[ad_1]

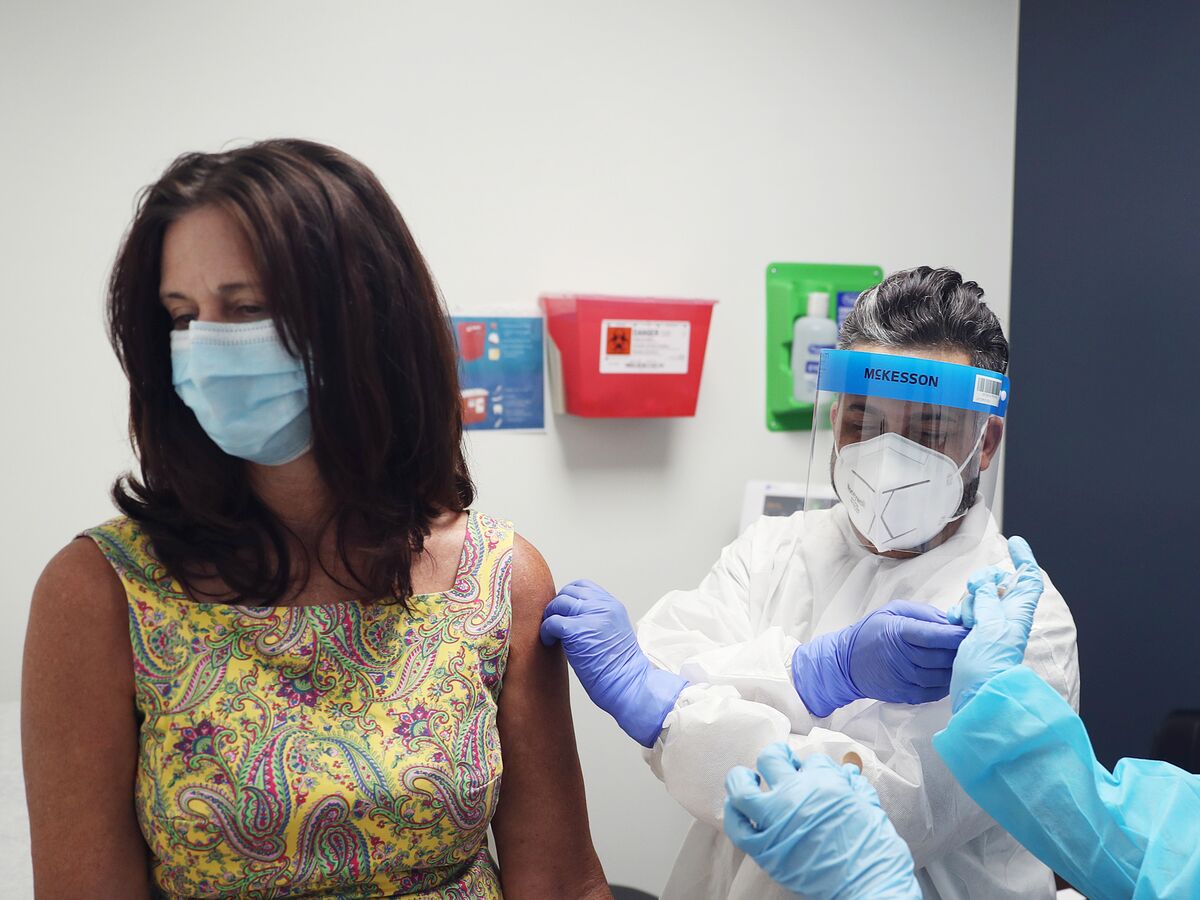

Photographer: Joe Raedle / Getty Images

Photographer: Joe Raedle / Getty Images

Eddie Rice believes in vaccines. The Melbourne locksmith has taken a beating in the past and understands that they go through rigorous testing before they are implemented. This time around, as investigators move forward with potential shots to protect the world against Covid-19, he’s not so sure.

“This is a pretty unique one, just because it’s going to be very fast,” said Rice, 29. “I don’t know enough about science to know 100% that it’s safe.”

Governments and drug manufacturers have long faced skepticism, and even hostility, from a small but noisy group of anti-vaccination activists. In the battle against the coronavirus, they may also meet the reluctance of a broader swath of the population, people like Rice, who would normally be on board.

Loss of confidence in governments, political interference and the race to create opportunity in record time are sowing doubts. Temporary study interruptions due to unexplained illnesses in volunteers, a part of vaccine development that often doesn’t make headlines, heightens anxiety. These misgivings could hamper the high-risk quest to curb a pathogen that has killed 1.1 million people.

Assuming immunizations can be successfully mass-developed, produced, and deployed, vaccine advocates will need to convince enough people that vaccines are critical to ending the crisis. In a survey of 20,000 people conducted over the summer, more than a quarter of those surveyed said they would not receive a Covid injection. Russia, Poland, Hungary and France had the lowest support, the World Economic Forum and Ipsos study showed.

A healthcare worker injects a patient with a Covid-19 vaccine during trials in Moscow.

Photographer: Andrey Rudakov / Bloomberg

The effort to overcome that feeling will begin with healthcare workers. Medical personnel are at increased risk of contracting the virus and spreading it to others, and are likely to be among the first to get vaccinated. Any concerns they may have about the quality of a vaccine could hinder its wider acceptance.

Nor should their support be taken for granted. Medical workers should be careful not to damage the trust they have earned by promoting a product in which they have no faith, he said. Sara Gorton, head of health for Unison, a UK union representing nurses, paramedics and others in the field.

“If healthcare workers are expected to advocate for the vaccine, then their natural concerns will need to be addressed in advance,” he said. “It won’t help you with the answer if you’re going to get your jab and the person giving it can’t say reassuring things.”

