[ad_1]

Last week, the United States, Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom signed the relatively concise Artemis Accords, a rather vague set of acknowledgments about the future of space exploration. NASA has reportedly been working for some time, bilaterally with each of the signatories, to nail down the details (or lack thereof) of the agreement. While Russia, which has been a long-time American partner in space exploration, has yet to sign it, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine hopes it will soon.

Artemis is the goddess of the Moon in Greek mythology, and the deals seem interested, at least initially, in the upcoming US Artemis Lunar Exploration Program, with a similar name, which will resume manned missions to the moon for 2024. In addition to its immediate focus on the moon, the agreement allegedly further consolidates the principles agreed to in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and its progeny. Therefore, the Accords, despite their wide, if superficial range of topics, appear to have a singular purpose: the signing of the bilateral agreements, which is a prerequisite for their inclusion in those NASA manned lunar missions, is intended to create legal support for mining the moon and other celestial bodies.

Eight countries sign agreements on the future of space exploration. Photo: Getty Images

Eight countries sign agreements on the future of space exploration. Photo: Getty Images While it is ironic that on the eve of the anniversary of 20 continuous years of human residence in space on the aptly named International Space Station, the United States seems to have mostly gone alone in spearheading these bilateral agreements, it is understandable why that choice was made. NASA administrators have essentially admitted that while the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) is probably the best forum to determine what we can and cannot do in space in relation to things like lunar mining and resource extraction, it doesn’t exist.It’s time to wait for the consensus-driven body to come to a determination, especially if diplomacy requires a below-average determination from the perspective of the United States, which sees the extraction of Moon resources as a necessity for future lunar bases.

While space mining issues are relatively new to space law, much of the agreed text in the Accords reiterates long-standing customary practice, if not absolute international law, as detailed in the first four of the five treaties. space travel, and as has been practiced by most nations with space travel for the last half century. These reiterations include, for example, the obligation to register relevant space objects, as well as a reaffirmation of the obligation to assist personnel in space in distress.

In particular, in the text of the new agreement, the term “astronaut” from previous space treaties was replaced by the more general term “personal”. It is possible that this was intentional in light of the emerging reality that future space travel will include civilian tourists and other unconventional passengers who are not astronauts in the conventional sense.

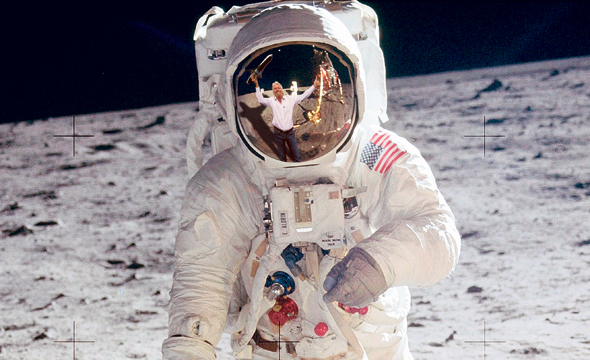

Despite that particular appreciation that billionaires like Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic will play an increasingly important role in space travel, there are few other acknowledgments, if any, that much of space exploration beyond flight Branson’s suborbital tour will also be private. in nature.

Richard Branson’s reflections on an astronaut’s helmet. Photo: Getty Images

Richard Branson’s reflections on an astronaut’s helmet. Photo: Getty Images Indeed, the only resounding recognition of the increasingly central role of private space actors appears to be one small size of a data sharing exemption for those private actors. That’s. It is not even clear if the lack of exclusions of other private actors in the rest of the document implies that there are none, and if the private sector is equally bound to them or is simply not part of the agreement. The latter seems more likely.

An especially interesting aspect of the treaty is the obligation to preserve the oldest landing sites as a shared heritage of humanity, as if the bags full of astronaut excrement that were unceremoniously thrown on the moon had some kind of sacred value. But this has been the goal of various non-governmental organizations for some time, so it is not surprising that it eventually became a multinational document. Similarly, regarding the protection of the space environment, the last two substantive paragraphs, although brief and vague, cause the parties to agree to address one of the most important problems in outer space: orbital debris, also known as space debris. Clearly, the Accords distinguish the space junk that we left on the moon, and is now protected under the Accords, from the orbiting space junk that needs to be taken out with the junk.

The most surprising part of the Accords, however, was the not-too-subtle burial of the lead. At the heart of the document, the parties finally agree on the main purpose of the aforementioned document: that the extraction of celestial bodies is legal under international law, and that countries have the right to create ‘security zones’ apparently similar to economic zones. exclusive of the sea that protect private and national interests far from the coast.

The controversial topic of space mining has been around (like a lunar astronaut in one-eighth of Earth’s gravity) for some time. The Treaties on outer space are somewhat ambiguous on the subject. They clearly state that space is “the province of all humanity” and that national ownership is discouraged, but it is unclear if that means that no resources can be extracted at all. For example, the Antarctic Treaty System, which similarly regulates Antarctica almost as remote, had to specifically specify the ban on mining, as it was not considered clear enough in the other treaty texts.

Another inhospitable place, the deep sea, is also considered a universal resource and, like Antarctica, we are allowed to extract fish from the deep sea. Furthermore, deep water laws allow for mineral extraction under international law, although none have yet been mined. To some extent, the United States is trying to create the same understanding about space with the support of a handful of other international actors.

At least two countries, the US, in 2015 under President Obama, and Luxembourg, in 2017, and perhaps more recently the UAE, already have laws providing for the extraction of minerals from extraterrestrial bodies. The signing of these new agreements simply further concretizes this American understanding of international space law in the Artemis Accords. This American understanding of the law could become established law, especially if other nations do not oppose NASA’s mining activities on the Moon.

To get an early start, in September, NASA transparently offered to buy lunar regolith mined from private companies in an effort clearly designed to set a precedent to further bolster its pro-mining position in international law. NASA hopes no one will make an international fuss when that happens.

Perhaps this lucrative business opportunity can help fund Israel’s next photo of the moon and provide much-needed financial support for Israel’s growing civilian space industry.

[ad_2]