[ad_1]

Mysterious and intense bursts of radio energy have been detected from within our own galaxy, astronomers have said.

Fast Radio Bursts, or FRBs, last only a fraction of a second, but they can be 100 million times more powerful than the Sun. Despite their intensity, their origin remains largely unknown.

Now, astronomers have been able to observe a fast radio burst in our own Milky Way for the first time. As well as being closer than any FRBs detected before, they could finally help solve the mystery of where they came from.

Scientists have had trouble tracking the origin of such explosions because they are so short, unpredictable, and originate far away. It’s clear that they must form in some of the most extreme conditions possible in the universe, with suggested explanations including everything from dying stars to alien technology.

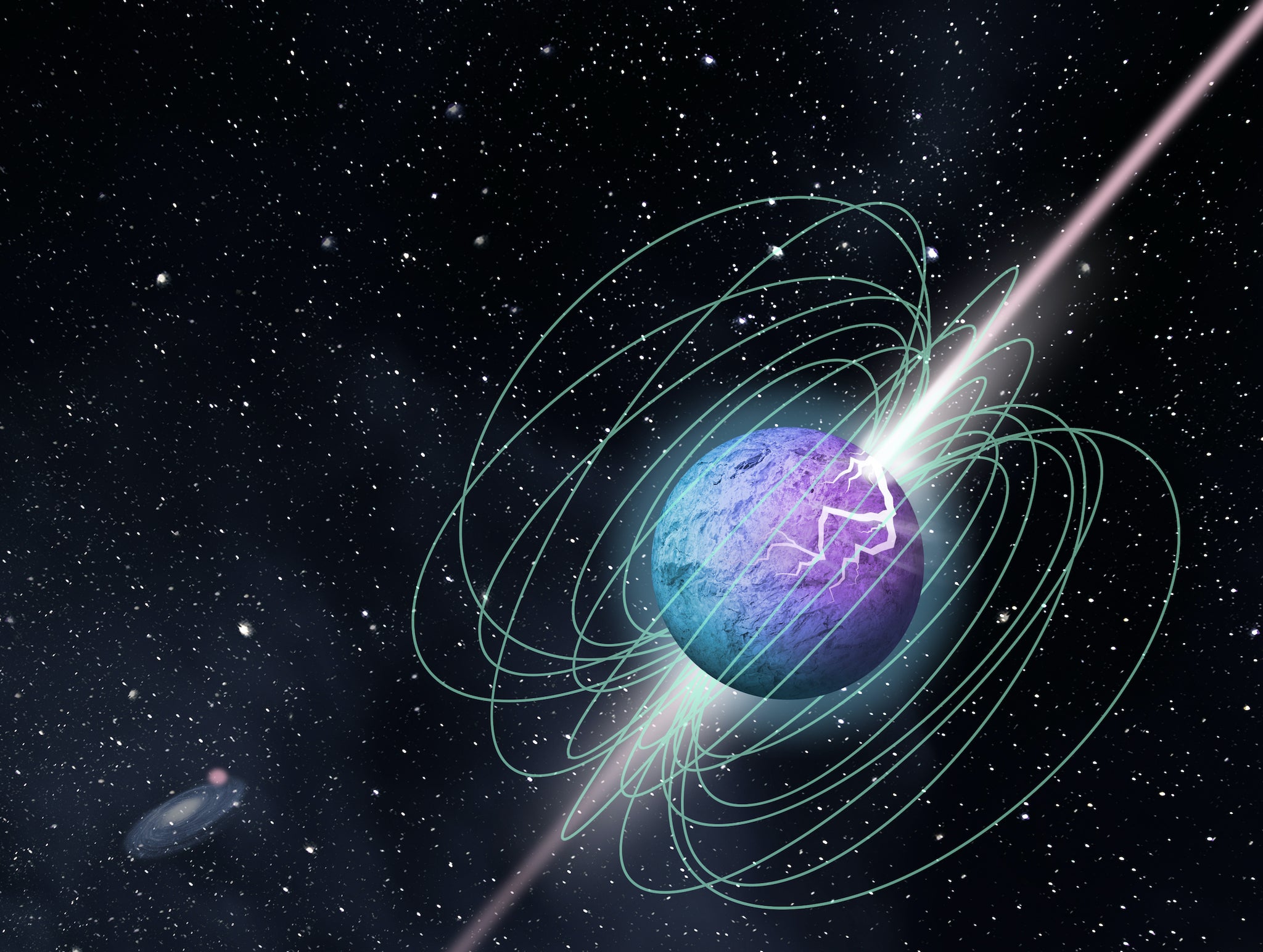

The radio energy bursts appear to come from a magnetar or star with a very powerful magnetic field, said the scientists who discovered the new FRBs. They were able to confirm that the explosion would look like the other more distant FRBs if observed from outside our own galaxy, suggesting that at least some of the other explosions could also be made up of similar objects elsewhere.

“There is a great mystery as to what would produce these large bursts of energy, which we have so far seen coming from half the universe,” said Kiyoshi Masui, an assistant professor of physics at MIT, who led the team’s analysis of brightness. “This is the first time that we have been able to link one of these fast alien radio bursts to a single astrophysical object.”

The detection began on April 27, when researchers using two space telescopes collected multiple X-ray and gamma-ray emissions from a magnetar at the other end of our galaxy. The next day, the researchers used two North American telescopes to observe that part of the sky and captured the explosion that became known as FRB 200428.

In addition to being the first FRB in the Milky Way and the first to associate with a magnetar, the explosion is the first to send out emissions other than radio waves.

The research is described in three articles published in the journal Nature today. It was based on data taken from telescopes around the world, with an international team of scientists using observations taken from teams in Canada, the United States, China, and space.

FRBs were first discovered in 2007, immediately sparking a flurry of speculation about what could cause such intense blasts of energy. Magnetars have emerged as the most likely candidate, especially given theoretical work suggesting that their magnetic fields could function as motors, driving powerful explosions.

To prove that, astronomers have tried to locate the origin of the explosions in as small parts of the sky as possible. In theory, that should allow them to associate them with known objects in space and look for associations between bursts of radio energy and other astronomical phenomena.

The new study is the first to do that work and to provide evidence linking FRBs to magnetars. At the very least, that could be a valuable clue to the origin of at least some of those FRBs.

“We calculated that such an intense explosion coming from another galaxy would be indistinguishable from some fast radio bursts, so this really lends weight to the theory that suggests that magnetars could be behind at least some FRBs,” said Pragya Chawla, one of the study’s co-authors and a PhD student in the McGill Department of Physics.

The new findings may not yet explain all known FRBs “given the large gaps in energy and activity between the brightest and most active FRB sources and what is being observed for magnetars, perhaps younger magnetars are needed, more energetic and active in explaining all FRB observations, “said Paul Scholz of the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Toronto.

If the FRB can be shown to come from a magnetar, many mysteries remain. Astronomers will have to look for the mechanism that allows the magnetar to power an FRB, seeking, for example, to understand how it could send out bursts of energy and such bright and unusual X-ray emissions at the same time.