[ad_1]

In the early hours of February 1, 2021, the Burmese army, known as Tatmawdaw, arrested Aung San Suu Kyi and the leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in Myanmar’s capital Naypyitaw. That morning, the future that the people of Myanmar envisioned for themselves was gone. As historian and political commentator Thant Myint U has observed, the coup was supposed to be a conservative reboot of Myanmar politics, but instead ‘may have inadvertently ushered in a new revolutionary era […] The future of the country is at stake. ‘

Since the victory of the National League for Democracy’s free elections in 2015, which seemed to herald the country’s move towards democracy, artists in Myanmar have engaged in a Pavlovian struggle with self-censorship, conditioned by fear instilled for decades. military and state-sponsored dictatorship. suppression. In the pre-coup period, much of the art made in Myanmar was interchanged with typical landscapes and street scenes, and portraits of Aung San Suu Kyi, often painted in the same color spectrum that makes the country so photogenic. I opened an art space, Myanm / art, in 2016 to support a younger generation of artists trying to move beyond a politically obsessed national identity, looking at popular culture and global issues. However, the last two weeks have seen an incredible and immediate outpouring of protest art.

The symbol adopted a few days after the coup was the three-finger salute. An indirect loan from the hit Hollywood series The Hunger Games (2012-15), has become a rallying cry and an equalizer. Not only are millennial and Gen Z artists disenchanted by the country’s politics anymore, they are now directly affected, leading an online movement to advance the cause. Kyaw Htoo Bala, a 28-year-old art school graduate, caused a sensation by inviting dozens of artists to contribute their version of the greeting, breaking the habit of self-censorship and inspiring thousands of other teens and twentysomethings to speak up. out of.

Other artists have referred to much older symbols of resistance. Soe Yu Nwe, a ceramist from Yangon who studied at the Rhode Island School of Design, created a drawing – a colorful depiction of a swooping peacock, as if falling from the sky, losing its feathers in the process. The peacock is a powerful symbol in Myanmar, of royal lineage and freedom fighters. The bird is also the symbol of the Aung San Suu Kyi festival and refers to her arrest.

Ku Kue, the first female graffiti artist in Yangon and a talented graphic designer, has been more direct in her approach. His depiction of portraits of young people with the banner ‘You messed with the wrong generation’ is indicative of the anger and resentment felt by young people who have been given a taste of democracy, only to have it cruelly withdrawn. Thee Oo Thazin has gifted the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) with a collection of posters in both Burmese and English, with instructions for using your voice online, hitting pots and pans at night to show your dissent and support the protests. Bart Was Not Here creates artistic poster templates – one-word graffiti slogans that encourage people to ‘disobey’ or borrow rap lyrics to poke fun at the military in their bid for power. ‘You need us, we don’t need you’ is a work of art created to help move the CDM forward.

Artwork includes Burmese and English languages. English is familiar to younger generations, whose social media platforms and global pop culture exposure happily coincide with the well-known fact that top generals don’t speak English. Within days, the newly established Myanmar Contemporary Artists Association (AMCA) was on a Zoom call to discuss the best options to come together and create artwork on behalf of the cause. They set up what they call an artists’ street in front of the High Court in downtown Yangon, where they are painting on-site and selling artwork to support civil servants who have stopped working in support of the CDM. Artist Street also attracts musicians and performance artists; The entire block has become the newest exhibition space in the city. These first- and second-generation contemporary artists (born between 1960 and 1985) are more calculated in their practices, and their reactions to the military coup and its aftermath are sure to color their artwork for years to come. They are not among the keyboard warriors of a younger crowd, whose immediate anger and disgust at being silenced reverberates through their daily artwork shared online.

