[ad_1]

In 2015, the Obama administration signed the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. USA (CSLCA, or H.R. 2262) in the law. This bill was intended to “facilitate a growth-friendly environment for the developing commercial space industry” by legalizing that US companies and citizens own and sell resources that they extract from asteroids and places outside the world (such as the Moon, Mars , or beyond).

On April 6, the Trump administration went one step further by signing an executive order that formally recognizes the rights of private interests to claim resources in space. This order, entitled “Fostering international support for the recovery and use of space resources,” effectively ends the decades-long debate that began with the signing of the Outer Space Treaty in 1967.

This order is based on both the CSLCA and Space Directive 1 (SD-1), which the Trump administration enacted on December 11, 2017. It states that “Americans should have the right to participate in commercial exploration, recovery and the use of resources in outer space, in accordance with applicable law, “and that the United States does not view space as a” global common good. “

This order puts an end to decades of ambiguity regarding commercial activities in space, which technically were not addressed by the Outer Space or Moon Treaties. The first, formally known as “The Treaty on the Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, was signed by the United States, the Soviet Union and the Kingdom Joined in 1967 at The Height of the Space Race.

The purpose of this was to provide a common framework that governed the activities of all the great powers in space. In addition to prohibiting the placement or testing of nuclear weapons in space, the Outer Space Treaty established that exploration and use of outer space would be carried out for the benefit “of all humanity”.

As of June 2019, the Treaty has been signed by no less than 109 countries, while 23 others have signed it but have not yet completed the ratification process. At the same time, there has been an ongoing debate on the full meaning and implications of the Treaty. Specifically, Article II of the Treaty establishes that:

“Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by use or occupation, or by any other means “.

Since the language is specific to national ownership, there has never been a legal consensus on whether the treaty’s prohibitions also apply to private appropriation. Because of this, there are those who argue that property rights should be recognized on the basis of jurisdiction rather than territorial sovereignty.

Attempts to address this ambiguity prompted the United Nations to draft the “Additional Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies”, also known as. “The Moon Treaty” or “Moon Agreement”. Like the Outer Space Treaty, this agreement stipulates that the Moon must be used for the benefit of all humanity and that non-scientific activities must be governed by an international framework.

However, to date, only 18 countries have ratified the Moon Treaty, which does not include the US. The US, Russia, or any other major power in space (except India). Furthermore, only 17 of the 95 member states that signed the Outer Space Treaty have become signatories to the Moon Treaty. This latest order, titled “Executive Order to Encourage International Support for the Recovery and Use of Space Resources,” addresses this same problem, stating:

“However, the uncertainty regarding the right to recover and use space resources, including the extension of the right to commercial recovery and the use of lunar resources, has discouraged some commercial entities to participate in this company. Questions about whether the 1979 Agreement governing the activities of States on the Moon and other celestial bodies (the “Moon Agreement”) establishes the legal framework for nation states regarding the recovery and use of resources This uncertainty has deepened, particularly because the United States has not signed or ratified the Moon Agreement. “

Management believes this act is complementary to SD-1, which emphasizes the importance of business partners in the Artemis Project and NASA’s plan to explore Mars and beyond. “The successful long-term exploration and scientific discovery of the Moon, Mars and other celestial bodies will require a partnership with commercial entities to recover and use resources, including water and certain minerals, in outer space,” states the directive.

After Artemis III achieves the long-awaited goal of sending the first astronauts to the Moon since the end of the Apollo era, NASA’s plans will shift toward the long-term goal of creating a “sustainable program” of lunar exploration. This will include the creation of the Moon Gate (an orbital habitat), as well as the Lunar Base Camp on the surface of the Moon.

These two habitats and research stations will allow long-term stays on the Moon, a wide range of scientific experiments, and even the ability to carry out refueling at the site. Combined with a reusable lunar lander, lunar rovers, and other non-expendable items, they will also facilitate regular moon missions and an overall cost reduction.

