[ad_1]

The novel and elegant SAMSON trial largely answers the nagging question of statin side effects.

This has important implications because statins can be the most studied class of any drug. More than 130,000 patients have been enrolled in placebo-controlled trials; the results show a consistent 25% relative reduction in future cardiac events.

However, many patients discontinue the drug due to adverse effects, most often myalgia. Large observational studies report a 20% to 50% higher rate of myalgia in statin users than in non-users.

But in blinded randomized controlled trials (RCTs), people taking statins have about the same lower rates of adverse effects as those taking placebo.

One way to explain the discrepancy between observational studies and RCTs is that statin trials have run-in periods that exclude patients who report adverse effects. Another explanation is the nocebo effect, when a negative expectation produces a negative result.

An Italian group has published one of the best examples of nocebo effects. Three groups of men were given the beta-blocker atenolol: one group was given no information, another group was told about the drug but no side effects, and a third group was told about possible erectile dysfunction. The rates of erectile dysfunction in each group were 3%, 15%, and 31%, respectively.

The SAMSON trial

In the SAMSON trial, presented at the American Heart Association (AHA) 2020 Scientific Sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine, James Howard and his colleagues at Imperial College London tested the nocebo effect of statins.

They used a so-called n-of-1 trial design in which each patient acts as their own control. This design is ingenious because it reflects what doctors do in practice. Start taking a medicine and see if it makes the person feel better; If you’re not sure, stop it, watch for a while, and then restart.

The key difference in SAMSON is that patients and doctors were blinded to the treatment. The trial randomized 60 patients who had previously discontinued statins due to side effects to 12 one-month periods consisting of no drug, placebo, and statins. All but 11 patients completed the 12-month trial.

The patients recorded the intensity of symptoms (0-100) every day on a smartphone app.

The main outcome of the study was the relationship between the excess intensity of symptoms caused by placebo and the excess intensity of symptoms caused by the statin.

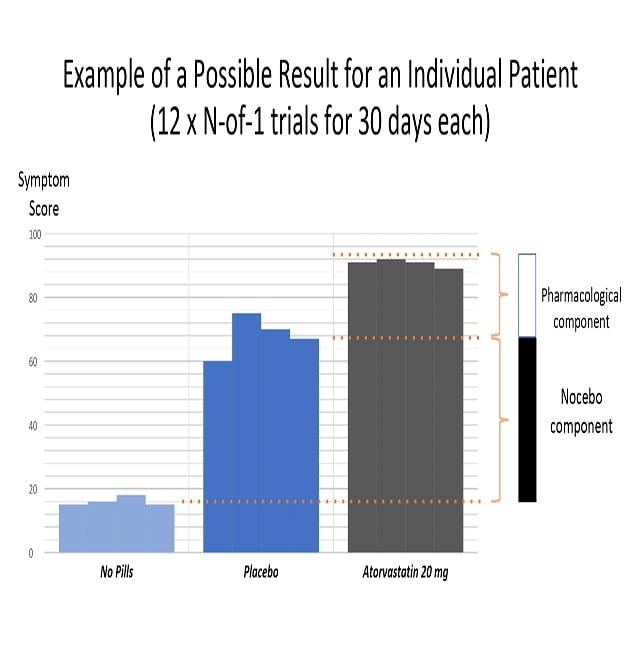

The following graph shows how the proportion of nocebo was calculated. First, the researchers recorded the difference in symptom scores between not taking pills and taking a placebo. This is the ratio of nocebo (that is, the ill effects of negative expectations from the pill). The authors then recorded the statin symptom score, which includes both the nocebo effect and the drug’s pharmacological effects.

Three main results

The mean symptom score for all patients was 8.0 during the pill-free months, 15.4 during the placebo months, and 16.3 during the statin months. The difference in symptom scores between the placebo and statin months and the pill-free months was highly significant (P <0.0001). However, the difference in symptom scores between the placebo and statin months was not significant (P = .39). To calculate the nocebo effect, they divided the symptom score of the nocebo component by the proportion of statins, for a nocebo proportion of 0.9:

|

intensity of symptoms with placebo (15.4) – intensity of symptoms without pills (8.0) _____________________________________________________________ intensity of symptoms with statins (16.3) – intensity of symptoms without pills (8.0) |

The authors concluded that patients actually have symptoms when taking statin tablets. But, more importantly, 90% of these symptoms are also triggered by placebo pills.

Statin side effects, therefore, are primarily caused by the act of taking pills. Six months after completing the trial, 30 of the 60 patients who were shown their personal results had successfully restarted statins.

My comments

The results of any trial should be considered in the context of previous data.

Before SAMSON, the evidence for the nocebo effects of statins was strong. The most convincing RCT of statins in this regard was the lipid-lowering group of the ASCOT trial, which compared atorvastatin versus placebo in 10,000 patients. ASCOT-LLA had both a blind phase and an open continuation. In the blind phase, there were no significant differences in muscle-related symptoms, but in the open phase, significantly more patients in the statin group reported muscle symptoms.

Clinicians can use the SAMSON results in the same way as Imperial College researchers: to convince some previously statin-intolerant patients to restart a drug that reduces cardiac events. That’s a big problem.

Another general message from SAMSON is for clinical researchers. If expectations can have such a large effect, imagine the difference in expectations between those in the procedure arm of, say, an atrial fibrillation ablation versus a drug trial. Or in a trial of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) versus medical therapy? Expectations are especially relevant with the measurement of outcomes prone to subjective bias, such as quality of life.

My favorite message from SAMSON is how it informs the art of medicine. Experienced physicians are well aware that getting the best result from a drug or procedure transcends pharmacology or physiology. It means managing the complex neurophysiology of placebo and nocebo effects. Such effects can come from simple expectations of reward or harm, social learning (think Internet), and even Pavlovian conditioning.

Doctors must be aware of our words and actions. Yes, patients must be informed, but it also makes sense to use all the tools of human nature to obtain a positive result. The practices of showing a patient and their family a beautiful angiographic result after PCI or being optimistic after AF ablation should not be discounted. And when we prescribe a treatment, there are many reasons to be positive.

The word “doctor” originated from the Latin verb “docere”: to teach. I will save the SAMSON test to my phone or computer and use it to teach patients about the power of expectations and the nocebo effect of statins. When, for example, a patient reports side effects of statins, rather than reducing the dose of the statin, reinforcing that the drug is causing the symptom, a better tactic would be to withdraw the SAMSON trial and teach about the nocebo effect.

However, empathy is still vital. Patients who report side effects of statins have real symptoms; they should not be discarded. SAMSON simply says that the side effect is not of the statin but from the statin pill.

The SAMSON researchers have wonderfully shown that being a healer means more than writing a prescription or moving a catheter. So I say thank you.

John Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Kentucky, and is a writer and broadcaster for Medscape. Take a conservative approach to medical practice. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of the medical evidence.

Follow John Mandrola on Twitter

Follow theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology at Twitter

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube

[ad_2]