[ad_1]

Image copyright

Image copyright

fake pictures

The woman responsible for creating Mother’s Day, which was celebrated in many countries on the second Sunday in May, would have approved of the modest celebrations that are likely to take place this year. The day’s commercialization horrified her, to the point that she even campaigned for it to be rescinded.

When Elizabeth Burr received a phone call a few days ago from someone asking about her family history, she initially thought she had been scammed. “I thought, ‘OK, my identity has been stolen, I will never see my money again,'” she says.

In fact, the call came from a family history researcher looking for living relatives of Anna Jarvis, the woman who founded Mother’s Day in the United States more than a century ago.

Anna Jarvis was one of 13 children, of whom only four lived to adulthood. Her older brother was the only one to have children of their own, but many died young of tuberculosis and their last direct descendant died in the 1980s.

So MyHeritage’s Elizabeth Zetland decided to search for first cousins, and that was what led her to Elizabeth Burr.

When Elizabeth made sure her savings were safe, she gave MyHeritage the shocking news that her father and aunts had not celebrated Mother’s Day when they were growing up, out of respect for Anna, and her feeling that her idea it had been hijacked by degraded and commercial interests.

Anna Jarvis’ campaign for a special day to celebrate mothers was one she inherited from her own mother, Ann Reeves Jarvis.

Ms. Jarvis had spent her life mobilizing mothers to care for their children, says historian Katharine Antolini, and wanted the mothers’ work to be recognized. “I hope and pray that someone, at some point, will find a Mother’s Day to commemorate her for the unparalleled service she provides to humanity in all walks of life. She has a right to it,” said Ms. Jarvis. .

She was very active in the Methodist Episcopal Church, where, since 1858, she led the Mother’s Day Job Clubs to combat high infant and child mortality rates, primarily due to diseases that ravaged her community in Grafton, West Virginia.

Image copyright

fake pictures

Ann Reeves Jarvis

In work clubs, mothers learned about hygiene and sanitation, such as the vital importance of boiling clean water. Organizers provided sick families with medications and supplies and quarantined entire homes to prevent epidemics.

Ms. Jarvis herself lost nine children, including five during the American Civil War (1861-1865) who likely succumbed to the disease, says Antolini, a professor at West Virginia Wesleyan College.

When Mrs. Jarvis died in 1905, surrounded by her four surviving children, Anna, grief-stricken, promised to fulfill her mother’s dream, although her approach to Memorial Day was very different, says Antolini.

While Mrs. Jarvis wanted to celebrate the work done by mothers to improve the lives of others, Anna’s perspective was that of a devoted daughter. Her motto for Mother’s Day was “To the best mother who ever lived: her mother.” So the apostrophe had to be singular, not plural.

“Anna envisioned the vacation as a homecoming, a day to honor her mother, the only woman who dedicated her life to you,” says Antolini.

Mother’s Day or Mother’s Sunday?

- In the United Kingdom, the fourth Sunday of Lent has long been celebrated as Mother’s Sunday, originally a day when people who had left their home returned to their “mother church” and were reunited with their parents.

- In 1920, a Nottinghamshire woman, Constance Penswick Smith, launched a movement to revive the traditions of Mother’s Sunday, fearing that America’s secular Mother’s Day. USA It will move to Christian Mother Sunday.

- Anna Jarvis’ chosen day, the second Sunday in May, has been adopted by many countries, but a wide variety of other dates are also used around the world.

This message was something everyone could support, and it also appealed to churches: Anna’s decision to celebrate the holidays on a Sunday was a smart one, says Antolini.

Three years after the death of Mrs. Jarvis, the first Mother’s Day was celebrated at Andrews Methodist Church in Grafton: Anna Jarvis chose the second Sunday in May because it would always be around May 9, the day her mother was dead. Anna gave hundreds of white carnations, her mother’s favorite flower, to the mothers who attended.

The popularity of the celebration grew and grew: The Philadelphia Enquirer reports that soon it would not be able to “beg, borrow, or steal a carnation.” In 1910, Mother’s Day became a West Virginia state holiday and in 1914 it was designated a national holiday by President Woodrow Wilson.

A big factor in the success of the day was its commercial appeal. “Although Anna never wanted the day to be marketed, she did it very early. Therefore, the floral industry, the greeting card industry, and the candy industry deserve some credit for promoting the day,” says Antolini. .

Image copyright

fake pictures

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), American painter and illustrator, working on an official poster for Mother’s Day 1951

But this was not absolutely what Anna wanted.

When the price of carnations skyrocketed, he released a press release condemning the florists: “WHAT WILL YOU DO to defeat the charlatans, bandits, pirates, blackmailers, kidnappers and other termites who would undermine with their greed one of the finer, nobler and truer movements and celebrations? By 1920, he was urging people not to buy flowers at all.

She was upset with any organization that used her day for anything other than her original, sentimental design, says Antolini. This included charities that used the holiday to raise funds, even if they intended to help poor mothers.

“It was a day destined to celebrate mothers, not to feel sorry for them because they were poor,” explains Antolini. “Also, some charities were not using the money for poor mothers as they claimed.”

Mother’s Day was even drawn into the debate on women’s votes. Anti-suffragettes said a woman’s true place was in the home and that she was too busy as a wife and mother to get involved in politics. For their part, suffrage groups argue: “If she is good enough to be the mother of her children, she is good enough to vote.” And they highlighted the need for women to have a voice in the future well-being of their children.

