[ad_1]

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project is so important to the Horn of Africa country that it decided to finance its construction on its own, after international lenders refused. The hydroelectric power that the Blue Nile dam will produce is essential in a country where more than half the population does not have access to electricity. But it’s not just about electrical power.

When the talks about the dam rupture last month between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia, it was not about sharing water resources. It was a case of regional rivalries that triumphed over understandings of science and cooperation.

The project is “a declaration that Ethiopia is an important and powerful country that can go it alone and assert itself on the regional stage,” says Awol Allo, an Ethiopian analyst.

Egypt, 1,000 miles downstream and dependent on the Nile for fresh water and irrigation, sees the dam as a threat to national security. Sudan, which will benefit, is sandwiched between Egypt and Ethiopia and is also unwilling to get angry.

“For 50 or 60 years, Egypt was the largest geopolitical player” in the region, says analyst Rashid Abdi. Today, the new governments “are becoming more assertive … and acting independently,” he says. “It’s a natural progression that Egypt finds uncomfortable.”

Amman, Jordan

When African Union-mediated talks between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan over a Nile River dam broke down again last month, it did not mark a new disagreement over sharing vital water resources.

Rather, it was a case of regional rivalries that surpassed the understandings on science and cooperation that have been established by African and Western mediators in multiple draft agreements.

Since then, Egypt’s media have beaten the drums of war, and a dispute over the border territory between Sudan and Ethiopia has erupted into violence.

At the center of the dispute is the Great Renaissance Dam of Ethiopia (GERD), built by successive governments in Addis Ababa with the goal of lifting millions of people out of poverty.

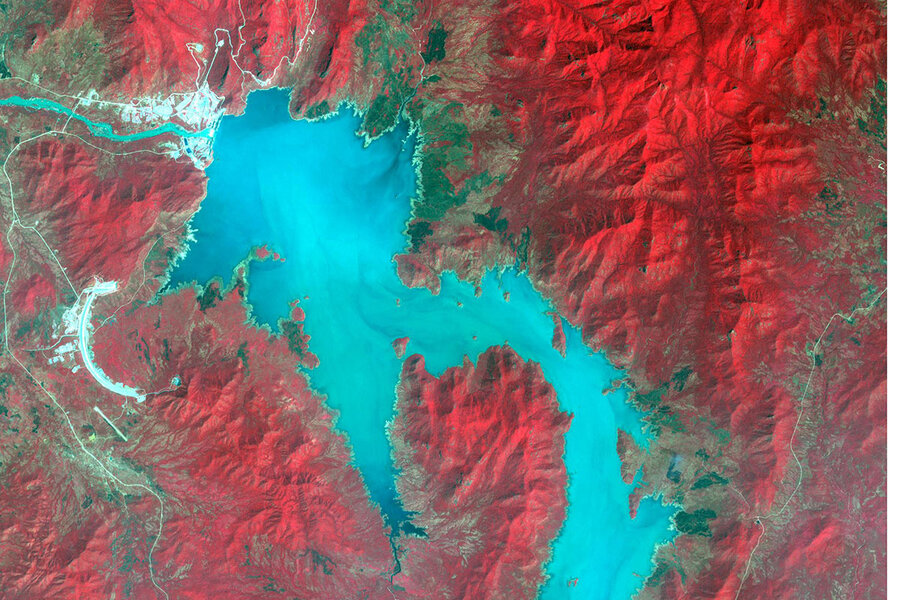

The turbines at the dam, located near the source of the Blue Nile in northwestern Ethiopia, will generate 6,000 megawatts of hydroelectric power, which is critical in a country where more than half the population, some 50 million people, do not they have access to electricity. energy demand increases by 30% annually.

The solution to water security concerns resulting from Egypt and Sudan, observers say, is simple: coordination and data sharing.

Yet even amid indications that the resurgence of traditional American diplomacy could help resolve the dam dispute, observers say mediators must also confront stronger currents than the Nile itself: nationalism, territorial disputes and a fight for supremacy in the Horn of Africa.

Regional supremacy

For Ethiopia, the dam project promises to boost the country’s rise as a geopolitical actor. Even amid the fight for the future of the country that erupted into war last November in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia, the dam remains a cause that unites the diverse nation.

“There has been a feeling of injustice among the government and the Ethiopian people in general, that as a poor country we have not been able to use a natural resource that springs from Ethiopia,” says Awol Allo, an Ethiopian analyst and lecturer in the UK. Keele University.

“This dam project marks the rebirth of the Ethiopian state after decades of shame, poverty and famine with which it has been identified.”

A sense of personal investment and national unity around the dam solidified after the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and other lenders refused to fund the GERD. Ethiopia in 2010 decided to do it alone, paying for it with government funds and bonds purchased by private citizens, and began construction of the project in 2011.

“All Ethiopians see themselves as interested in a project that is not just about energy needs, but about a declaration that Ethiopia is an important and powerful country that can do it alone and assert itself on the regional stage,” says Allo.

Downstream drama

Despite the draft agreements, water sharing disputes between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia have only deepened since GERD construction was completed in 2020 and Addis Ababa began filling the reservoirs in July.

