[ad_1]

Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary is fond of superlatives, which is why they were not lacking when he placed a $ 7 billion order for 75 737 Max aircraft from Boeing last week.

“This is not just a safe plane. . . It is the safest, most audited and most regulated aircraft ever delivered in the history of civil aviation, ”he declared, signing the largest firm order for the bad star passenger plane since it was grounded after two accidents. fatal 20 months ago.

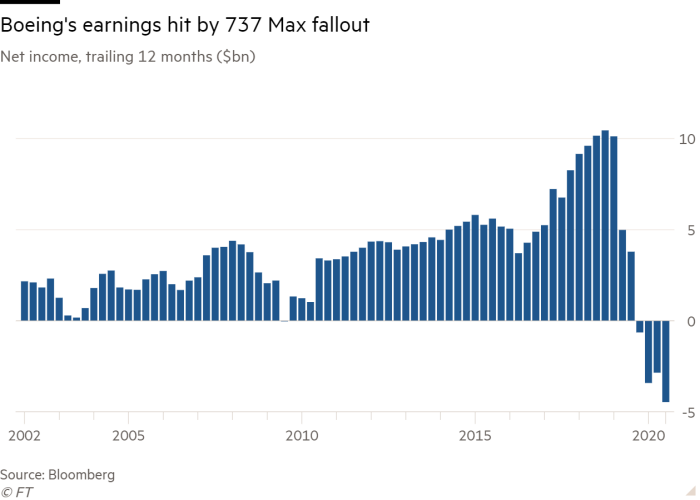

The deal was not the only good news for Boeing, whose credibility is at stake after flaws in the Max program led to the deaths of 346 people.

Safety regulators in the US have begun issuing the first certificates of airworthiness for individual aircraft, launching what is expected to be a steady return to service for more than 800 passenger aircraft that had been parked since authorities banned the flight of the Max in March 2019.

Gol, the Brazilian airline, told the Financial Times that “a very important milestone” had been passed, as it became the first airline to resume commercial 737 Max flights on Wednesday.

The return of the Max not only begins to close a terrible chapter in Boeing’s history, it reignites competition in the hottest segment of the aviation market. Boeing’s European rival Airbus has been virtually unchallenged in the single-aisle aircraft market since the Max was grounded.

“That’s important to the industry,” said Aengus Kelly, CEO of one of the world’s largest aircraft buyers, the finance leasing company AerCap. “We have to have competition. We cannot have a situation where one manufacturer has so much market share that the other is irrelevant. “

The aerospace supply chain also expects a boost from the rehabilitation of the Max, a major cash generator for many companies.

Clouds on the horizon

But the return to service of the Max and Ryanair order is just the beginning of a long journey for Boeing and the industry at large, which is struggling to overcome one of the worst aviation crises of modern times.

While big airlines like American Airlines are also expected to start carrying passengers in the Max this month, it will be some time before this translates into a flood of new orders from a global airline industry poised for net losses of $ 118k million this year and nearly $ 40 billion in 2021.

Since the Max was grounded, orders for about 1,000 of the airliners have been canceled or deemed too risky to include in Boeing’s order book of approximately 3,300 aircraft.

Brazilian airline Gol resumed Boeing 737 Max flights on Wednesday © Nelson Almeida / AFP / Getty

Even if passenger traffic begins to pick up next year after vaccine advances, airlines will have to deal with debt incurred during the crisis before they start buying in bulk.

Furthermore, there is little incentive for leasing companies, which accounted for about 40 percent of all aircraft purchases before the crisis, to buy the Max directly from Boeing when airlines are desperate to raise cash by selling and then renting planes.

“We are paying the airlines less than we would have paid for the plane that we canceled. It’s the airline that’s kidding me, ”a senior executive from one of the top 10 leases told the Financial Times.

A flawless re-entry

Meanwhile, Boeing’s priority is rebuilding passenger confidence through a flawless re-entry into service of the Max. The rate of return will be measured and Boeing employees will be available to prepare even airline-owned jets for commercial service.

“Boeing will want to be an important part of that process because they cannot afford to have problems,” said Phil Seymour, president of IBA, the aviation adviser. “Even something that isn’t tragic will hit social media.”

Boeing expects it to take about two years just to ship the 450 single-aisle jets it failed to deliver in the past 20 months. Another 387 sit in airline hangars and they too will have to go through extensive work.

Each of those jets will need to be taken out of storage, updated with new software to address the malfunction that caused the accidents, and check for any deterioration caused by months of inactivity.

