[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: Find the latest news and guidance on COVID-19 at Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

After a potentially more easily transmissible new genetic variant of SARS-CoV-2 was reported in the UK, several scientists have said that current vaccines are likely to protect against the new variant, and vaccine manufacturers are conducting tests to be sure.

But as a greater proportion of the world’s population becomes immune to SARS-CoV-2 through infection or vaccination, the virus is likely to evolve to escape that immunity, and vaccines may need to be updated, said Edward Holmes, PhD. Medscape Medical News.

“I can’t predict which mutations will appear, in what order and at what time, but I can make a pretty sure prediction that it will evolve and escape immunity as it always does,” said Holmes, an evolutionary virologist at the University of Sydney. Sydney, Australia, who participated in the mapping of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. “That is an inevitable consequence of natural selection. It has developed over millennia and will happen again.”

Research will show whether current vaccines are still highly effective against the recently reported variants. If so, “we can breathe a little sigh of relief,” Holmes told Medscape editor-in-chief Eric Topol, MD, head of the Scripps Institute for Translational Sciences in La Jolla, California, in an upcoming episode of One-on- An Interviews. Other virologists and vaccinologists they have tweeted in recent days they anticipate that the new variant is likely not different enough to make current vaccines ineffective.

New variant of an “endemic” virus

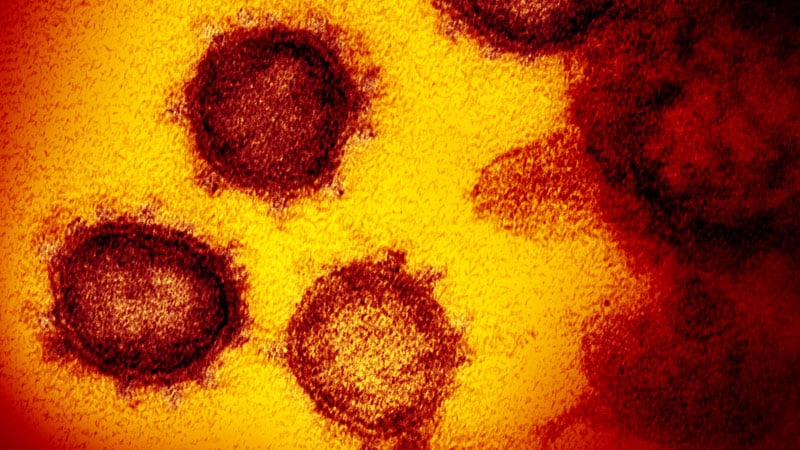

The British variant of SARS-CoV-2, called the B.1.1.7 lineage, has a host of genetic differences, particularly in the spike protein of the virus, according to the scientists who authored a preliminary genomic characterization of the variant. They identified three mutations with possible biological effects: N501Y, which changes an amino acid in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein; the deletion of two amino acids in the peak at sites 69-70; and another amino acid change, P681H.

The variant appears to be growing rapidly in the UK, Holmes said, because the new lineage is increasing in frequency compared to others. The same phenomenon appears to be occurring in South Africa, where a different genetic lineage is spreading with the N501Y mutation, Health Minister Zwelini Mkhize, MBCHB, announced on December 18.

There is evidence that viral loads are heavier in people infected with the UK variant, as indicated by lower average cycle threshold values for PCR tests and more sequence reads when samples are sequenced, he said. Holmes. This would explain the faster growth of the new variant.

Previous research has shown that the N501Y mutation in the spike protein is critical for host cell receptor binding. That mutation provides a molecular explanation for the higher viral loads seen in infected patients, Holmes said, but a full functional characterization of the biological implications of the multiple lineage mutations is yet to come.

One theory for how the new variant with so many mutations evolved is that a single person, perhaps immunosuppressed, had a partial immune response to a chronic infection that provided a unique set of selective pressures for the virus to evolve in an unusual way.

In the future, Holmes anticipates that SARS-CoV-2 will evolve in a more targeted fashion after more people become immune through infection or vaccination and it becomes more difficult for the virus to find a susceptible host. Only the fittest strain will make it through, and sprouts will likely become more seasonal, he said.

“I would bet money this is an endemic respiratory virus,” Holmes said. “Even if we implement the best vaccine coverage program ever, we will not vaccinate everyone … The virus will evolve fast enough to continue and people will re-enter the susceptible class.

“It is very likely that we will need to update these vaccines at some point,” Holmes predicted. “Maybe that will take 2 years, 5 years or 1 year.”

Vaccine monitoring and updating

If COVID-19 vaccines need to be updated in the future, it likely can be done without testing the new versions in additional large clinical trials of tens of thousands of people, Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for the Food and Drug Administration. US Medicines for Biologics Evaluation and Research, says in an upcoming Coronavirus episode in context with WebMD Medical Director John Whyte, MD, and Topol.

Upgrades to current vaccines could be made using the strain switch supplement paradigm developed for rapidly changing flu vaccines, Marks said. Early changes in the strain may require immunogenicity studies, requiring around 4000 participants, but later changes may not require further studies. “We will have a way to evolve here with these,” Marks said.

The question of how well current vaccines will deal with various SARS-CoV-2 mutations “keeps me awake at night,” Marks said. “You wonder where it will go now.”

Vaccine Manufacturers Testing

Moderna, which developed an mRNA-based vaccine in partnership with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is “actively examining all the mutant strains that are emerging,” said Chief Scientist Melissa Moore, PhD, at the Dec. 19 meeting. . of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The company tests whether sera collected during animal studies of the vaccine in rodents and non-human primates can neutralize new strains of SARS-CoV-2.

“So far, we’ve found that all the emerging strains that we’ve tested are neutralized by animal serum,” Moore said. The company will also test whether the sera of clinical trial participants neutralize emerging virus strains and will conduct deep sequencing studies of viruses causing any significant cases in clinical trial participants who received the vaccine to assess the mutations.

BioNTech CEO Ugur Sahin has said the company is confident that the mRNA-based vaccine it developed with Pfizer will be effective against the new variant of the virus, which it will investigate: “The likelihood that our vaccine will work,” he said, “It is relatively high.”

Kerry Dooley Young contributed reporting. Ellie Kincaid is the Associate Managing Editor for Medscape. Previously, he has written on healthcare for Forbes, the Wall Street Journal, and Nature Medicine. She can be reached by email at [email protected] and on Twitter @ellie_kincaid.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube, or send us a tip.

[ad_2]