[ad_1]

After a summer of relative freedom of movement, autumn has brought a significant increase in COVID-19 cases in many European countries. As the European Union unsuccessfully seeks a united path forward in its various jurisdictions, national and regional initiatives are trying to solve the enigma of how to contain and reverse the spread of the virus without having a significant impact on the economy.

Europe is not alone in its suffering: much of the Northern Hemisphere is grappling with rising infection rates as autumn turns into a long winter. In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has announced a month-long shutdown as cases surpass the 1 million mark; In the United States, a third wave of COVID is underway, with the country registering a dismal record of 100,000 new cases in a single day.

As French President Emmanuel Macron has admitted, the virus has spread across Europe “at a speed that not even the most pessimistic predictions anticipated.”

He has called his new lockdown proposals a “brutal” brake on the virus, but compared to the determined measures taken in Victoria, it is a half-measure that has little chance of eradicating or even suppressing the virus. Schools, stores, and many businesses outside the hospitality and entertainment sector will remain open; so will nursing homes. Travel to and from work will continue and exercise will also be allowed within one kilometer of the home for up to an hour.

Given the rebellious tone of contemporary politics in France, this is probably as far as Macron can go. It is uncertain whether the French public, already deeply divided, will accept the measures. His attempt to divert attention from the health crisis by opportunistically courting a culture war with the Muslim citizens of France and the rest of the Islamic world has already had devastating consequences.

Read more: For French Muslims, every terrorist attack raises questions about their allegiance to the republic

If it is up to the police to force compliance in the absence of good will, protests will break out quickly, as they have in the Czech Republic, where far-right elements posing as anti-mask protesters have clashed with police in the streets of Prague.

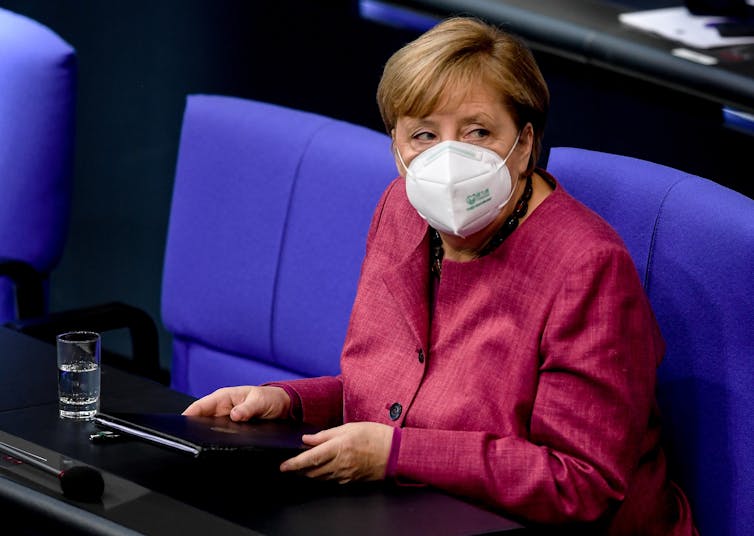

Germany, which had until recently escaped its neighbors’ higher infection rates, is now heading on the same path, too. Chancellor Angela Merkel warned Germans that the exponential growth in infections has left governments with no choice but to implement buffer measures as of November 2.

AAP / EPA / Filip Singer

These measures, described as a “soft lockdown”, like those proposed in France by Macron, prohibit visits to bars, restaurants, clubs and pubs, but allow schools, shops and places of worship to remain open.

Merkel has frankly confessed that she would have preferred to have taken these steps a fortnight ago, but felt they were simply politically unacceptable at the time. In his opinion, the delay was not ideal. “That is politics,” he admitted.

Your pessimism may be well founded. Many in Germany’s hospitality and entertainment industries already feel that, while much of society remains open, they have been forced to play the role of the slaughtered lamb.

On the noisy margins, Germany’s Querdenker movement, adjacent to Qanon, insists that any measure to prevent people from dying of COVID constitutes an egregious limitation on their personal freedom.

In typically opportunistic fashion, the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has also interrupted Merkel when she presented the measures to the Bundestag.

The party refused to support Merkel’s argument that only through “reason and social solidarity” can the virus be brought back under control. Instead, like right-wing populist elements around the world, they implausibly argue that Merkel is implementing a “dictatorship of the crown.”

AAP / EPA / Mattias Schrader

With the whole European project based on freedom of movement, something that was accentuated in the Brexit debates, the Australian approach of simply closing Europe’s internal borders, or even regional borders, has generally not been adopted.

Only Spain has moved quickly in this direction, halting domestic travel as part of its extension of “state of alarm” measures. In this case too, such measures have been met with protests.

As the state most committed to freedom of movement in the European Union, Germany has explicitly warned against such restrictions. Merkel told the EU:

… It is especially important for Germany as a country in the center of Europe that the borders remain open, that there is a functioning economic circulation and that we fight together against the pandemic.

However, it is unlikely that the EU can or will act when it comes to border closures, or even any other COVID measure.

The issue of mobility is a problem for the EU and the story is more misleading than enlightening. The Spanish flu model, which many are using to understand the current phases of the pandemic, is not appropriate. The Spanish flu was accelerated in part by the global movement of people that accompanied the demobilization at the end of the First World War. Unlike then, “returning to normality” today does not mean returning to a condition of global immobility. Now, especially in Europe, getting back to normal means going back to hypermobility.

Read more: The second wave of Europe is worse than the first. What went so wrong and what can you learn from countries like Vietnam?

In the absence of a vaccine, how societies respond to the virus and governments’ attempts to mitigate its effects will be of great importance. As elsewhere, in Europe the pandemic has tested the strength of social solidarity. If there is a strong social conviction that the health of the individual is best protected by preserving the health of all, then governments simply have to offer a set of guidelines on how to put this instinct into practice.

This was, to a certain extent, the experience of the first series of blockades in the European spring. This time, however, the extreme libertarian right is much more organized. They see any limitation on personal freedom to guarantee the safety of the community as an intolerable tyranny. Added to this is the fact that many Europeans are wary of their governments’ poor track record in promoting meaningful social cohesion.

Without community acceptance of government initiatives, the issue shifts from the desire of organizing communities to protect their vulnerable members to a police-led enforcement issue. It is potentially a direct and alienating approach that erodes any goodwill that remains.

Europe’s coming winter will test not only the resilience of its health system, but also the strength of its social fabric.