hib, or other bacteria that cause pneumonia. Pneumococcal and Hib vaccines should protect coronavirus patients from these infections and thus significantly reduce the risk of severe pneumonia.

I also discovered that pneumococcal, Hib, and possibly rubella vaccines can confer specific protection against the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 through “molecular mimicry.”

Molecular mimicry occurs when the immune system thinks that one microbe looks like another. In this case, the proteins found in pneumococcal vaccines and, to a lesser extent, those found in Hib and rubella vaccines, also resemble several proteins produced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Two of these proteins found in pneumococcal vaccines mimic the membrane and spike proteins that allow the virus to infect cells. This suggests that pneumococcal vaccination can prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Two other mimics are the nucleoprotein and replicase that control virus replication. These proteins are produced after a viral infection, in which case pneumococcal vaccination can control, but not prevent, the replication of SARS-CoV-2.

Either way, these vaccines can provide indirect protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection that we can implement right now, even before we have a specific virus vaccine. Such protection may not be complete. People can still suffer from a weakened version of COVID-19 but, like most babies and children, they must be protected against the worst effects of infection.

While the specific protection these other vaccines confer against COVID-19 has yet to be tested in a clinical trial, I advocate for a broader implementation of pneumococcal and Hib vaccination for an additional well-validated reason.

Pneumococcal and Hib pneumonia, both caused by bacteria, are the leading causes of death after viral influenza. The influenza virus rarely causes death directly. Very often, the virus makes the lungs more susceptible to bacterial pneumonias, which are deadly. Dozens of studies around the world have shown that increased rates of pneumococcal and Hib vaccination dramatically reduce influenza-related pneumonia.

Similar studies show that the price of using these vaccines outweighs the savings from lower rates of influenza-related hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and deaths. In the context of COVID-19, reducing rates of influenza-related hospitalizations and ICU admissions would free up resources to combat coronavirus, regardless of any effect these vaccines may have on SARS-CoV-2 itself. In my opinion, that’s a winning scenario.

In short, we don’t need to wait for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine to slow down COVID-19.

I believe that we can and must act now by fighting the coronavirus with all the tools at our disposal, including vaccines against influenza, Hib, pneumococcus and perhaps rubella.

Preventing the pneumococcal and Hib complications of influenza and COVID-19, and perhaps indirect vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 itself, helps everyone. Giving people these well-proven and available pneumococcal and Hib vaccines will save money by freeing up hospital and ICU beds. It will also improve public health by reducing the spread of multiple infections and boost the economy by fostering a healthier population.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert Root-Bernstein

Robert Root-Bernstein is a professor of physiology at Michigan State University. His BA and Ph.D. are from Princeton University. He did his postdoctoral research with Jonas Salk, MD, at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. In 1981, he was awarded a MacArthur Scholarship, commonly known as a “Genius Scholarship.” His research focuses on autoimmune diseases, drug development, the origins of cell control systems, and science-arts interactions. He has also researched and advised on creativity for over fifteen years. Among other books, he is the author of Sparks of Genius: The Thirteen Thinking Tools of the World’s Most Creative People; Honey, mud, worms and other medical wonders; Discover: Inventing and Solving Problems at the Frontiers of Scientific Knowledge and Rethinking AIDS: The Tragic Cost of Premature Consensus.

This article is courtesy of The Conversation.