[ad_1]

In A perfect spyHis most autobiographical novel, John le Carré describes its protagonist, the morally committed double agent Magnus Pym, with a lithe gait, “his body leaning forward in the best tradition of the Anglo-Saxon administrative class. In the same attitude, whether static or in motion, the English raised flags over distant colonies, discovered the sources of great rivers, stood on the decks of sinking ships ”.

The British imperial decline and the dubious strategies of the political classes and intelligence services to disguise that decline during the cold war, form the backdrop for many of the 25 novels by le Carré, who died at 89 years of age. Espionage was the genre that earned him fame. But he used it as a platform to explore broader ethical issues and the human condition with such insight that many fellow authors and critics regarded him as one of the greatest English-language novelists of the 20th century.

Like the character of Joseph Conrad, Charles Marlow, and Philip Roth’s Nathan Zuckerman, George Smiley de le Carré recurs in his novels, reminding readers of the author’s enduring concerns. Smiley, a heavy but not unsympathetic middle-aged spy hunter with a turbulent private life, is the antithesis of Ian Fleming’s James Bond, who seduces women and dismantles the nefarious plots of enemies with the kind of naturalness that led Le Carré to make fun of him. like a “gangster”.

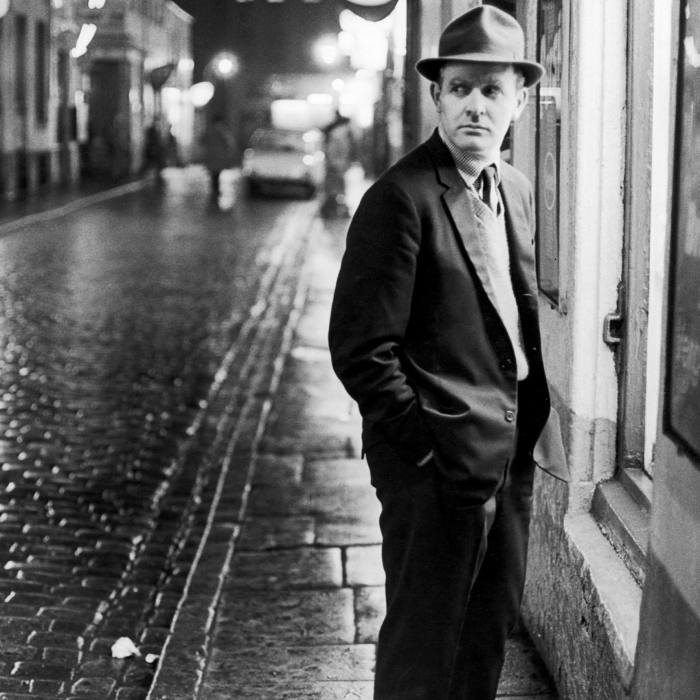

John le Carré in London in February 1964. He worked for MI5 and MI6 in the 1950s and early 1960s © The LIFE Picture Collection via

Gary Oldman as George Smiley in ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy’. The character is repeated in le Carré’s novels

Le Carré had a keen sense of humor and spoke in sentences as elegantly constructed as his prose. “A good writer is an expert on nothing except himself,” he once said. “And on that subject, if he’s wise, he bites his tongue.”

However, he made good use of his first-hand knowledge of espionage, deception, and the weaknesses of human character.

Born in 1931 in Poole, on the south coast of England, le Carré’s real name was David John Moore Cornwell. His mother left the family home when he was five and his father was a “con artist, fanciful, occasional prisoner,” as he wrote in his memoirs: The tunnel of the dove.

In 1948 he left his private English school, Sherborne, and traveled to Switzerland to study languages at the University of Bern. There she was inspired to “embrace the German muse as a surrogate mother”, immersing herself in the works of Johann von Goethe, Heinrich von Kleist and Georg Büchner.

Le Carré joined the British Army Intelligence Corps in 1950, questioning people in Austria who had crossed from communist eastern Europe to the west. After a stint at Oxford University, he taught for two years at Eton, the British private school whose students he later described as “an absolute curse on earth, leaving that school with a sense of entitlement and an over-educated cultural stance.”

In the late 1950s and early 1960s he worked for MI5, the British national intelligence service, and then for MI6, his foreign counterpart, which sent him to Bonn and Hamburg. By his own account, his duties were minor. But he gained enough experience to write three spy novels, the third of which, The spy who came from the cold, was an international bestseller and became a hit movie starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom.

Richard Burton and Robert Hardy in ‘The Spy Who Came From The Cold’. The book on which the film was based was an international bestseller | © Paramount / Kobal / Shutterstock

In one of his last public appearances, at the German embassy in London in March, Le Carré explained that the world of spies in his novels, a scene of betrayal, broken lives and corroded morality, came mainly from his own imagination. It broke new ground for the genre by stripping its characters of glamor and constructing plots that resolutely avoided simple confrontations between good and evil.

He was not a neutral observer of the cold war and claimed that whatever the shortcomings of Western political systems, they should not be compared to one-party dictatorships. After the end of communism, however, he said: “The spies did not win the cold war. They made absolutely no difference in the long run. “

In his post-Cold War novels, le Carré emerged as a staunch critic of American and British foreign policy. Africa, Central America, the former Soviet Union, and other regions were the setting for novels that dissected the arms trade, drug trafficking, and the global pharmaceutical industry.

Le Carré married Ann Sharp in 1954 and the couple had three children, Simon, Stephen, and Timothy. After his divorce in 1971, he married Valérie Jane Eustace, who contributed her editorial experience to his work. They had a son, Nicholas, a novelist who writes under the name Nick Harkaway.