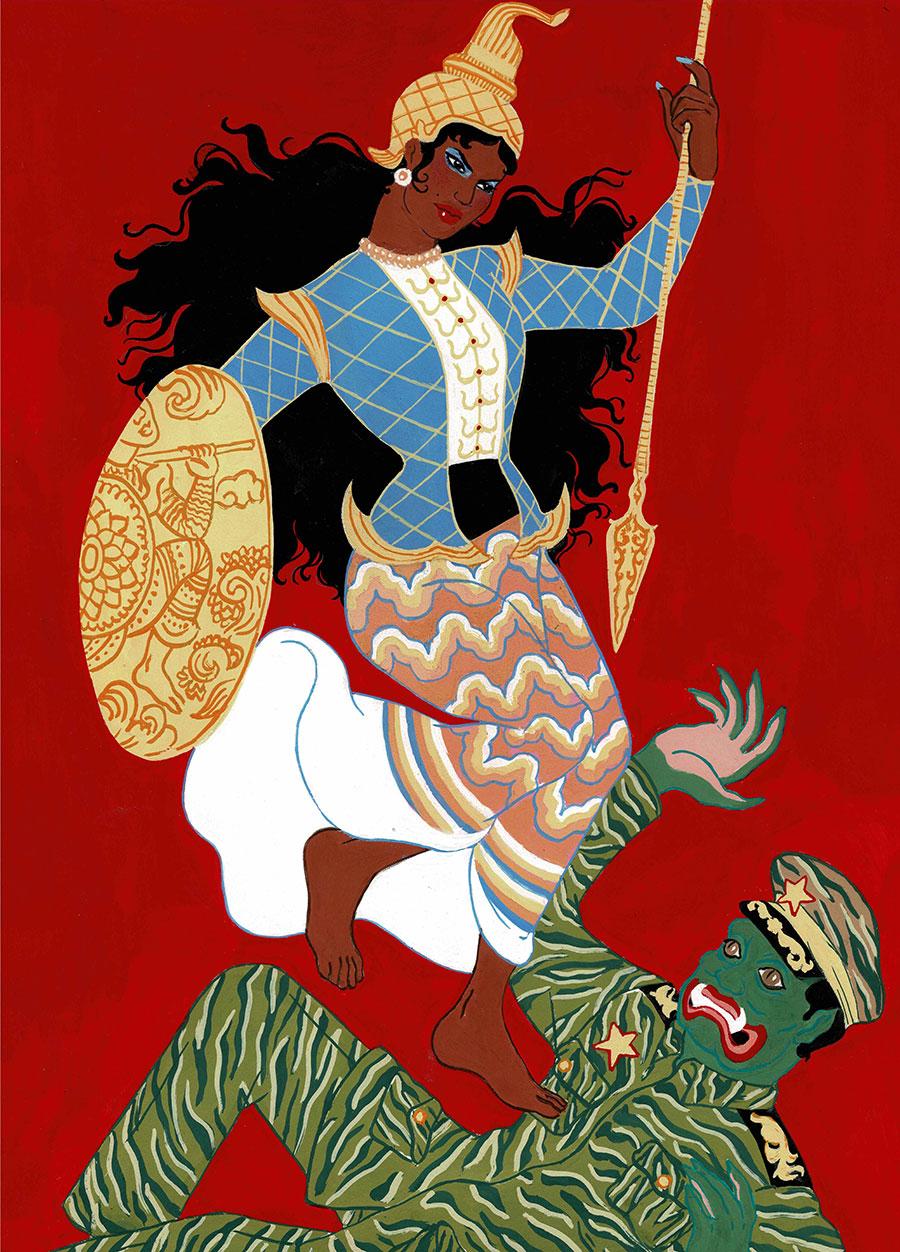

The last piece that caught my eye among the hundreds of works of art currently being shared in the name of dissent is that of Richie Htet. Known for his sultry portraits of mythological creatures from Buddhist and Hindu mythology wrapped in colorful textiles, Htet deliberated for a week before adding his own interpretation of the protest through his artwork. Dark-haired beauty ‘Mie Bamar Pyi’ is the national personification of Myanmar. With her spear and shield in hand, she is depicted descending on the Ogre, a common villain in Buddhist mythology, who is dressed in the clothing of a military general.

Lead image: Courtesy: Myanm / art, Myanmar