[ad_1]

Does this mean that a vaccine will not protect against the virus either? Certainly not. First, it is not yet clear how common these reinfections are. More importantly, a weakened immune response to natural infection,

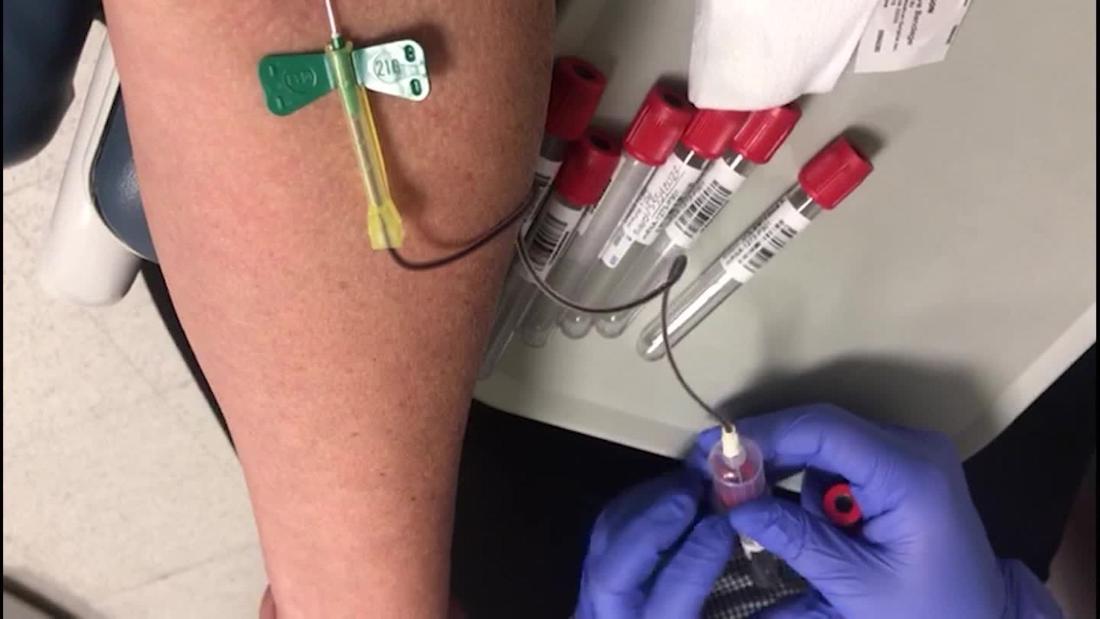

Any infection initially triggers a non-specific innate immune response, in which white blood cells trigger inflammation. This may be enough to eliminate the virus. But in longer infections, the adaptive immune system kicks in. Here, T and B cells recognize distinct structures (or antigens) derived from the virus. T cells can detect and destroy infected cells, while B cells produce antibodies that neutralize the virus.

During a primary infection, that is, the first time a person is infected with a particular virus, this adaptive immune response is delayed. It takes a few days before the immune cells that recognize the specific pathogen are activated and expand to control the infection.

Some of these T and B cells, called memory cells, persist long after the infection resolves. It is these memory cells that are crucial for long-term protection. In a subsequent infection by the same virus, memory cells are rapidly activated and induce a robust and specific response to block the infection.

A vaccine mimics this primary infection, providing antigens that prime the adaptive immune system and generating memory cells that can be rapidly activated in the event of an actual infection. However, since the antigens in the vaccine are derived from weakened or non-infectious material of the virus, there is little risk of serious infection.

Better immune response

Vaccines have other advantages over natural infections. For one thing, they can be designed to target the immune system against specific antigens that elicit better responses.

Natural immunity against HPV is especially weak, as the virus uses various tactics to evade the host’s immune system. Many viruses, including HPV, have proteins that block the immune response or simply stay low to avoid detection. In fact, a vaccine that provides accessible antigens in the absence of these other proteins may allow us to control the response in a way that a natural infection does not.

The immunogenicity of a vaccine, that is, its effectiveness in eliciting an immune response, can also be adjusted. Agents called adjuvants generally activate the immune response and can enhance the immunogenicity of the vaccine.

Along with this, the dose and route of administration can be controlled to stimulate appropriate immune responses in the correct places. Traditionally, vaccines are given by injection into the muscle, including for respiratory viruses like measles. In this case, the vaccine generates such a strong response that antibodies and immune cells reach the mucosal surfaces of the nose.

Understanding natural immunity is key

Maitreyi Shivkumar is Senior Lecturer in Molecular Biology at De Montfort University.

[ad_2]