Aircraft components that were stored in coastal areas may have suffered corrosion as a result of sea air, for example, while aircraft located in dry climates such as deserts may have problems with sand or sand.

Aircraft fuselages destined for Boeing’s 737 Max production facility are in storage © Nick Oxford / Reuters

United Airlines, which has 15 Max aircraft in its fleet, estimates that it takes more than 1,000 man-hours to prepare a single aircraft for commercial operation..

Ultimately, all planes will need to be inspected by safety regulators, as Boeing lost the right to self-certification after revelations that it misled regulators about the Max. This right can eventually be restored, if regulators trust Boeing’s processes.

Catch up with Airbus

The return of the Max will also affect Airbus, which has seen its share of the popular single-aisle segment grow by 60%.

Even before the Max was grounded, Airbus was receiving orders for its A320neo and A321 family of narrow-body aircraft at a faster rate than the 737 Max.

Now the shadow of a price war looms over the industry as Boeing seeks to find a home for the orphan aircraft in its hangars and avoid further cancellations.

Boeing and Airbus insist they will not be dragged into one. But industry executives speak of hearing about a deal of just $ 35 million for a 737 Max, against a list price of $ 121.6 million and a more normal median sales price of around $ 60 million.

Industry executives say Boeing should try to close the gulf that has emerged with Airbus. It’s not just about the success of the Max program – the company’s reputation and future as a commercial aircraft manufacturer is at stake.

“At the very least, they have to defend themselves and do whatever it takes to defend themselves because Airbus has had no competition in recent years,” Kelly said.

“Airlines make a decision on a narrow-body aircraft every 20 years. That makes it very difficult to regain market share. If you lose a customer, the next chance to change that customer is 15-20 years. “

Some analysts are pessimistic that Boeing could close the gap. Not only are customers looking for more capacity in their single aisle aircraft, they also want narrow-body aircraft with the most expensive wide-body range to help reduce operating costs. The Airbus A321, a larger and longer-range derivative of the A320neo, is a better fit than the Max, analysts say.

“Will Boeing ever catch up? No, ”said Ron Epstein, an aerospace analyst at Bank of America. “While the Max was being repaired, its competitor was putting the finishing touches on the 321XLR, a very capable long-range narrow-body aircraft. It’s more capable than anything Boeing has. ”

Boeing’s answer to the A321 is the larger Max 10, which will enter service in 2022. But with a shorter range than the latest A321 variants, many consider it less capable.

At the core of Boeing’s short-haul offering, the 170-190-seat Max 8 jet is “a wonderful airplane for what it does, but it’s an airplane,” Epstein said.

The danger of doing nothing

Boeing has no illusions about the challenges, but it remains true to its Max family. “We have the utmost faith in this product,” Boeing President and CEO Dave Calhoun said last week at the signing of the Ryanair order.

The American company is betting that even before a significant recovery in passenger traffic, airlines already operating older 737s will want to replace them with the greener Max 8.

“You can take any airline in the world and they have retired their oldest 737s earlier than planned,” said Boeing spokesman Gordon Johndroe. “These airlines will need planes to replace the retired planes and for eventual growth. They want the Max because it is cheaper to operate and it helps airlines meet their sustainability goals. “

But there are those who believe that there will be no change in the competitive landscape without a new single-aisle aircraft to take on the A321.

“We are addressing a tectonic shift in market share if Boeing does nothing,” said Richard Aboulafia, vice president of Teal Group, the aerospace consultancy. “The A321 is not the optimal version. His main virtue is that he is alone ”.

Yet with more than $ 60 billion in debt and any sustainable cash boost from the Max likely to be missing in two years, Boeing executives are wary of another gamble that could cost the company dearly.

The crash site of the Ethiopian Airlines Boeing 737 Max plane in March 2019 © Michael Tewelde / AFP / Getty

Engine technology is not at a stage where a new aircraft can claim a radical change in fuel economy. And there is concern that any talk of a new plane could ruin the success of the Max, now intricately tied to Boeing’s. “If Boeing announced a new single-aisle aircraft in the next two or three years, no one would buy the Max,” said a Boeing customer.

Boeing is expected to try to delay a new plane as long as possible, to allow technology and time to erase memories of the Max crisis. In the meantime, it will poll customers on what their needs might be when the market finally recovers from the pandemic.

“If anyone thinks they know what the market will be like and what airline customers will want a couple of years from now, they don’t know what they’re talking about,” said a Boeing executive. “The investigation continues, but we really have to get through the pandemic before making any final statements.”

Additional information from Bryan Harris in São Paulo and Claire Bushey in Chicago