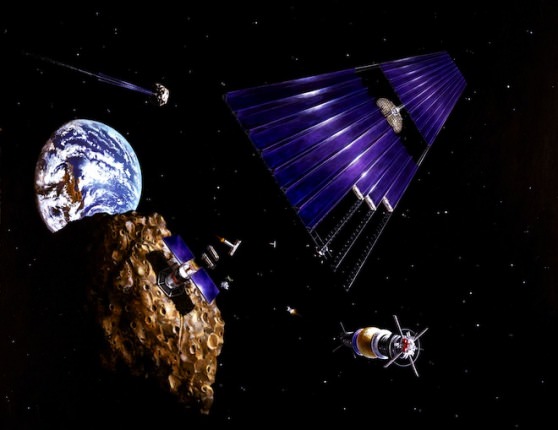

For years, search engines and space mining companies like Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries have been advocating for reforms that allow commercial exploitation of space. Similarly, people like Peter Diamandis (founder of X Prize and HeroX) and scientific communicator Neil DeGrasse Tyson have been saying for years that the first billionaires will make their fortune from asteroid mining.

BTW, NASA and HeroX recently launched the “Honey, I Shrunk NASA Payload” challenge, which offers $ 160,000 to the team that can find a solution to miniaturize payloads to the point that they are “similar in size to a new bar of soap ”- 100 x 100 x 50 mm (3.9 x 3.9 x 1.9 inches) and a weight of not more than 0.4 kg (0.8 lbs).

The purpose of this challenge is to significantly reduce the cost of sending payloads to the Moon in support of future lunar missions. However, there is also how you could enable a new generation of mini-rovers that would explore the lunar surface for resources. As indicated by the hosts on the challenge site:

“We need to develop practical and affordable ways to identify and use lunar resources, so that our astronaut crews can be more independent from Earth … Imagine a rover the size of your Roomba® crawling across the surface of the moon. These small rovers developed by NASA and its business partners provide greater mission flexibility and allow NASA to collect key information about the lunar surface. “

It is not hard to imagine that the miniature rover would also allow commercial entities the ability to explore asteroids and the lunar surface for resources that could be harvested and processed for export back to Earth. But not everyone is as excited about this recent move or the prospects it brings.

In fact, the Russian space agency (Roscosmos) officially condemned the executive order and compared it to colonialism. These sentiments were summed up in a statement issued by Sergey Saveliev, Deputy Director General for International Cooperation of Roscosmos:

“Attempts to expropriate outer space and aggressive plans to actually seize the territories of other planets hardly establish fruitful cooperation for countries (ongoing). There have already been examples in history when a country decided to start seizing territories. in your interest; everyone remembers what happened. ”

Saveliev is not alone in drawing parallels between the NewSpace industry (or Space Race 2.0) and the era of imperialism (ca. 18 to the 20th century). Last year, Dr. Victor Shammas of the Oslo Metropolitan University’s Research Institute of Labor and independent academic Tomas Holen produced a study that appeared in Palgrave Communications (a publication maintained by the magazine Nature)

Titled, “A giant leap for the capitalist class: private business in outer space,” Shammas and Holen claim that commercial exploitation of space will benefit humans disproportionately. At the center of this effort are Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and other Silicon Valley billionaires who, contrary to their humanistic claims, seek to expand their wealth while taking advantage of the fact that there is little or no oversight in this area.

“In this sense,” they wrote, “SpaceX and related companies are not very different from the maritime colonialists and merchant-exploiters of the British East India Company.” For the record, the East India Company operated with impunity in India while under British rule, making them the true governing authority over the nation and its people.

Could asteroid mining, lunar mining, and other worries outside the world become the new colonialism? Could various companies claiming bodies, planets, and moons trigger a period of conflict and a ruthless policy similar to that which existed during the 18th and early 20th centuries? Or could this be the beginning of “post-scarcity” for humanity and an economic revolution?

And is this condemnation of the Russian authorities merely an expression of regret that they do not feel well positioned to take advantage and that will change if the Russian equivalent of a musk or a bezo emerges? And what could we expect from countries like China and India that have been making significant progress in space for years?

All valid questions, and one that will have to be explored with greater energy and commitment now that the United States has officially declared that the Moon and space are “open for business.” It wouldn’t be surprising if certain quacks try to push the entire “buy land on the moon” scam more vigorously, too! Keep your eyes open people!

Further reading: Space.com, HeroX, Roscosmos