[ad_1]

image copyrightAFP

In our series of letters from African journalists, Ismail Einashe considers the importance of memory for those who lose everything in the chaos of war.

Christmas Day, New Year’s Day and Valentine’s Day are dates when you will find many Somalis celebrating their birthdays. This is not as surprising as it sounds, it is just that very few Somalis know exactly when they were born and therefore go for more memorable dates.

Somalia has an oral culture – most Somalis are more likely to be able to tell you the names of the last 20 generations of their ancestors rather than the details of their date of birth.

And Somali only became a written language in 1972, when official records began to be kept, but very few remnants of these files because the country has been torn apart by civil war.

‘Dresden of Africa’

In fact, next year will mark three decades since the state of Somalia collapsed leaving many families like mine without their important documents or photos.

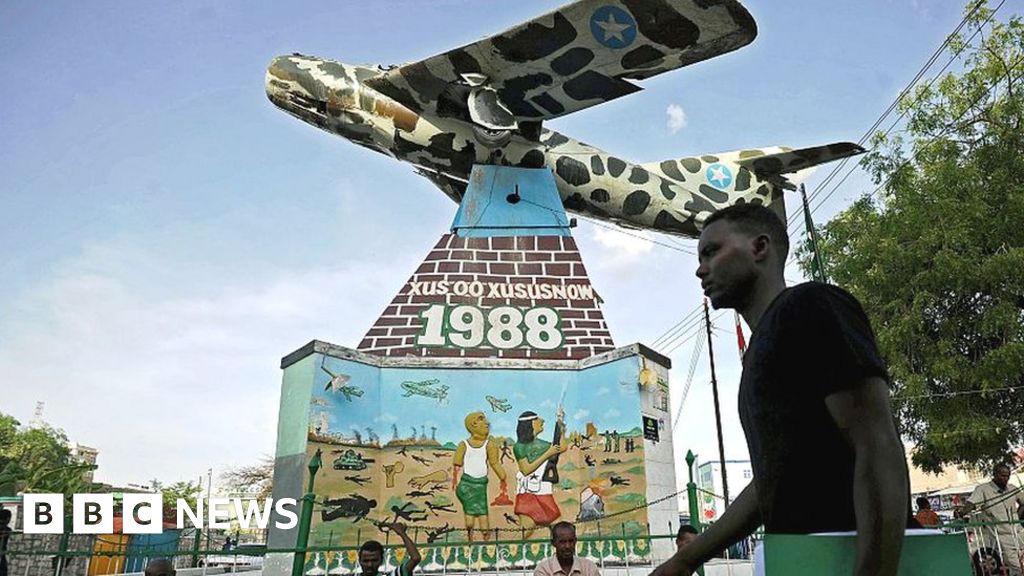

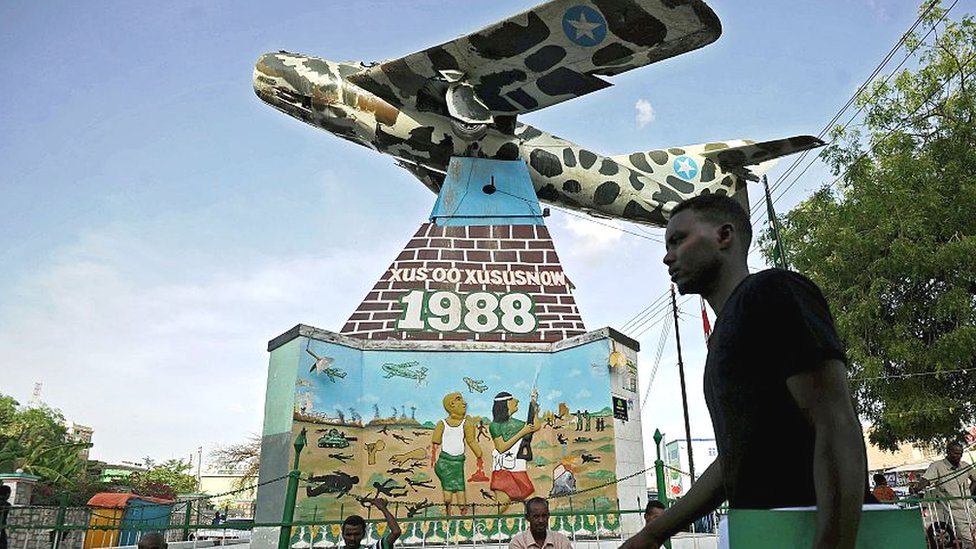

We were forced to flee the escalation of violence that began a few years earlier in 1988 with aerial bombardments and ground attacks by the regime of then-President Siad Barre.

