[ad_1]

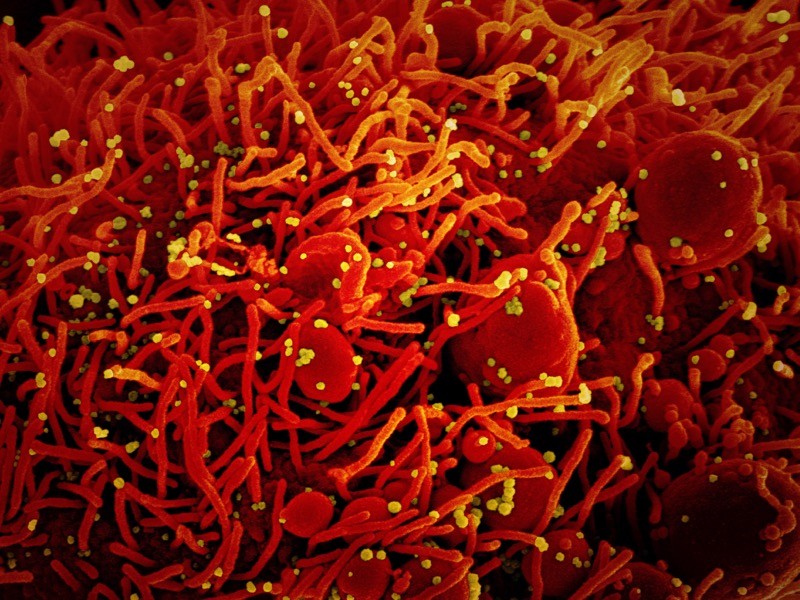

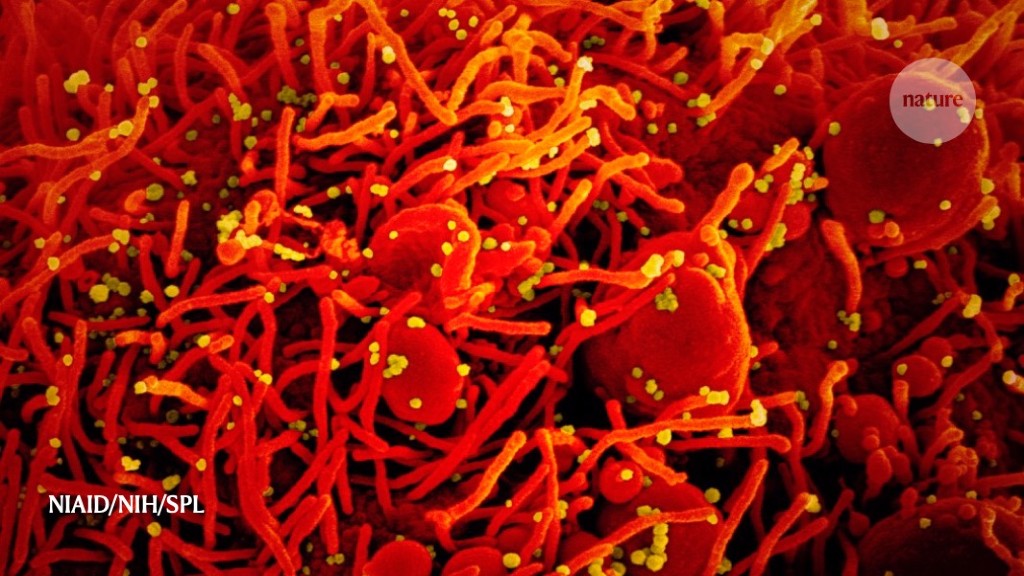

When it emerged last week that a man living in Hong Kong had been infected with the coronavirus again, months after recovering from a previous episode of COVID-19, immunologist Akiko Iwasaki had an unusual reaction. “I was really happy,” he says. “It’s a good textbook example of how the immune response should work.”

For Iwasaki, who has been studying immune responses to the SARS-CoV-2 virus at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, the case was encouraging because the second infection caused no symptoms. This, he says, suggested that the man’s immune system might have remembered his earlier encounter with the virus and jumped into action, fending off a repeat infection before it could do much harm.

But less than a week later, her mood changed. Public health workers in Nevada reported another reinfection, this time with more severe symptoms. Was it possible that the immune system had not only failed to protect against the virus, but had also made things worse? “The Nevada case didn’t make me happy,” says Iwasaki.

Bereavement anecdotes are common in the rocking world of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Iwasaki knows that he cannot draw firm conclusions about long-term immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 from a few cases. But in the coming weeks and months, Iwasaki and others hope to see more reports of reinfection, and over time, a picture could emerge of whether the world can rely on the immune system to end the pandemic.

As the data comes in, Nature reviews the key questions researchers are trying to answer about reinfection.

How common is reinfection?

