[ad_1]

Abigail banerjiFebruary 25, 2021 7:47:24 PM IS

With ‘Ms Rona’, better known as the coronavirus, celebrating her first birthday since she came into our lives, terms such as pandemic, PPE, antibodies, antigens, etc. have grown in demand and popularity, it is now part of our daily vocabulary. . Many of us can now understand the complex process of developing a vaccine, the clinical trials it goes through, and the regulatory approvals it would need before implementation. We have lived and learned.

With the SARS-CoV-2 virus rapidly ‘mutating’, new ‘variants’ of the virus have emerged in many parts of the world. In the pre-COVID-19 era, we could have used this new piece of information to impress friends or family over dinner or cocktail parties. But let’s be honest, the very variants in question are unlikely to allow that to happen anytime soon.

So, let’s dig deeper and understand the basics …

What is a virus?

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we had vaguely heard about viruses that caused diseases like Ebola in Guinea and Congo, swine flu or bird flu in India and Russia, AIDS, etc. We now know that the SARS-CoV-2 virus causes COVID -19 illness.

According to a report by American scientist, the scientific community for many years has debated the definition of viruses; first as a poison, then as a way of life, and then as a biological chemical.

Today, viruses are considered to be somewhere between living and non-living things.

TO virus It is made up of a nucleus of genetic material (DNA or RNA) surrounded by a protective layer of protein. They can adhere to host cells and use the host cell’s machinery to multiply their genetic material. Once this replication process is complete, the virus leaves the host by sprouting or exiting the cell, destroying it in the process.

Viruses cannot replicate on their own, but once they attach to a host cell, they can thrive and affect the behavior of the host cell in a way that harms the host and benefits the virus.

What is a strain?

A strain, according to a report by The conversation, is a variant that is built differently, displays different physical properties, and behaves differently from its parent virus. These differences in behavior can be subtle or obvious.

Coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), are dotted with protein “spikes” that bind to receptors on the cells of their victims. SARS-CoV-2 is now one of a handful of other known strains in the coronavirus family, including the SARS and MERS viruses.

Experts believe that the term strain is often used incorrectly.

“There is a strain of coronavirus. That is SARS-CoV-2. That is the single strain, and there are variants of that strain.” The independent he quoted Professor Tom Connor of the Cardiff University School of Biosciences as saying.

What is a mutation?

A virus is made up of a sequence of DNA or RNA, which are basically a string of nucleotide letters that encode genes in all living things. Any change in these letters is called a mutation and occurs when the sequence of a virus replicates. Mutations occur very randomly in a virus, a fact that could work for or against us in a pandemic scenario. A mutation can be beneficial to the virus and make it stronger, or it can be harmful and reduce its virulence.

SARS-COV-2, unlike the influenza virus, has a protein known as a correcting enzyme. The enzyme is similar to what a text editor does in a newspaper, that is, to check for spelling errors on a page. This enzyme will make corrections, based on the sequence of the source virus. So if there was any change that occurred due to random mutation, it will try to correct it.

Like a human text editor, sometimes a mutation passes the correcting enzyme and remains. As the mutant virus particle replicates, its entire genome, including the site of the mutation, is duplicated and carried over by future generations of the virus.

So how do you know if the virus has mutated? That’s where a virologist comes in. Virologists have worked tirelessly to sequence all the variants that are infecting people. The original virus, found in Wuhan, is being used to compare it to mutant variants of the coronavirus.

What is a variant?

Simply put, “a variant is a version of the virus that has accumulated enough mutations to represent a separate branch in the family tree.” He says Infectious Disease Expert Dr. Amesh Adalja, Principal Investigator at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Every mutation and strain of a virus is a variant, but every variant is not a strain.

Most of the variants are not cause for concern. This is because the mutations have not produced any drastic changes in the virus in question. However, when multiple mutations have occurred, they can sometimes affect the way the virus behaves, spreads, or infects people. That’s when a variant becomes a ‘worrying variant’. A classic example is the new variants that are spreading across parts of the UK, Africa and Brazil.