Hargeisa, where I was born, became known as the “Dresden of Africa” as the city was completely devastated by the conflict.

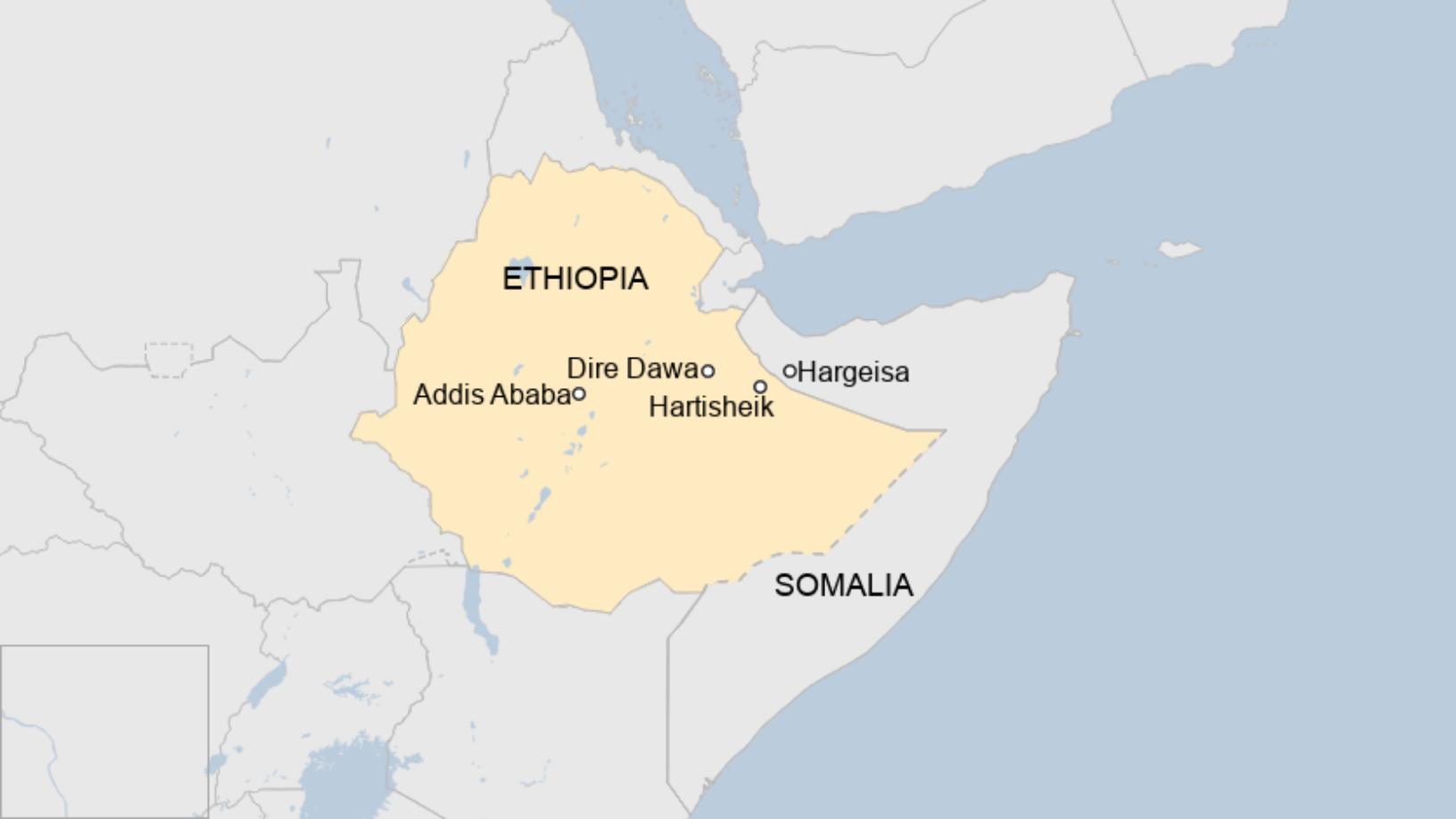

I spent my formative years living in what was then the largest refugee camp in the world: Hartisheik in Ethiopia, near the border with Somalia.

