[ad_1]

Long ago, in southern Europe, modern humans and Neanderthals had at least one encounter that resulted in children. While the flirtations between our two species are now well documented, no one could have foreseen how bleak they would affect our world 60,000 years later.

A resulting stretch of Neanderthal DNA spread throughout our populations as it was passed down from generation to generation, even as the Neanderthals themselves became extinct. About 50 percent of people in South Asia and 16 percent of people in Europe now carry this length of DNA, which scientists have now linked to the most serious form of COVID-19.

According to the new research, those with this genetic inheritance are three times more likely to require mechanical ventilation once they contract the virus, explains evolutionary anthropologist Hugo Zeberg of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

Scientists have struggled to understand what makes some people more vulnerable to SARS-COV-2 than others. The disease has now claimed more than a million human lives.

While pre-existing underlying conditions and contributing social inequalities account for a large part of our vulnerability, a significant portion of people who are young and healthy still stubbornly persist, but inexplicably end up with severe respiratory problems, while their equally healthy peers only they experience the mildest. symptoms.

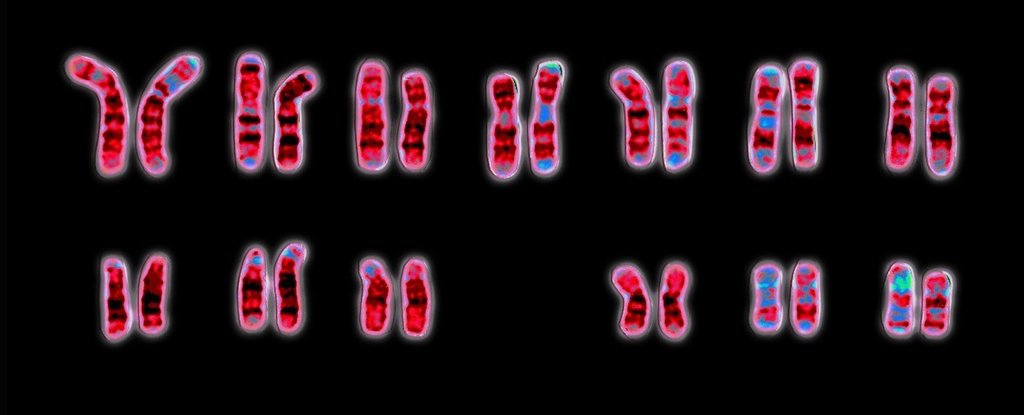

Zeberg and geneticist Svante Pääbo from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan analyzed genetic data from 3,199 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and found that certain genetic variants on chromosome 3 are found together in the population more frequently than if they were mutations. random.

Such a long length of DNA, spanning six genes and totaling 49.4 thousand bases passed together, suggests that this variation was introduced into the human genome together, meaning it was inherited.

Previous research linked this genetic region to patients who had a severe reaction to SARS-CoV-2 and required hospitalization.

So Zeberg and Pääbo investigated our extinct human relatives to see where this length of genes came from. They didn’t find any of these specific genetic variants in the Denisovan genome, and some of them were found in two Siberian Neanderthals. But a Neanderthal from Croatia shared most of the similarities.

These results are “consistent with this Neanderthal being closer to the majority of Neanderthals who contributed DNA to modern people,” the researchers wrote.

Zeberg and Pääbo calculated that it was highly unlikely that this combination of genes came from a shared ancestor of humans and Neanderthals, meaning that they were introduced when our two species interbred.

We don’t yet know why this fragment of chromosome 3 increases the risk of serious disease.

“This is something that we and others are now investigating as quickly as possible,” explained Pääbo.

Distribution and prevalence (pie charts) of Neanderthal genetic variants. (Zeberg et al., Nature, 2020)

Distribution and prevalence (pie charts) of Neanderthal genetic variants. (Zeberg et al., Nature, 2020)

The team suspects that in the past these genes may have been shown to be an advantage for some people, perhaps against another pathogen. An earlier study hinted that Neanderthal DNA might have provided protection against ancient viruses.

This may explain why this now-unfortunate variant of chromosome 3 is prevalent in some populations, such as Bangladesh, where 63 percent of people have it, but it is almost absent in others, such as Africa.

This distribution could explain why people of Bangladeshi descent in the UK are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 compared to the rest of the population.

“It is surprising that the genetic inheritance of Neanderthals has such tragic consequences during the current pandemic,” said Pääbo.

Last week, another team identified a possible immune mechanism that may also contribute to severe cases of coronavirus.

However, these genetic pieces of the coronavirus puzzle do end up fitting together, it’s important to remember that environmental factors also play a role in whether we contract the disease in the first place, and that’s something we have control over today.

This research was published in Nature.