But experts aren’t terribly concerned about these antibody findings: They reject the suggestion that these initial data point to the risk of reinfection, and they reject claims that declining antibody immunity may end hopes of a long-lasting vaccine. For starters, our immune system it has other ways to fight infections besides antibodies. And even if our natural immune response is inferior, a vaccine would be designed to produce a better immune response than natural infection.

“The goal of a well-developed vaccine is to avoid these limitations [of natural infection] and optimize the vaccine in a way that ensures a robust and long-lasting immune response, “said Daniel Altmann, immunologist at Imperial College London.

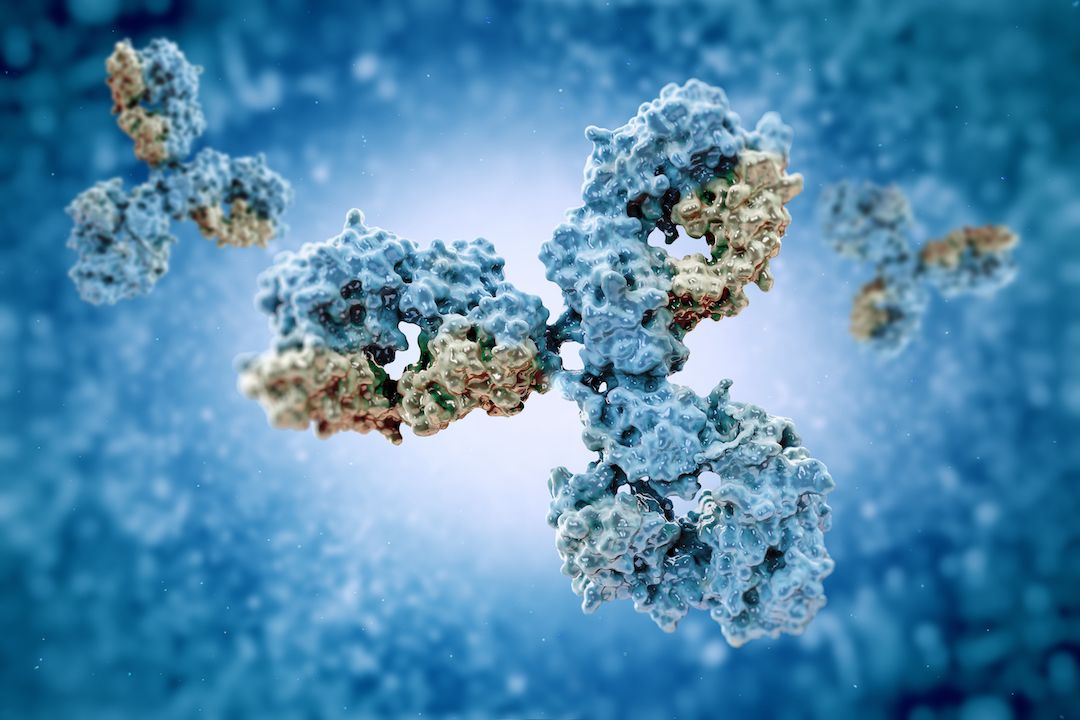

That’s not to say that recent research into lowering antibody levels in COVID-19 patients is not strong. The general principle of monitoring viral antibody levels to estimate immunity to a specific disease is well established. Antibodies recognizing and adhering to the shape of a part of a virus, either identifying it for subsequent destruction or neutralizing the pathogen on the spot. As long as a patient maintains a healthy number of antibodies to a given virus in their bloodstream, the body remains alert and ready to fight future infections. In general, vaccines work on the same principle, stimulating the immune system to make antibodies preventively.

Related: Here are the most promising coronavirus vaccine candidates out there.

“Scientists have been studying different antibodies for decades, and the methods of analyzing them are standardized,” said Lisa Butterfield, an immunologist at the University of California, San Francisco and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. “Once the specific tests for COVID-19 were developed, it was relatively easy to track antibody levels over time.”

Following these antibody levels in patients with COVID-19 has produced sobering results, at least at first glance. A preliminary study published on the prepress server medRxiv In mid-July, researchers at King’s College London found that people with mild infections had almost none of their hard-earned COVID-19 antibodies 60 days after infection. (That study has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.) And a recent letter sent to The New England Journal of Medicine Similarly, antibody levels decreased exponentially within 90 days of infection.

But these decreases in antibody counts may not be a cause for concern, from a clinical perspective. “The conclusions may be a bit far-fetched,” said Steven Varga, an immunologist at the University of Iowa. “We always want long-term, durable immune responses, but it is normal for many vaccines and pathogens to have a decrease in antibody titers [levels] overtime. I don’t think the drop in these posts is something to be terribly alarmed about. “

Also, how many antibodies are enough to prevent reinfection? “We don’t know yet,” Butterfield said. “Low levels of good neutralizing antibodies may be sufficient.”

Beyond antibodies

Antibody counts are also only a small part of the complex history of human immunity. White blood cells in the immune system fall into two categories: B cells, which make antibodies, and T cells, which bind to and kill infected cells. Both cells can live in the body for decades and increase in response to a disease the body has already encountered.

Decreased antibody levels may mean that B-cell immunity declines after a few weeks, but this does not necessarily mean that T-cell levels drop at comparable rates. In fact, a recent study in the magazine Nature It found that 23 patients who recovered from SARS, a close cousin of COVID-19, still had SARS-reactive T cells more than 15 years after the SARS outbreak (which ended in 2003). And a previous study published in medRxiv in June suggested that some patients without detectable antibodies still maintained T-cell immunity to the virus that causes COVID-19.

“The only catch,” Altmann warned, “is that we have never seen formal proof that T cells are functional alone. [without antibodies]. In the heat of battle, would T cells be enough to save you? “This is an important question because a robust immune response generally implies that T cells and B cells verify each other. But Altmann suspects that T cells are capable of preventing infection without B cell input.” I have seen examples of B-cell deficient patients who recovered from COVID-19 very well, “he said.” But the jury has yet to demonstrate that T-cells alone are protective. “

I’m still waiting for a vaccine

Regardless of what these declining antibody levels mean for general immunity, what the data certainly does not represent is a significant setback for any of the COVID-19 candidate vaccines . Even if we end up with a vaccine that produces antibodies that are shed after a few months, and even if the antibody counts are actually low enough to make patients vulnerable to infection, and even if T cells are not enough to fight the disease alone, an unlikely scenario: a short-term vaccine may still be enough to stop the pandemic.

“We don’t necessarily need twenty years of immunity to have an effective vaccine,” Varga said. “We need something that gives us short-term immunity, long enough for us to break this cycle of transmission.”

Even more promising, the more advanced candidate vaccines do not make use of killed or attenuated coronaviruses, which are at risk of producing disappointing immune responses similar to those seen in natural infections, Altmann said. Instead, pioneers like the Oxford or Moderna vaccines employ relatively new technologies . The Oxford vaccine uses a genetically modified version of a common cold virus (called an adenoviral vector) to transport genetic material from the new coronavirus; and the Modern vaccine uses messenger RNA (mRNA) to instruct cells to form a very small part of the new coronavirus.

Both methods can produce longer lasting immune responses than traditional whole virus vaccines, as they can be rapidly modified and tested in cells to produce a strong and long-lasting immune response. “Because you have designed this platform, you can optimize your immune response,” said Altmann.

No adenoviral or mRNA vaccine for human use is currently approved, but “I would be surprised if declining antibody levels were a problem” with these vaccines, Altmann said.

Originally published in Live Science.