Scientists are closely monitoring SARS-CoV-2 variants to understand how genetic changes in the virus could affect its infectivity (and therefore its spread), severity of disease, treatment, and effectiveness of the viruses. vaccines available. He says Dr. Thomas Russo, professor and chief of infectious diseases at the University at Buffalo in New York.

What are the new variants in circulation?

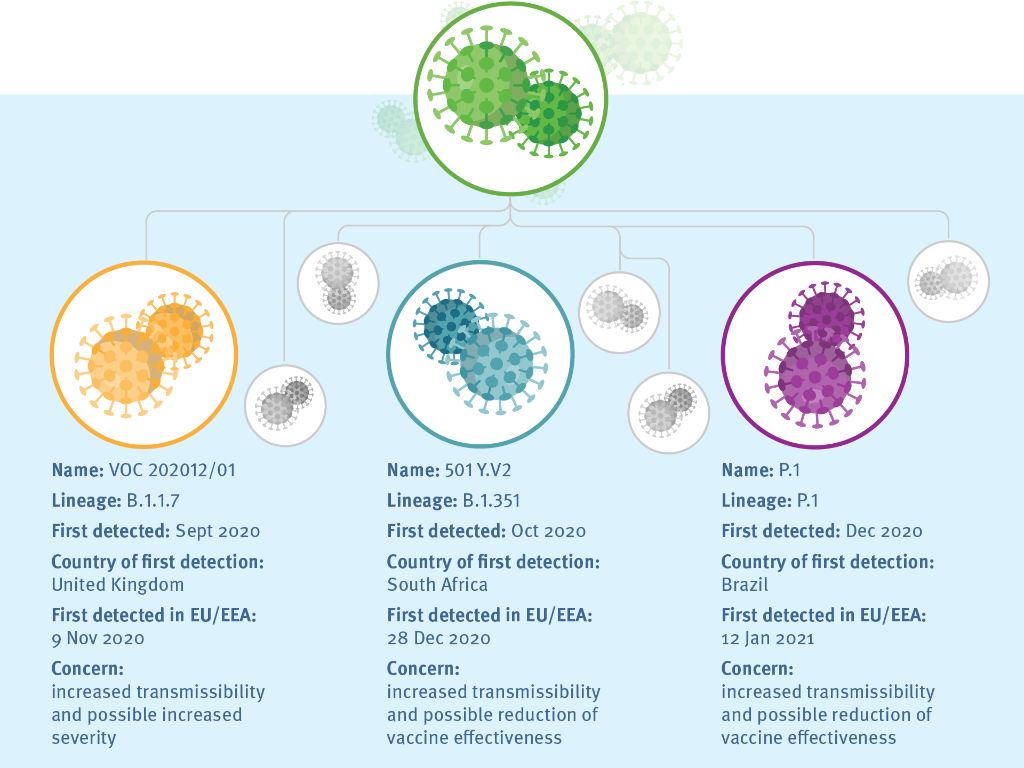

A variant of SARS-CoV-2 known as B.1.1.7 has spread across the UK since December 2020 and cases are now appearing around the world. Scientists have found some evidence that this variant has a higher risk of death compared to other variants.

An infographic that talks about the latest SARS-CoV-2 variants that are spreading. Image credit: European Center for Disease Prevention and Control

In South Africa, another variant of SARS-CoV-2 has emerged known as B.1.351. It has some similarities to the UK variant and can also re-infect people who have recovered from other COVID-10 variants. There is also some evidence that the AstraZeneca and Moderna vaccine are not as effective against this variant.

A variant known as P.1 has emerged in Brazil and was first discovered in people Travel from the South American country to Japan. There is some evidence to suggest that this variant may affect the way antibodies react with the virus. The P.1 variant mutation prevents antibodies from recognizing and neutralizing the virus.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and PreventionAll of these three variants share a specific mutation called D614G that allows it to spread more quickly.

With new variants constantly emerging, it is important that we are at the top of our genome sequencing game. By doing this, we can find new variants that are of interest to public health (since they can be more infectious, cause more serious diseases, develop a vaccine or immune resistance) and we can get ahead. However, ignoring these new emerging mutations will not make them go away and can be detrimental to us in the long run.

[ad_2]