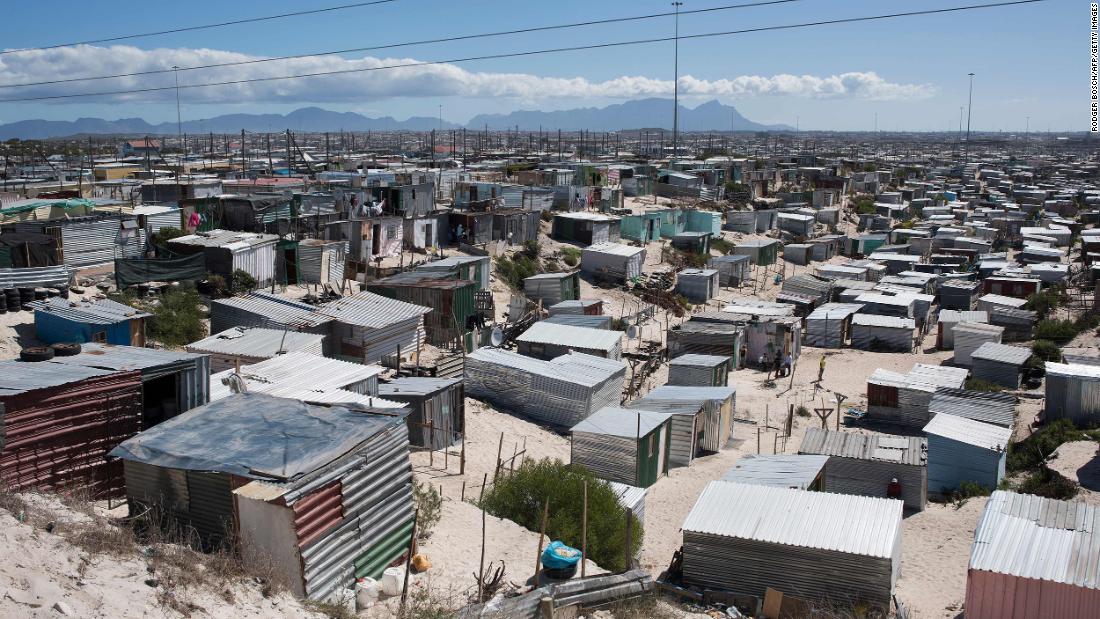

Crowded with more than half a million people, somewhere between the vineyards and beaches of this international destination, it is now the center of attention.

High-density areas like Khayelitsha are being closely watched because doctors say places like this are where the battle against Covid-19 on the African continent will be won or lost.

Western Cape is now halfway through the peak of its coronavirus surge. With more than 69,000 cases of Covid-19 and 2,066 deaths, according to government figures from July 5, it is the most affected province in the country.

“No one knew what the Covid epidemic would mean for South Africa. We had seen Covid traverse Europe, we saw what it was doing in the United States and everyone was terrified of what that would mean in South Africa,” says Dr. Claire Keene. , medical coordinator of the NGO Doctors Without Borders.

“We face so many failures with Covid. We have used the time well, but we always wonder if we use it enough,” he says.

In Khayelitsha, Doctors Without Borders, in association with the country’s health department, converted a basketball stadium into a field hospital to prepare for this increase. The scrub workers go out the back door and bring tanks from the forest of oxygen cylinders outside.

There are 70 beds and only a handful of empty spaces. The patients, most of them elderly, come from the immediate surrounding area, key to gaining trust in the local community. Some come out after a few days of steroid and oxygen treatment, while others are not so lucky.

Keene says his field hospital is at a low level of ICU care, but it is much more than a recovery room. It has become a critical way to lessen the burden on local hospitals as the peak increases.

But public health officials and doctors here acknowledge that their previous models, even those that took into account the aggressive shutdown, were too pessimistic.

Worst of cases

“We have fewer patients than we anticipated, we have less hospital admissions than we anticipated. And so far, we have had slightly fewer deaths than we anticipated,” says Professor Lee Wallis, Chief of Emergency Medicine at the Western Cape Government. .

However, Wallis and his team plan to have 1,400 additional beds ready for the worst-case scenario. He sits overlooking a still empty room in the huge reused convention center near Cape Town’s coastline. They expect the facility to be near capacity by the end of July.

Wallis says the burden of HIV has not had the impact that some feared. Much more critical, he says, are comorbidities like hypertension, obesity and diabetes that have also worsened the results for Covid-19 globally.

The pandemic hit South Africa later than Europe and North America, and experts here have had the benefit of learning from both the mistakes and the innovations of previous critical points.

Wallis says stopping putting patients on ventilators to give them high-volume oxygen made a difference almost overnight at major Western Cape hospitals.

Now, instead of being placed in a medically induced coma and breathing through a machine, many of the same type of patients are taking huge volumes of oxygen through masks or cannulas.

“We look at what is done in higher-income countries and adapt it to a lower-income environment and make it work,” he says.

While the peak in Cape Town is not as high as they expected, it believes the increase could last longer than anticipated by its previous models, even for many months, a situation that will stress both the health system and a population desperate for go back to some sort of normalcy.

Public health officials warn that it is too early to declare victory against the disease, and are wary of predictions about the virus being just over six months old.

Doctors and nurses in Cape Town still focus on one day and one patient at a time.

“Every death is heavy for healthcare workers, but when patients come breathless and leave, it is a tremendous achievement for everyone,” Keene says.

.