[ad_1]

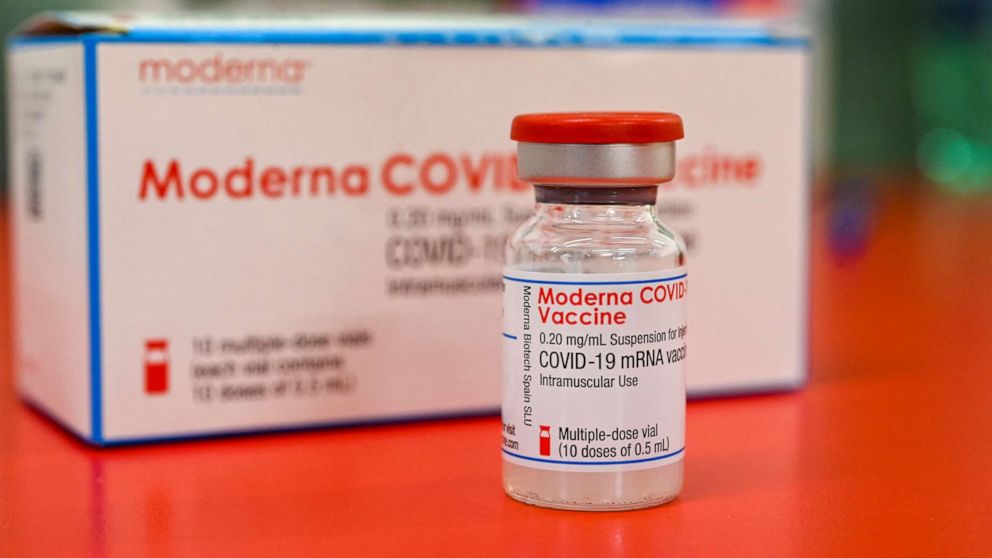

Moderna, Pfizer vaccines are based on state-of-the-art and highly adaptable mRNA technology.

As new variants of COVID 19 are spreading rapidly around the world, vaccine manufacturers are proactively finding ways to adapt to emerging threats.

Moderna announced Wednesday that it had dosed the first patient in a study to test a booster vaccine against one of the new variants.

New vaccines typically take many months to invent, develop, and refine. But the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are based on cutting-edge and highly adaptive mRNA technology, which can be quickly modified to keep up with the virus as it evolves.

These vaccines can be updated as “computer code, where they can be reprogrammed to handle the differences,” said Dr. John Brownstein, director of innovation at Boston Children’s Hospital and a contributor to ABC News.

A third vaccine, Johnson & Johnson’s single dose, based on a non-infectious viral vector, should also be relatively easy to update because it is also based on genetic material that can be modified.

But among all the vaccines currently available around the world, those that use mRNA may be the easiest to update against new variants, experts said.

Currently available COVID-19 vaccines are designed to target a specific portion of the virus, the so-called “spike” protein that helps the virus adhere to our cells. If a new variant develops mutations within that crucial spike protein, vaccines can be updated.

According to Pfizer and Moderna, modifications can be made in a few weeks. Based on laboratory experiments, it appears that their original vaccines will work just as well against almost all newly emerging COVID variants. Only one variant, the one that originated in South Africa, showed worrying signs that it could reduce the effectiveness of the vaccine.

For now, Moderna, Pfizer, and other companies are exploring updated booster injections against the South African variant as a precaution.

“Variants have not yet crossed the line,” said Dr. Paul Offit, professor of pediatrics in the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a member of the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory board.

“When that line is crossed, if that line is crossed, then I think we will have to think about a second generation vaccine that includes the variants,” he said.

Last month, the FDA updated its guidelines to give companies a clear path to follow on how to test a vaccine updates in a timely manner, still ensuring that booster vaccines are safe.

“Similar to what we do again with seasonal flu vaccines, we don’t have to have the same burden of proof for efficacy and safety to be able to release updated versions,” said Brownstein. In other words, people will not have to wait nearly a year for each new booster shot.

Future vaccines may offer unique protection against multiple variants. Moderna, for example, is developing a “multivalent” vaccine that will target the ancestral COVID strain and the new South African strain in a single injection.

But Brownstein said everyone is more likely to receive annual booster shots, modified if necessary to address whatever variant is circulating at the time, just like with the flu vaccine.

Sony Salzman of ABC News contributed to this report.

Abarna Ramanathan, MD, is a third-year internal medicine resident at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio and a contributor to the ABC Medical Unit.