[ad_1]

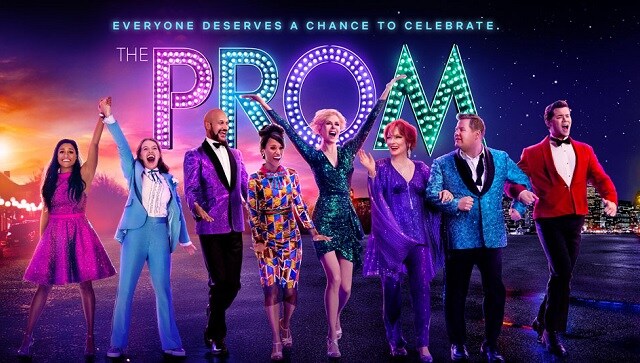

Ryan Murphy’s prom, with its crafty mix of nostalgia and idealism, old-fashioned conservatism and new-age liberalism, will hit the mark for some, even if his vision of American unity is hard to recognize in 2020.

At the beginning of Ryan Murphy The prom, a Broadway fan begins reading the reviews of a newly opened show about Eleanor Roosevelt, “Eleanor!” The whole band is here, including the self-worshiping stars Dee Dee Allen (Meryl Streep) and Barry Glickman (James Corden). The drinks and laughter flow, and everyone is as lit up as their dazzling outfits. And then the flack starts reading the notice The New York Times (hiss, boo). “This is not a review you want when you have shitty advance sales,” he bleated. “This is going to shut us down.”

In your review of The prom on Broadway, my Times Colleague Jesse Green amusingly assured readers that this would not happen, calling it “a shout of joy.” It won’t happen with the movie, which is based on the show, for other reasons. The prom starts streaming on Netflix on Friday, which means the amount of cheering or teasing won’t matter. On Netflix, the movie will sit alongside thousands of other titles, subject only to mysterious algorithms and protected from both critics and the box office.

His crafty mix of nostalgia and idealism, old-fashioned conservatism and new-age liberalism will hit the mark for some, even if his vision of American unity is hard to recognize right now.

In its broad lines, the story, a showbiz lark married to a moral tale about the triumph of a teenage lesbian, seems unchanged. Branded unsavory narcissists (who can’t even make it big), Dee Dee and Barry decide to rehabilitate their tainted reputations with celebrity activism. With their second overripe bananas, the malicious Angie Dickinson and Trent Oliver (Nicole Kidman and Andrew Rannells), travel to an Indiana town, intending to take on (uninvited) the cause of the heroine, Emma (Jo Ellen Pellman) , a high school student who has been banned from taking his girlfriend to prom.

.jpg)

A still from The Prom

The theme and story emerge when Dee Dee et al they descend on the city, waving banners and shouting outrage. “We are here from New York City and we are going to save them,” Barry announces to Emma, who is immersed in a gathering full of parents and other students. This joke is soon repeated, as it often happens in this movie, where each rose is golden and each laugh squeezed until dry. “Who are you?” asks the mother (a battered Kerry Washington) leading the homophobic prosecution. “We are Broadway liberals,” says Trent, assuring that the New York team will fall on its smug face as it secures its own redemption.

The message of tolerance in The prom it’s sincere, no matter how satirical. And it’s easy to imagine that on stage everything turned out lovely (as a friend insisted), a quality not found in Murphy’s paint box. (The charm of his television series Joy It grew out of the youth of its cast and the musical genre itself.) Murphy likes to go big and slightly crazy, and his aesthetic is best described as Showbiz Expressionism – it’s ostentatious and seemingly excessive without being threatening. In contrast to, say, the shocks of John Waters, for whom lack of taste is a rebellion (aesthetic, political), Murphy’s excesses are vulgar blows of good taste rather than value.

The story unfolds with histrionics and homilies, jazzy hands and sparkling fingers, overly busy camera work, and off-hook lungs. (Matthew Sklar wrote the music and Chad Beguelin wrote the lyrics and, with Bob Martin, the script.) Some of the songs are daring (“let’s help that little lesbian / whether she likes it or not”); others are as serious as a daily statement (“life is not a dress rehearsal”). Together, they create a parallel narrative that makes dialogue superfluous. “If you’re not straight,” Emma sings at the beginning, “then guess what will surely hit the fan.” Later, he sings “no one out there gets to define / the life I’m supposed to lead.”

Meryl Streep at the prom

Pellman doesn’t seem remotely like a teenager, but her brooding sweetness is inviting and has a quiet quality that creates a much-needed oasis amid Murphy’s insistent din. It helps that, in contrast to his famous co-stars, he hasn’t been ordered to exaggerate every note, be it musical or emotional. With her open face and pretty soprano, she turns her character into a recognizable teenager, and lets you see, and feel, Emma’s longing, her pain, and the belief that something better, more soul-enriching, awaits more. beyond the prejudices and provincialism of his city. . Like Dorothy and many others, Emma dreams of her place on the rainbow.

He succeeds, with the help of his soon-to-be humble and ultimately victorious New York aides (and the warm presence of Keegan-Michael Key as director).

How all of this happens is as predictable as expected, except, in 2020, it’s also more fantastic than The Wizard of Oz at its most trippiez.

Here, all fans need to accept Emma and LGBTQ rights is for Trent to call them hypocrites who should, in a sublimely narcissistic move, be more like his fabulous and righteous interlopers. In other words, if the haters opened their hard little hearts, everything would be fine. You don’t have to be a cynic to know it’s silly. You just need to be an American.

Manohla Dargis c.2020 The New York Times Company

All Twitter images

Find the latest and upcoming tech gadgets online at Tech2 Gadgets. Get tech news, gadget reviews and ratings. Popular devices including laptop, tablet and mobile specifications, features, pricing and comparison.

[ad_2]