Like many of the thousands of people who passed through the camp, which finally closed in 2004, I was stripped of all my pre-war life records without a birth certificate or passport, relying only on fleeting and fleeting memories.

In search of these, I decided decades later to return to Hartisheik to see what was left of the camp that was once my home.

I wanted to try to get an idea of where I came from, to understand my position in this ever-changing world.

‘An endless Martian expanse’

One hot afternoon I took a flight east from Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa to Dire Dawa, the second largest city in the country, although it really felt more like a quaint and peaceful city with its beautiful old train station than It is no longer in use except as a home for a family of monkeys.

An old carriage lay outside the grand entrance where some men slept under the wheels, while others took refuge there from the sun chewing khat, drinking tea, and smoking cigarettes.

After leaving the refugee camp, I had briefly lived in Dire Dawa, so I visited my old places with interest before heading further east towards Hartisheik.

He was more nervous about taking that long trip in an old minibus. The situation was exacerbated by regular military checkpoints and several hours along a dilapidated road from the city of Jijiga to the border with Somalia.

I remembered the camp outside the city of Hartisheik as a dusty, remote and unforgiving place: an endless expanse with a cracked Martian hue.

You may also be interested in:

-

How London was sold to a boy fleeing the war

- ‘I stopped taking the train in Ethiopia’

When people arrived there 30-plus years ago, they encountered dire conditions: there was no shelter, water, food, or medicine, and countless people died of hunger, thirst and disease.

But the camp quickly grew into a city with a large market where you could buy all kinds of things and with places to sit and have tea.

People often think of refugee camps as just places full of misery and despair.

Yet as a child, I remember often having a lot of fun with my friends running around, playing with rocks, and screaming in dizzying excitement on the occasional UN plane that flew over us to deliver much-needed help.

However, the dust that was etched in my memory was not found on my return; I was dumbfounded to find a green, lush and beautiful landscape thanks to the rainy season.

No headstones for the dead

It seemed strange to me that such an attractive place with its ponds, trees and tall grass as far as the eye could see had been so full of people’s fears all those years.

I was somewhat disappointed in my memories.

There was nothing to mark the more than 600,000 refugees who once lived here at its peak, with no headstones for the dead and no official commemoration, the earth had claimed it all.

Kate stanworth

I saw an old Ethiopian man, Mohamed, who turned out to have once worked as a caretaker for the camp, a place he remembered full of the pain of war. “

Then I saw an old Ethiopian man, Mohamed, who turned out to have once worked as a caretaker for the camp, a place he remembered filled with the pain of war.

Now he lives with his family in a “toro”, a small traditional house and they have cows, goats and farm what little they can.

He told me that some buildings in the camp were still standing, including what could have been a hospital that a woman named Sahra showed me with her young granddaughter.

Painted appeared to be the UN colors of blue and white, there was a stench of decay and goat manure as it was occupied by animals belonging to the Sahra family, who once lived in Wajale on the Somali side of the border, but now grown here.

I thought of all those who must have lost their loved ones inside this building.

Of course, many of the younger people I came across, like the young cattle herder Jimale, had no memory of refugees at all.

I also met a group of Somali-speaking nomads who followed their camels in search of fresh grass and water, which they offered me, a weary traveler from London, fresh and spicy camel milk.

As the sky turned orange, I decided to return to the city of Hartisheik before the sun went down, leaving the camp for the second time, this time as a man, but a changed man slightly dazed and confused by the tricks of memory. .

It reminded me of another memory: I was about five years old and I found a small tub of discarded Vicks salve at camp, which I naively rubbed all over my face.

Inevitability ended up in my eyes and a fountain of tears rolled down my face as I ran dazed and confused through the camp in search of my mother.

More letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica

Related topics

-

Refugees and asylum seekers

- Somalia

- Ethiopia

- Refugee camps

[ad_2]