Reports of possible reinfections have circulated for months, but the recent findings are the first to seemingly rule out the possibility that a second infection is simply a continuation of the first.

To establish that the two infections in each person were separate events, the Hong Kong and Nevada teams sequenced eachone,two the viral genomes of the first and second infections. They both found enough differences to convince them that separate variants of the virus were at work.

But, with just two examples, it is still unclear how often reinfections occur. And with 26 million known coronavirus infections worldwide so far, some reinfections might not be a cause for concern, says virologist Thomas Geisbert of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. We need a lot more information about how prevalent this is, he says.

That information could be on the horizon: time and resources are converging to make it possible to identify more cases of reinfection. It has been a long time since the first waves of infection in many countries. Some regions are experiencing new outbreaks, providing an opportunity for people to re-expose themselves to the virus. Testing has also become faster and more available. The Hong Kong man’s second infection, for example, occurred after he traveled to Spain and was tested for SARS-CoV-2 at the airport upon his return to Hong Kong.

Additionally, scientists at public health laboratories are beginning to rebound, says Mark Pandori, director of the Nevada State Public Health Laboratory in Reno, and an investigator on the Nevada study. During the first wave of the pandemic, it was hard to imagine tracking reinfections when testing labs were overwhelmed. Since then, Pandori says his lab has had time to breathe and to set up sequencing facilities that can rapidly sequence large numbers of viral genomes from positive tests for SARS-CoV-2.

All of these factors will make it easier to find and check for reinfections in the near future, says clinical microbiologist Kelvin To from the University of Hong Kong.

Are reinfections more or less serious than the first ones?

Unlike Iwasaki, virologist Jonathan Stoye of the Francis Crick Institute in London was not consoled by the lack of symptoms from the Hong Kong man’s second infection. Drawing conclusions from a single case is difficult, he says. “I’m not sure that really means anything.”

Stoye notes that the severity of COVID-19 varies enormously from person to person and can vary from infection to infection in the same person. Variables such as the initial dose of the virus, possible differences between SARS-CoV-2 variants, and changes in a person’s general health could affect the severity of a reinfection. “There are almost as many unknowns about reinfection as there were before this case,” she says.

Determining whether ‘immune memory’ affects symptoms during a second infection is crucial, particularly for vaccine development. If symptoms generally subside the second time, as in the Hong Kong man, that suggests that the immune system is responding as it should.

But if symptoms consistently worsen during a second COVID-19 episode, as it did in the person in Nevada, the immune system could be making things worse, says immunologist Gabrielle Belz of the University of Queensland and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical research in Victoria, Australia. For example, some cases of severe COVID-19 are made worse by dishonest immune responses that damage healthy tissue. People who have experienced this during a first infection may have immune cells that are primed to respond disproportionately again the second time, Belz says.

Another possibility is that the antibodies produced in response to SARS-CoV-2 help, rather than fight, the virus during a second infection. This phenomenon, called antibody-dependent enhancement, is rare, but researchers found worrying signs when trying to develop vaccines against related coronaviruses, responsible for severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome.

As researchers accumulate more examples of reinfection, they should be able to solve these possibilities, says virologist Yong Poovorawan of Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

What implications do reinfections have for the prospects for vaccination?

Historically, vaccines that have been easiest to make are against diseases in which the primary infection leads to long-lasting immunity, says Richard Malley, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts. Examples include measles and rubella.

But the ability to be reinfected does not mean that a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine cannot be effective, he adds. Some vaccines, for example, require “booster” shots to maintain protection. “It shouldn’t scare people,” says Malley. “It should not imply that a vaccine is not going to be developed or that a natural immunity to this virus cannot be produced, because we expect it with viruses.”

Learning more about reinfection could help researchers develop vaccines, Poovorawan says, teaching them what immune responses are important for maintaining immunity. For example, researchers may find that people become vulnerable to reinfection after antibodies drop below a certain level. Then they could design their vaccination strategies to take that into account, perhaps by using a booster shot to maintain that level of antibodies, Poovorawan says.

As public health officials grapple with the dizzying logistics of vaccinating the world’s population against SARS-CoV-2, a booster vaccine would hardly be good news, but it would not completely put long-term immunity against SARS out of reach. -CoV-2. says Malley.

Still, Malley worries that the vaccines may only reduce symptoms during a second infection, rather than prevent it entirely. This provides some benefit, but could effectively turn vaccinated individuals into asymptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2, putting vulnerable populations at risk. The elderly, for example, are among those most affected by COVID-19, but they do not tend to respond well to vaccines.

For this reason, Malley is eager to see data on how many viruses people ‘shed’ when they are reinfected with SARS-CoV-2. “They could still serve as an important repository for a future spread,” he says. “We need to understand that better after natural infection and vaccination if we want to get out of this mess.”