[ad_1]

It’s about leveraging experience to respond more quickly to outbreaks by “turning to work together,” said Jean Patterson, CREID network’s senior program officer..

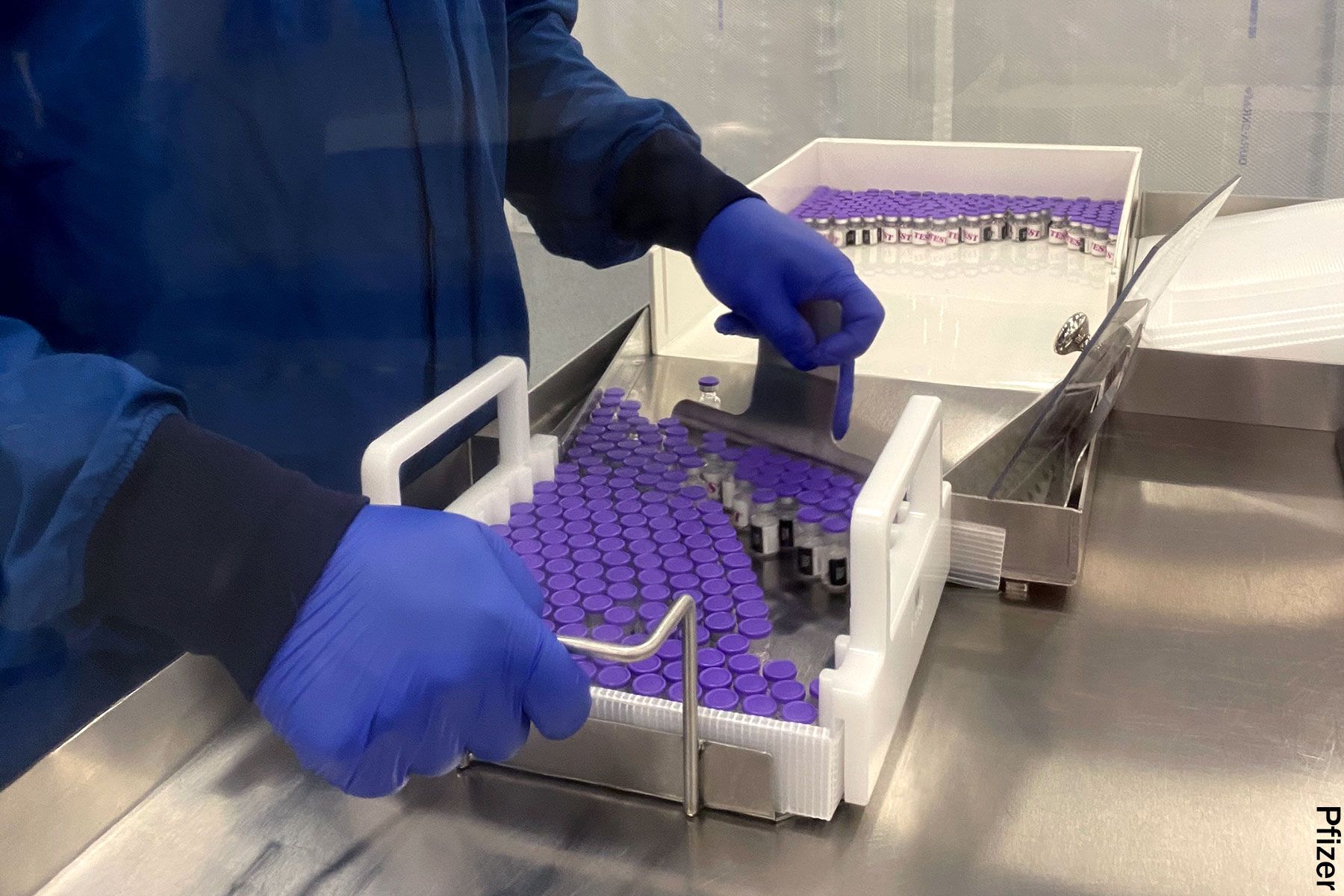

Researchers can use a prototype pathogen approach to study how and where infectious diseases emerge from wildlife to make the leap to people. With reports from 10 centers in the US and 28 other countries, scientists are developing families of vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics that can be identified and deployed faster the next time a “Pathogen X” is unleashed in the world. .

Krammer, who did not respond to requests for interviews, has speculated that new vaccines could be developed just 3 weeks after discovering a new virus and could be used immediately in a phase 3 trial, beating phase 1-2 trials. “Since a production correlation was determined for a closely related virus, the correlation can be used to measure the efficacy of the vaccine,” he writes.

Then the results of the clinical trial could be available about 3 months later. And while clinical trials are ongoing, production could increase globally and supply chains kick in early, so at that 3-month mark, the launch of the vaccine could begin immediately, he suggests.

New world records would be set. And in the event that the virus that emerges is identical or almost indistinguishable from one of the developed vaccines, existing stocks could already be used for phase 3 trials, which would buy even more time.

But how fast is too fast?

Wang, now a professor at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, says he is unsure whether conducting a series of phase 1 and 2 trials on related viruses would be enough to replace initial studies of a vaccine for a new pathogen.

Further investment in understanding the immune response to a wide range of viruses will help inform future vaccine development, but the proposed schedule for the phase 3 trial would be the best, he says. “And it depends largely on the infection rate at the sites selected for the vaccine studies,” he says. In the Oxford AstraZeneca studies, there were early concerns about whether there would be enough cases to collect evidence, given the low rate of infection in the UK during the summer.

“For a virus that spreads less efficiently than SARSCoV-2, it may take much longer for enough events to occur in the vaccine population to assess efficacy,” says Wang.

[ad_2]