[ad_1]

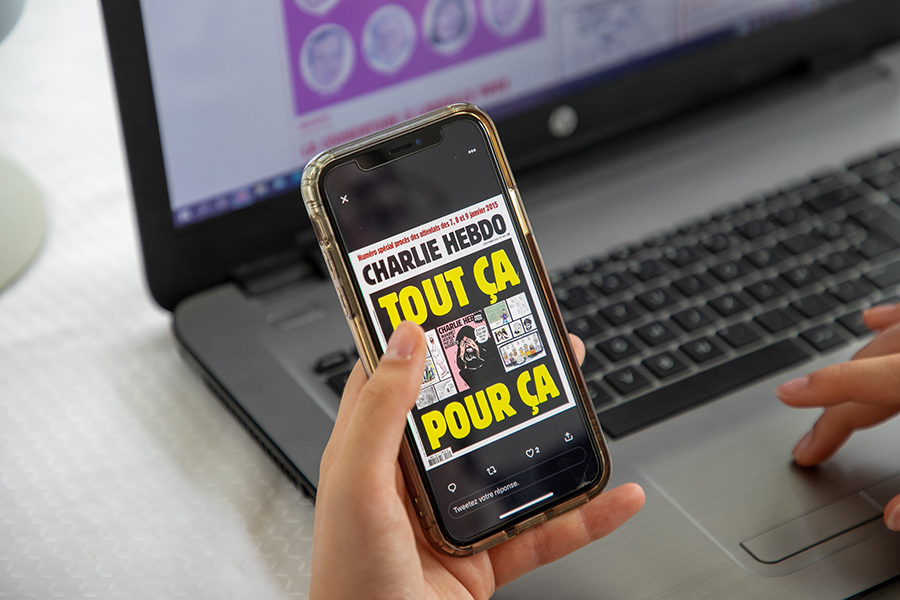

A member of the photographer’s family watches the official Twitter account of the French satirical newspaper ‘Charlie Hebdo’ as it reprints the controversial Muhammad cartoons on September 1, 2020 in Paris, France. On September 2, 2020, a Paris court will open the trial of 13 men and a woman accused of providing material and logistical support to the attackers in the run-up to the attack on the former Charlie Hebdo offices on January 7, 2015

A member of the photographer’s family watches the official Twitter account of the French satirical newspaper ‘Charlie Hebdo’ as it reprints the controversial Muhammad cartoons on September 1, 2020 in Paris, France. On September 2, 2020, a Paris court will open the trial of 13 men and a woman accused of providing material and logistical support to the attackers in the run-up to the attack on the former Charlie Hebdo offices on January 7, 2015