Downstream countries, long accustomed to the unrestricted flow of the Nile for their agriculture and fresh water, are alarmed by the potential impact of the dam on their water and food security.

Egypt, 1,000 miles downstream from the dam, has historically claimed most of the water from the Nile and views GERD as a threat to national security. Egypt currently depends on the Nile for 90% of its fresh water and the vast majority of irrigation water for crops to feed its 105 million citizens. It is also concerned about possible floods and droughts.

Egypt and Sudan regret the lack of technical studies and environmental and social impact assessments of the downstream dam.

Tensions are now high as Addis Ababa is set to fill the dam’s reservoir with an additional 11 billion cubic meters this year after the initial 4.9 BCM it filled in July 2020. The dam has a total capacity of 74 BCM . “The biggest problem is not knowing how Ethiopia intends to use and operate the dam, at what time of year, in what quantities and what will be the impact,” says Amal Kandeel, an environmental and policy consultant and former director of Climate Change. Middle East Institute Environment and Safety Program. “Downstream countries cannot plan without knowing; they need clarity.

“Egypt will not benefit from the dam,” he says. “But if there is coordination, facts, evidence and data shared transparently at a minimum, it will reduce any potential harm.”

For Egypt, a “humiliation”

Egypt’s inability to stop or influence the project has become symbolic of the government’s introspective approach over the past decade and its withdrawal from the Arab and African scene, which national critics say has dramatically reduced Egypt’s geopolitical importance.

Egyptian insiders say privately that the prospect of Ethiopian control over water and food security in the most populous Arab country is seen as “a humiliation”, pushing Cairo’s hard line.

“For 50 to 60 years, Egypt was the biggest geopolitical player, not just in the Middle East, but also in the northeast of the Horn of Africa,” says Horn of Africa analyst Rashid Abdi.

“Times have changed, there are new governments that are becoming more assertive on the regional and world stage and act independently,” he says. “It’s a natural progression that Egypt finds uncomfortable.”

Egypt has lobbied for intervention by the United States, its Arab allies and the UN Security Council. In June, Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry warned of a conflict if the United Nations did not intervene.

After the collapse of the talks last month, the Egyptian state-influenced media outlets clamored for the use of “force” against Ethiopia, advocating surgical strikes on GERD’s electrical infrastructure.

For Sudan, it’s good, but …

Meanwhile, regional alliances and a centuries-old border dispute have transformed Ethiopia’s northwestern neighbor from a quiet supporter of the dam to a saboteur.

Observers and experts agree: the benefits of GERD for Sudan are many.

The dam, 32 kilometers from the Sudan-Ethiopia border, will reduce the flooding that has devastated Sudan in the past. The Blue Nile floods destroyed a third of the country’s cultivated farmland last year, destroyed 100,000 homes and killed 100 people, exacerbating Sudan’s economic crisis.

Reducing flooding and sharing irrigation water would help Sudan cultivate more than 50 million hectares of arable land abandoned due to flooding and mismanagement, a critical boost for an agricultural sector that is the largest employer in Sudan and accounts for 30% of the country’s gross national income. product.

Ethiopia has also committed to exporting cheap electricity to Sudan.

“Honest people in Khartoum will tell you that the dam is a positive outcome from all logical, logistical and economic perspectives. Objectively, Sudan would benefit from the dam, ”says Jonas Horner, Sudan analyst and deputy director for the Horn of Africa at International Crisis Group.

“But it’s not as simple as that,” he says, pointing to Sudan’s need to balance regional alliances.

Khartoum, militarily close to Egypt, diplomatically indebted to Ethiopia and financially and politically dependent on Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which are allied with Egypt, is reluctant to appear to support the dam, on the one hand, or collapse. hard in Addis Ababa, on the other.

This tricky balancing act was interrupted in December by the violent reign of a border dispute between Sudan and Ethiopia that stretches back a century.

Sudanese patrols have reportedly been shelled by Ethiopian militias, and the Sudanese army and Ethiopian federal forces have clashed several times this month.

Ethiopian officials blame Cairo for stoking tensions, citing an Egyptian plot to prolong the conflict and derail the completion of the GERD.

Traditional American Diplomacy

Observers agree that the dispute provides an opportunity for the Biden administration to demonstrate its promised return to traditional American diplomacy.

The Trump administration’s few forays into the GERD dispute favored Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, a Trump ally. Last July, the Trump administration partially suspended US assistance to Ethiopia after Addis Ababa rejected a draft agreement compiled by Washington that it deemed strongly favored Cairo. President Donald Trump publicly warned that Cairo would “blow up that dam” if the talks failed.

In contrast, President Joe Biden’s Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, promised at his confirmation hearing last month to carry out an “active engagement” to address rising tensions that “has the potential to be destabilizing across the world. Horn of Africa, “indicating that he is considering appointing a United States special envoy to the Horn of Africa.

But observers warn that the Biden administration must unravel the web of regional politics, nationalist fervor and power plays to get all three states back to basics: water.

“The war in Tigray has created instability in the state of Ethiopia, and now we have the problem of the border with Sudan which is clearly related to the problem of GERD. There are national actors in each of these countries that pressure external actors to promote their interests, ”says Mr. Allo.

“It will be difficult for any American administration with all the goodwill in the world to fix things.”