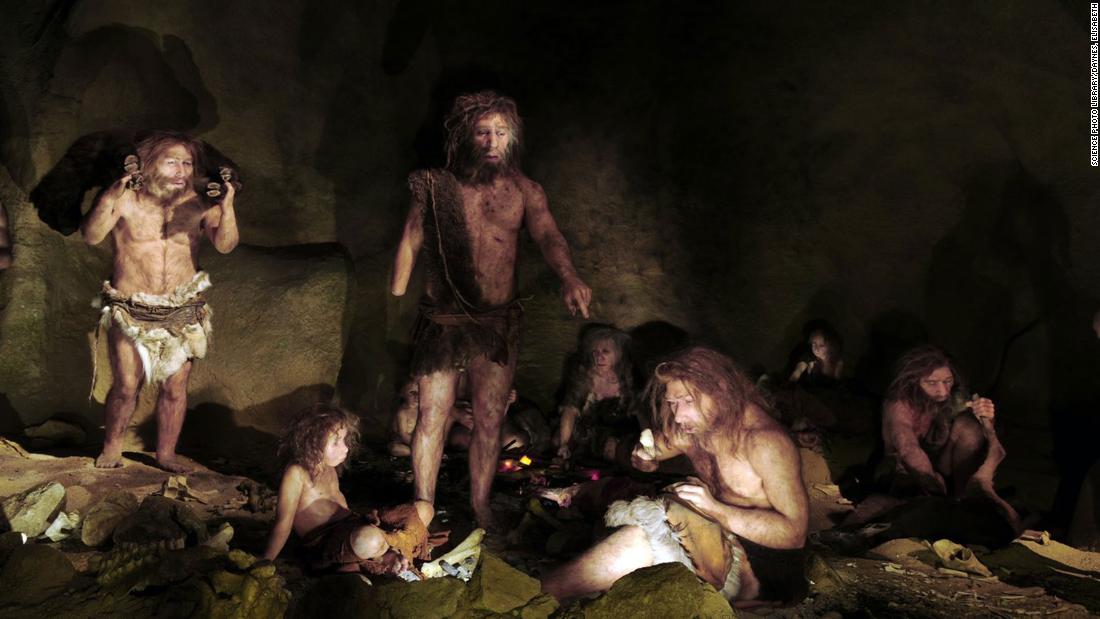

Many of us are part of Neanderthal, with our genes traces of past encounters between our earliest ancestors and the Stone Age hominids that populated Europe until about 40,000 years ago.

Now, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden think that we can also attribute our pain thresholds to our Neanderthal DNA.

The researchers studied pain questionnaires from more than 362,000 people in the UK.

The team then compared the responses to a person’s genetic profile and determined that people who had the Neanderthal variant of an ion channel experienced pain more often than those without. This channel passes ions, such as sodium or potassium, through the cell membrane, creating a current and allowing a cell to fire an electrical impulse or “pain signal.”

The most important factor in how much pain people report is their age. However, wearing the Neanderthal ion channel variant causes a person to experience more pain, similar to if they were eight years older, the researchers explained in an article published Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

“The Neanderthal variant of the ion channel brings three amino acid differences to the common ‘modern’ variant,” Hugo Zeberg, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the Karolinska Institute, said in a statement.

“While individual amino acid substitutions do not affect ion channel function, the full-length Neanderthal variant that carries three amino acid substitutions leads to increased pain sensitivity in people today.”

Zeberg told CNN that there were other variants in the ion channels that were not from Neanderthals, and not everyone with a low pain threshold could attribute it to a link to hominids.

Eventually, the discovery could help develop drugs, and patients would be offered accurate treatment plans based on their genetic variants, the researchers said.

“We all know that some people metabolize drugs quickly and others metabolize more slowly. I think that in the future, doctors will incorporate that kind of information into the patient one day,” Zeberg told CNN.

.