[ad_1]

Young volunteers take to the streets to mobilize against COVID-19 in Ethiopia. Photo by UNICEF Ethiopia. CC-BY 2.0

Several Ethiopian activists were arrested in 2020 for violating the country’s COVID-19 restrictions, raising questions about whether the government has used those protocols to silence criticism.

Ethiopia was below a state of emergency (SoE) to counteract the spread of COVID-19 from April to September 2020.

On April 20, Elizabeth Kebede, a lawyer, activist and outspoken critic of the government, was stopped in Addis Ababa for allegedly “spreading false rumors” about the COVID-19 situation in Harar, the main city in the Harari region.

In March, shortly after Ethiopia recorded its first COVID-19 case, Elizabeth had posted on Facebook that he knew people who, despite coming into contact with others who had tested positive for COVID-19, had not entered quarantine.

Elizabeth was extradited to Harari on the same day of arrest, according to Ethiopian Women Lawyers Association (EWLA) where she works as a volunteer. She was released on May 6 without charge.

EWLA argued that the Harari police did not have jurisdiction to bring cases against Elizabeth as her permanent address is in Addis Ababa. They also say there was no legal need to transfer her to Harari.

Ethiopian journalist Yayesew Shimelis He was also arrested without charge, on March 27, 2020. That was a day after he posted a video on the YouTube channel Ethio Forum, which he runs, reporting that the central government was preparing 200,000 graves to accommodate the deaths of COVID- 19, citing anonymous sources. Yayesew was released on April 23.

the Ministry of Health and the Prime Minister’s Office they have rejected the claims made in the video. The first said that the video “should be condemned” and the second that “law enforcement officers […] they have been mandated to take action against individuals and groups that unleash terror on people’s health and sense of security. “

Yayesew hosts a weekly political program on Tigray TV, a channel owned by the Tigray regional government, a major force opposing the Addis Ababa government. The journalist is known in Ethiopia for being critical from the prime minister Abiy ahmed.

After witnessing the fierce reaction on social media to her video report, Yayesew tweeted saying that “I did not imagine that the news could be so shocking.”

Yayesew told Global Voices that YouTube removed his video report and Facebook removed a post in which he had shared the video. He says that Twitter also suspended his account.

Vague provisions

Directive issued The Council of Ministers to implement the state of emergency had provisions that, according to experts, undermined freedom of expression and unleashed a chilling effect on the press.

For example, Article 3/26 it prohibited the publication of information that “could destabilize society.”

Disseminating any information that makes society unstable and puts psychological pressure on society in relation to COVID-19 and related issues is prohibited.

As well, Article 4/10 declares that the information disseminated by the media should not cause commotion.

Government communication professionals and private media institutions should disseminate information, news analysis or related information on COVID-19 and related topics without exaggerating or undermining relevant information and without causing undue shock and terror.

The cost of censorship

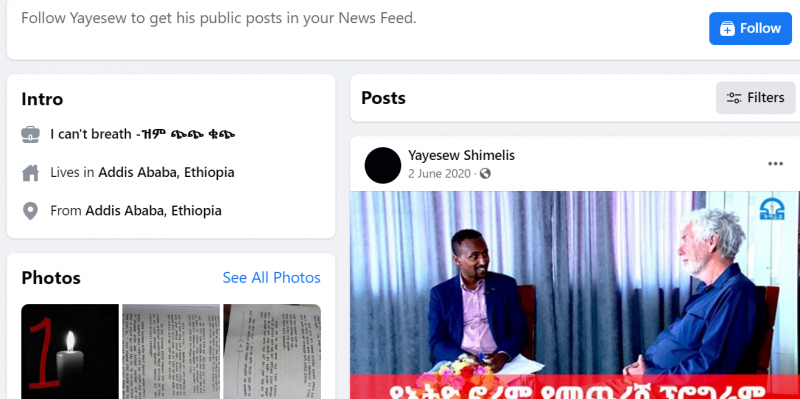

A screenshot of Yayesew’s Facebook page taken on February 25, 2021

Since his release, Yayesew is no longer so outspoken. Your Facebook bio it has since been updated and says, “I can’t breathe, I just keep quiet.”

In a video he uploaded to YouTube on June 2, 2020, Yayesew says she had to stop her show on Tigray TV’s EthioForum “sadly” for a reason she “cannot reveal at the moment”

Since then, Elizabeth Kebede has left Ethiopia for an undisclosed country. In to facebook post As of November 2020, he explained his reasons for applying for asylum abroad and indicated that his case was not closed, it was only transferred from Hariri to Addis Ababa.

His Facebook post, which has since been deleted, included an accompanying statement from Ethiopia’s permanent mission in Geneva that read read:

Ms. Elizabeth’s posts have seriously undermined the safety, equality and dignity of certain ethnic groups and would likely incite violence and disrupt public safety.

This article is part of a series of posts examining interference with digital rights under lockdown and beyond during the COVID-19 pandemic in nine African countries: Uganda, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Algeria, Nigeria, Namibia, Tunisia, Tanzania, and Ethiopia. The project is funded by the African Digital Rights Fund of The Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA).

[ad_2]