Image copyright

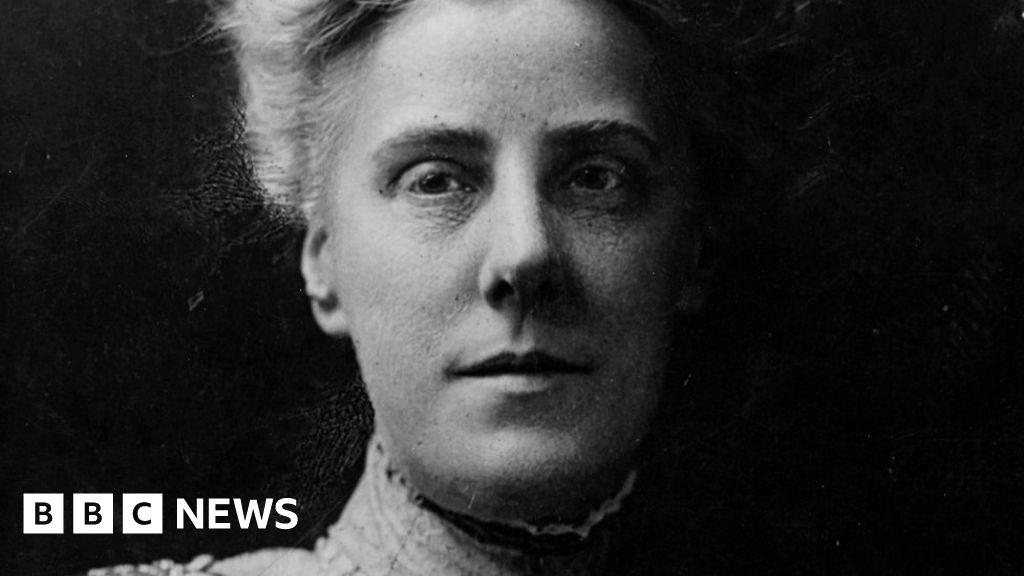

fake pictures

Anna Jarvis (1864-1948)

Apparently the only one who didn’t take advantage of Mother’s Day was Anna herself. She rejected the money that the florist industry offered her.

“She never benefited from the day and could have easily done it. I admire her for that,” says Antolini.

Anna and her visually impaired sister Lillian survived from the inheritance of her father and brother Claude, who ran a taxi business in Philadelphia before she died of a heart attack.

But Anna went on to spend every penny on Mother’s Day marketing.

Image copyright

Elizabeth Burr

Elizabeth Burr, MyHeritage cousin out of nowhere and her daughter Madison

Even before it became a national holiday, he had claimed copyright on the phrase “Second Sunday in May, Mother’s Day,” and threatened to sue anyone who marketed it without permission.

“Sometimes groups or industries deliberately use the plural possessive spelling ‘Mother’s Day’ to avoid Anna’s copyright claims,” says Antolini. A Newsweek article written in 1944 claimed that he had 33 pending lawsuits.

By then she was 80 years old and almost blind, deaf, and destitute, and was being cared for at a sanitarium in Philadelphia. It has long been claimed that the floral and card industries secretly paid for the care of Anna Jarvis, but Antolini has never been able to verify this. “I would like to think they did it, but it may be a good story and it is not true,” she says.

One of Anna’s final acts, while still living with her sister, was going door to door in Philadelphia asking for signatures to support an appeal to have Mother’s Day annulled. Once admitted to the sanitarium, Lillian soon died of carbon monoxide poisoning while trying to heat the ruined house. “The police claimed that the icicles were hanging from the ceiling because it was very cold,” says Antolini. Anna herself died of heart failure in November 1948.

Jane Unkefer, 86, another of Anna’s cousins (and Elizabeth Burr’s aunt), believes Anna Jarvis became obsessed with her anti-marketing crusade.

“I don’t think they were very wealthy, but she found all the money she had,” he says.

“It is embarrassing. I don’t want people to think that the family is not taking care of them, but it ended up in the equivalent of a poor man’s grave.”

They may not have been able to help her at the end of her life, but the family honored Anna’s memory in another way, by not celebrating Mother’s Day for several generations.

“We really didn’t like Mother’s Day,” says Jane Unkefer. “And the reason we didn’t do it is because my mother, as a child, had heard a lot of negative things about Mother’s Day. We recognized it as a good feeling, but we didn’t go to the fancy dinner or the bouquets “

Image copyright

Elizabeth Burr

Jane Unkefer (right), Emily d’Aulaire and Richard Talbott with their mother, Frances

When she was a young mother, Jane used to stop in front of a plaque in honor of Mother’s Day in Philadelphia and think of Anna. “It’s kind of a touching story because there is so much love in it,” says Jane. “And I think what came out of that was a nice thing. People remember their mother, just as she would have liked.”

Jane confesses that she has changed her mind about the celebration now. “Many generations later, I forgot all the negative things my mother said about it, and I am very angry if I don’t hear from my children. I want them to honor me and my day,” he says.

Jane’s younger sister Emily d’Aulaire has also found that her attitude towards Mother’s Day changes over time.

“I didn’t even know it until my own son was in school and came home with a gift for Mother’s Day,” she says. “Our mother used to say something like, ‘Every day is Mother’s Day.'”

For a long time, Emily was sad that Anna’s original intention for the day was thwarted, but these days she sends a card to her daughter-in-law, the mother of her grandchildren.

This year, many families will not be able to give flowers to their mothers or spend a day outside, but instead will celebrate Mother’s Day through a video link, due to the closure.

But Antolini believes that Anna and her mother would have been happy with such small celebrations. She imagines that Mrs. Jarvis, a veteran of many epidemics, would resurrect Mother’s Day Clubs to help others. And Anna would be delighted with the lack of shopping opportunities, which she felt clouded the purity of her original vision.

You may also be interested in:

Image copyright

Saint Louis / Ebony Art Museum

It’s been 50 years since photographer Moneta Sleet became the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize for journalism. Has your work received the recognition it deserves?

The great black photographer you’ve never heard of