[ad_1]

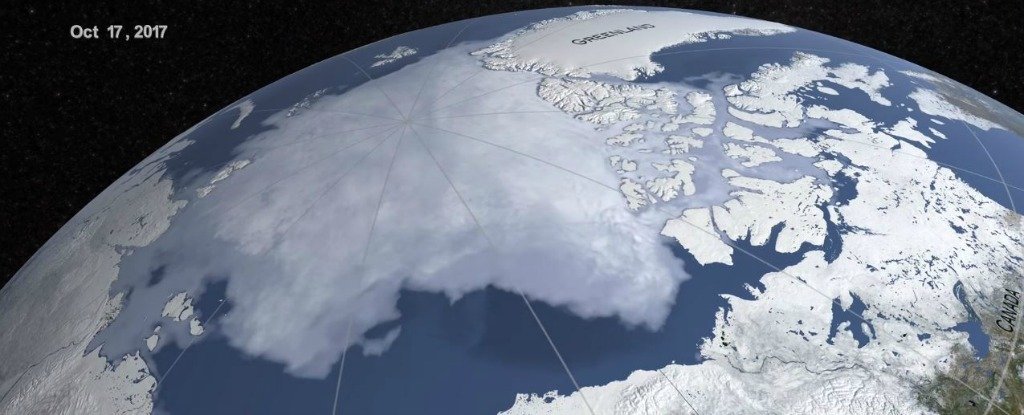

US government scientists reported Monday that the Arctic Ocean’s floating ice sheet has shrunk to its second lowest extent since satellite records began in 1979.

As of this month, only once in the past 42 years has Earth’s frozen cap covered less than 4 million square kilometers (1.5 million square miles).

The trend line is clear: the extent of sea ice has decreased by 14 percent per decade during that period.

The Arctic could see its first ice-free summer starting in 2035, researchers reported in Nature Climate Change last month.

But all that melting ice and snow doesn’t directly raise sea level any more than melted ice cubes cause a glass of water to overflow, raising an uncomfortable question: who cares?

Of course, this would be bad news for polar bears, which are already on a glide path to extinction, according to a recent study.

And yes, it would certainly mean a profound change in the marine ecosystems of the region, from phytoplankton to whales.

But if our fundamental concern is the impact on humanity, one might legitimately ask, “So what?”

It turns out there are several reasons to be concerned about the consequences of declining Arctic sea ice.

Feedback circuits

Perhaps the most basic point to make, the scientists say, is that a shrinking ice sheet is not only a symptom of global warming, but also a driving factor.

“The removal of sea ice exposes the dark ocean, which creates a powerful feedback mechanism,” Marco Tedesco, a geophysicist at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, told AFP.

Freshly fallen snow reflects 80 percent of the Sun’s radiative force back into space.

But when that mirror-like surface is replaced by deep blue water, roughly the same percentage of Earth’s warming energy is absorbed instead.

And we’re not talking about a postage stamp area here: the difference between the average ice sheet minimum from 1979 to 1990 and the lowest point reported today, over 3 million km2, is twice the size of France, Germany and Spain together. .

The oceans have already absorbed 90 percent of the excess heat generated by man-made greenhouse gases, but at a terrible cost, including altered chemistry, massive marine heat waves, and dying coral reefs.

And at some point, scientists warn, that the liquid heat sponge can simply become saturated.

Altering ocean currents

Earth’s complex climate system includes intertwined ocean currents driven by wind, tides, and something called thermohaline circulation, which in turn is driven by changes in temperature (“thermo”) and salt concentration (“haline”).

Even small changes in this Great Oceanic Conveyor Belt, which moves between the poles and through the three major oceans, can have devastating climate impacts.

Nearly 13,000 years ago, for example, when Earth was transitioning from an ice age to the interglacial period that allowed our species to flourish, global temperatures plummeted several degrees Celsius.

They jumped again about 1,000 years later.

Geological evidence suggests that a slowdown in thermohaline circulation caused by a massive and rapid influx of cold, fresh water from the Arctic region was partly to blame.

“Fresh water from melting sea ice and land ice in Greenland disturbs and weakens the Gulf Stream,” part of the conveyor belt that flows into the Atlantic, said Xavier Fettweis, a research associate at the University of Liege in Belgium.

“This is what allows Western Europe to have a temperate climate compared to the same latitude as North America.”

The huge ice sheet on Greenland’s land mass saw a net loss of more than half a trillion tonnes last year, all flowing out to sea.

Unlike sea ice, which does not rise sea level when it melts, runoff from Greenland does.

That record amount was due in part to warmer air temperatures, which have risen twice as fast in the Arctic as around the world.

But it was also caused by a change in weather patterns, particularly an increase in sunny summer days.

“Some studies suggest that this increase in anticyclonic conditions in the Arctic in summer is due in part to the minimal extent of sea ice,” Fettweis told AFP.

Bears on thin ice

The current trajectory of climate change and the advent of ice-free summers, defined by the UN IPCC’s climate science panel as less than 1 million km2, would in fact starve polar bears to extinction by the end of the century. , according to a July study in Nature.

“Human-caused global warming means that polar bears have less and less sea ice to hunt in the summer months,” Steven Amstrup, lead author of the study and lead scientist at Polar Bears International, told AFP.

“The final trajectory of polar bears with incessant greenhouse gas emissions is disappearance.”

© Agence France-Presse