[ad_1]

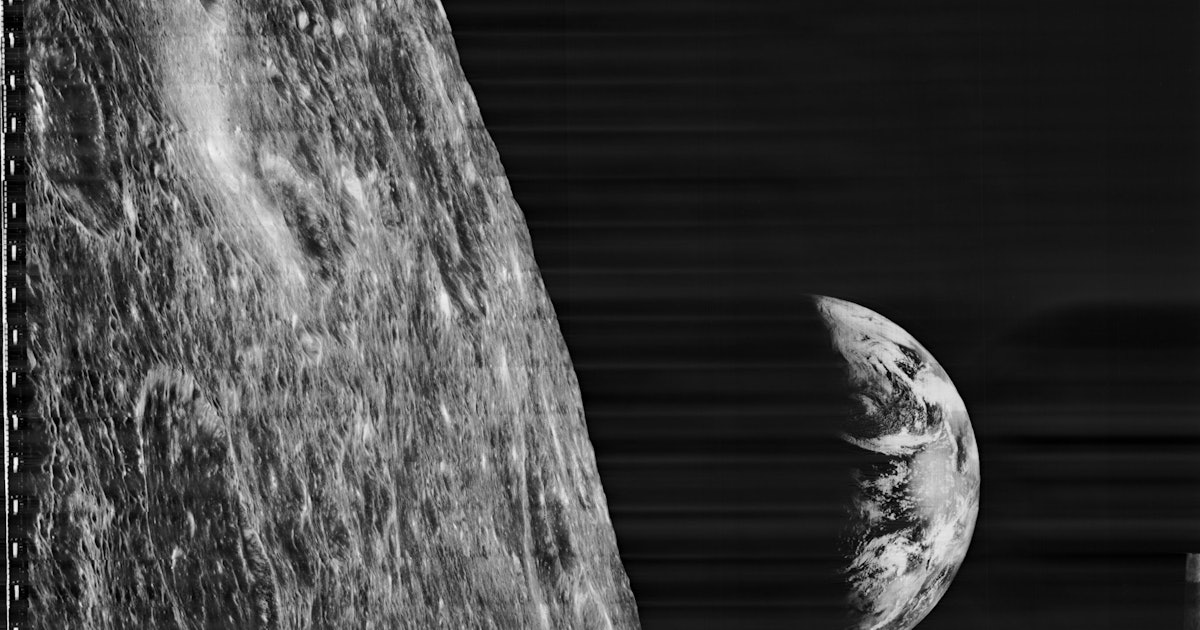

About 4 billion years ago, a massive object the size of Mars collided with a young developing Earth.

The collision threw vaporized particles from Earth into space, which were then pulled together by gravity to form the Moon.

This is just a theory of how the Moon was formed. Since then, our planet and its only natural satellite have been inseparable ever since. A new study suggests that the relationship between Earth and the Moon is even deeper, and that the Moon may have protected Earth from losing its entire atmosphere, allowing life to flourish on our planet.

The findings are detailed in a study published this week in the journal Scientific advances.

When it first formed, the Moon was three times closer to Earth than it is today, some 80,000 miles away. In context, it is now 378,000 miles from Earth.

Lunar samples returned by astronauts during the Apollo missions revealed that the Moon once had a magnetic field like Earth’s, which acted as a shield against electrical charges.

In the new study, the scientists simulated how the Earth’s and the Moon’s magnetic fields would have interacted about 4 billion years ago, when the pair was much closer to each other. What they found suggests that the Moon was not simply Earth’s close companion, it was the protector of our planet.

“The Moon appears to have presented a substantial protective barrier against the solar wind for Earth, which was critical to Earth’s ability to maintain its atmosphere during this time,” said Jim Green, NASA’s chief scientist and lead author of the new study, in a statement accompanying the investigation.

The magnetosphere of the Moon and Earth, the region of space that surrounds an object where charged particles are affected by that object’s magnetic field, would have become magnetically connected in each of their polar regions.

As a result, the charged particles emitted by the Sun as a solar wind would not have been able to penetrate the pair’s shared magnetic field.

Without the Moon, the Earth may not have been able to withstand the powerful radiation emissions from the Sun, which constantly bombarded the young planet at the time. If these emissions had passed through the shield, it would have made it impossible for life to flourish on our planet.

However, over time, the Moon slowly lost its magnetic field and atmosphere.

Understanding the effect of the Moon on Earth’s habitability helps scientists in their search for signs of life on other worlds. This study suggests that an exoplanet’s moon could affect the potential for life on that world.

The scientists behind this study plan to further validate their findings using data collected during NASA’s upcoming Artemis mission to the Moon. One of the mission’s goals is to return the first lunar samples from the Moon’s South Pole, where the Moon and Earth’s magnetic field are believed to be most strongly connected.

“We hope to follow up on these findings when NASA sends astronauts to the Moon through the Artemis program,” Green said.

“Significant samples from these permanently shadowed regions will be critical for us to unravel this early evolution of Earth’s volatiles, testing the assumptions of our model,” he noted.

Abstract: Apollo lunar samples reveal that the Moon generated its own global magnetosphere, which lasted between ~ 4.25 and ~ 2.5 billion years (Ga). At the lunar peak of magnetic intensity (4 Ga ago), the Moon was volcanically active, probably generating a very thin atmosphere, and is believed to be at a geocentric distance of ~ 18 Earth radii (Rme). Solar storms destroy a planet’s atmosphere over time, and only a strong magnetosphere could provide maximum protection. We present a simplified model of a confined magnetic dipole field within a paraboloidal shaped magnetopause to show how the expected Earth-Moon coupled magnetospheres provide a substantial buffer from the expected strong solar wind, reducing the atmospheric loss from Earth to space.