Image: Marc Piasecki / Getty Images

PARIS – The French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo has republished the same cartoons about the Prophet Muhammad and Islam that sparked a deadly attack on the magazine in 2015, an act that will be seen by some as a commitment to freedom of expression and by others as a reckless provocation. . The publication coincides with the start on Wednesday of the long-awaited terrorism trial of people accused as accomplices in the attack, potentially cathartic for a nation that was deeply marked by that act of brutality. The magazine published the cartoons online Tuesday and they will appear in print on Wednesday. The trial and the reappearance of cartoons that many consider offensive comes when France witnesses protests against racism and calls for a reflection on the treatment of minorities in its society, in the past and in the present. Growing sensitivity to race, ethnicity and religion has clashed with France’s traditionally strong commitment to free speech and secularism. Many traditionalists have expressed concern that the country is giving in to American-style identity politics, widely rejected in France. The editors of Charlie Hebdo wrote in the new issue that it was “unacceptable to initiate the trial” without showing the “evidence pieces” to readers and citizens. Not republishing the cartoons would have amounted to “political or journalistic cowardice,” they added. “Do we want to live in a country that claims to be a great, free and modern democracy, which, at the same time, does not affirm its deepest convictions?” President Emmanuel Macron recently found himself trying to navigate the shifting lines of cultural sensitivity. Last year, he faced widespread criticism for giving a lengthy and exclusive interview to Valeurs Actuelles, a right-wing magazine, and defended himself by saying that he had to speak to all French people. But over the weekend, he joined other political leaders in condemning the same magazine for describing a black lawmaker as an enslaved African. The attack on Charlie Hebdo was the first in a series of major Islamist attacks in Paris. On January 7, 2015, two French-born brothers of Algerian descent, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, broke into Charlie Hebdo’s offices. They killed 11 people inside with automatic shots, including the senior editor and some of their main cartoonists, and then killed a police officer on the street while making their getaway. Several people were injured. The brothers identified themselves as belonging to al-Qaida and left the magazine saying they were “avenging the Prophet,” according to survivors of the attack. Two days later, a friend of hers, Amedy Coulibaly, took hostages and killed four people in a kosher supermarket in Paris. The worst of the attacks came 10 months later, when a group of gunmen and suicide bombers from the Islamic State killed 130 people and injured more than 400 at various locations in the capital region. Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers died in clashes with the police, so after almost six years, the trial of the alleged accomplices, which is scheduled to last two months, will mark the most comprehensive broadcast of an incident that turned into a national trauma. . The defendants, including some who are not in custody and will be tried in absentia, are accused of aiding the three main attackers, including some who provided weapons and financing. Charlie Hebdo, who has a long history of skewering various subjects across the political spectrum, had also long been accused by critics of recklessly publishing material deemed racist and anti-Muslim. But after the massacre, large demonstrations in support of the magazine were held in Paris and elsewhere. “Je suis Charlie”, or “I am Charlie”, became a slogan used even by people who despised the magazine, a way of expressing their support not only for the victims but also for freedom of expression and freedom of the press . On Tuesday, Mohammed Moussaoui, chairman of the French Council of the Muslim Faith, the main organization representing French Muslims, said that the republished cartoons should not be heeded. “The freedom to caricature is guaranteed for everyone,” Moussaoui told Agence France-Presse, adding: “Nothing can justify violence.” Moussaoui said people should focus instead on the trial “which should remind us of the victims of terrorism.” “This terrorism that has struck in the name of our religion is our enemy,” he added. Most of the drawings in this week’s issue were originally published by a Danish newspaper in 2005 and included one lampooning Muhammad with a bomb in his turban. Mockery of Islam and any depiction of the prophet is considered blasphemous by many Muslims, and the drawings set off deadly riots in Muslim countries and resulted in boycotts of Danish products. As a show of solidarity with the Danish publication and in the name of freedom of expression, Charlie Hebdo republished the cartoons the following year as part of a “special edition”. Its cover depicted Prophet Muhammad saying, “It is difficult to be loved by idiots. “The cover artist, Cabu, was killed in the 2015 attack. In 2007, the Great Mosque of Paris and the association that is now the French Council of the Muslim Faith sued the editor of Charlie Hebdo for publishing three cartoons that, according to They said they had incited hatred against Muslims. The court ruled in favor of editor Philippe Val, saying the cartoons were covered by free speech. Val, who left the magazine years before the 2015 attack, told Tuesday French radio station RMC which supported the current editors’ decision to republish the cartoons. “Charlie should not only republish them,” he said, “but all newspapers should republish them.” A poll published Monday indicated that the 2015 attacks had strengthened France’s commitment to freedom of expression. According to IFOP, a survey firm, and the Jean Jaurès Foundation, a French think tank, 59% of respondents said that the magazine was “right” in publishing the cartoons in the name of freedom of expression, up from 38% in 2006. “It shows that the French are finally ruling in favor of the newspaper for daring to publish these cartoons,” said François Kraus , a political analyst who oversaw Charlie Hebdo last published a cartoon of the Prophet Muhammad on the cover of the issue after the January 2015 massacre. He was shown holding a sign that read, “I am Charlie,” with the title “All is forgiven.” The editors wrote that they had often been asked to publish other cartoons of Muhammad since then. “We always refuse to do it, not because it is prohibited – the law allows us to do it – but because we needed a good reason to do it, a reason that does teach and brings something to the debate,” they wrote.

Click here for Forbes India’s full coverage of the Covid-19 situation and its impact on life, business and the economy

© 2019 New York Times News Service