A study in Hong Kong earlier this year found that only 63% of nurses expressed a willingness to receive a possible Covid vaccine. He cited uncertainty about effectiveness, side effects and how long the protection would last. Support was stronger as cases increased, but decreased as infections decreased, according to researchers including Kin On Kwok, an epidemiologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

If fewer than two-thirds of nurses during an outbreak intend to get vaccinated, “we anticipate that promoting the vaccine to the general public in the post-pandemic period will be much more challenging,” they wrote.

Anxiety about China’s growing influence in the former British colony may be another factor behind the lack of conviction. A mainland-backed effort that offered free testing to all Hong Kong residents only saw a quarter of them. Chinese vaccine developers have been at the forefront of the race. Although the final stage of trials is not complete, thousands of people in China have already received doses under extensive emergency use provisions.

A major concern among doubters is that critical steps to demonstrate safety and efficacy could be carried out in a hurry, despite assurances, such as a promise in September by nine American and European developers, to avoid shortcuts in development. science.

Vaccines led by AstraZeneca Plc and Oxford University, Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE and Moderna Inc. are among those in the final stages of testing, and critical data could arrive before the end of the year, which that paves the way for emergency approvals. That feat would be accomplished by compressing into just months a development process that normally takes up to a decade. Public confidence in vaccines that have not been thoroughly tested could be low, according to analysts at HSBC Holdings Plc.

The search for a Covid shot has become increasingly politicized, reducing the number of people who are inclined to get one, according to Scott Ratzan, a physician and public health specialist at the City University of New York. Officials will need to demonstrate why an immunization that has been shown to be safe is beneficial to individuals and society, he said.

Among the majority of the public, vaccines are embraced as safe and simple ways to prevent disease, but concerns about a Covid injection have risen in recent months. Americans’ willingness to get vaccinated against the virus dropped to 50% in September from 66% in July, a Gallup poll shows.

“Most people support vaccines,” said Ratzan, who is part of a group working to increase confidence in future Covid immunizations. “We have to find the fence keepers. Are you undecided? Are they insecure? How do we target them? “

The interruptions to the trials have not helped. While it’s not unusual to pause studies to investigate potential side effects, those episodes highlight why work can’t be rushed. AstraZeneca vaccine trials in the US remain on hold after a volunteer in a trial in the UK fell ill more than a month ago. Johnson & Johnson said last week it would stop its study to investigate an ailment, which it did not specify, in a participant.

The rapid pace of studies has made people uneasy.

President Donald Trump has pushed for a vaccine ahead of the Nov. 3 election, although many companies and experts have said it is unlikely. He acknowledged earlier this month that the goal may not be met, but blamed “politics” after regulators published new standards that could delay an authorization.

Scientists dressed in full-body protective suits enter a laboratory used for coronavirus research in Pecs, Hungary.

Photographer: Akos Stiller / Bloomberg

As the virus continues to spread, the pressure to create a vaccine has increased. America’s effort to speed up delivery of a vaccine is called Operation Warp Speed.

“People are afraid, in a pandemic you would expect that, and the rush, the political proclamations have made people even more nervous,” said Seth Berkley, CEO of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the nonprofit organization that works to immunize children in poor countries and is helping lead a program to roll out future Covid vaccines around the world.

The fiascos of the past may fuel doubts in some regions. The Philippines in 2016 launched a major campaign to vaccinate children against dengue, the mosquito-borne disease, but it was discontinued after the vaccine was linked to an increased risk of serious illness in some who had not previously been exposed to the virus.

Some people will also remember an outbreak of swine flu in 1976 in the United States. Then-President Gerald Ford announced a plan to vaccinate everyone in the country, and soon more than 40 million Americans had received vaccinations. But it never became a pandemic as feared, and some of those who had been vaccinated developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis.

Suspicions that extend beyond the usual anti-vaccine movement pose an additional problem for health advocates already struggling to contain a wave of misinformation. In one example, social media posts published a false story that seven children had died in Senegal as part of a Covid vaccine trial.

AstraZeneca chief Pascal Soriot issued a statement on Friday calling the misinformation a “clear public health risk” and urging the public to stick to reliable sources after reports of a campaign in Russia to undermine the drug manufacturer’s vaccine with Oxford.

Efforts to track and counter misleading claims are increasing. UNICEF, which focuses on protecting children and is one of the largest providers of vaccines, said it forged a digital partnership with the Yale Institute for Global Health and others to create content aimed at assuming falsehoods before they get out of control. .

In the past, much of the opposition has focused on the value of “purity” and claims that vaccines contain dangerous levels of toxins, he said. Angus Thomson, a senior social scientist at Unicef.

“What we have seen is an interesting turn towards freedom,” he said. “Suddenly, vaccination is about restricting your freedom.”

Engagement with the public will also need to increase to explain how vaccines are created and how they will be implemented, said Heidi Larson, who leads the Vaccine Confidence Project, a research group. Many promising Covid injections are based on novel approaches, such as messenger RNA.

“There hasn’t been much discussion about why these vaccines can be made faster, what new technologies are used, how some can have one dose and others two,” he said. “We need to talk more about that.”

While health officials will face reluctance, and even “nefarious” behavior, from people promoting incorrect information, there is reason for optimism, according to Berkley, Gavi’s chief executive.

Advances have been made on the therapy front to help patients who become seriously ill, but a vaccine is still considered essential to the global exit strategy, especially amid concerns about long-term complications months after the initial symptoms.

“I have to believe in the bottom of my heart if we follow the processes, if we get a safe and effective vaccine that has gone through strict regulatory approval, if people start taking it and can go back to normal or near normal, that will make other people want the product, ”Berkley said.

– With the help of Rachel Chang