[ad_1]

Image copyright

Image copyright

Getty Images

Many scientists and historians believe that at that time a third of the world population (about 1.8 billion people) was infected with the “Spanish flu”.

If you have not heard of the Spanish flu before, this new crown crisis may have let you know that a deadly virus swept the world in the early 1900s.

People often call him “the mother of all pandemics”. According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the USA, between 1918 and 1920, the Spanish flu caused between 40 and 50 million deaths worldwide. Many scientists and historians believe that at that time a third of the world population (about 1.8 billion people) was infected with this virus.

Your computer does not support the playback of multimedia materials.

The epidemic began at the end of the First World War and caused more personnel losses than the First World War.

At a time when the world is in a crisis of new crowns, let’s take a look at the pandemic that once closed the world. What was the world after then?

In 1921, the world was very different.

Image copyright

Getty Images

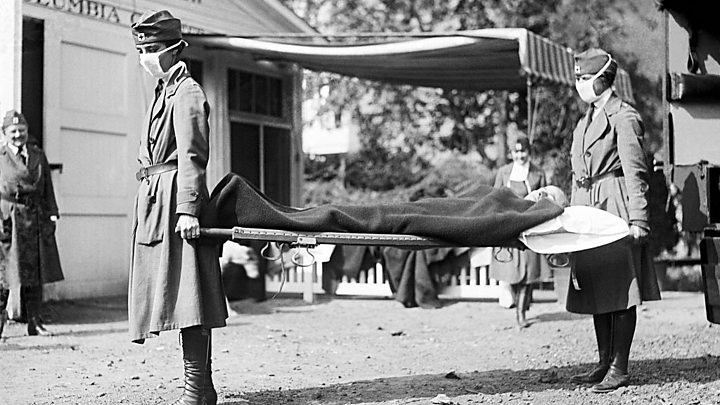

Medicine and science in 1918 were very limited compared to the current level of coping with the disease.

Medicine and science in 1918 were very limited compared to the current level of coping with the disease.

Doctors at the time knew that there were microorganisms behind the Spanish flu and knew that the disease could spread from person to person, but they still believed that the cause of the disease was bacteria, not viruses.

There are also limited treatments. The world’s first antibiotic was not discovered by humans until 1928, and the first flu vaccine was not put into public use in the 1940s.

It is especially important that the national health care system was not established at the time, even in countries with strong economic power, public health care remained a luxury.

“In industrialized countries, most doctors are independent portals or funded by charities or religious institutions, and many people do not have access to doctors,” said scientific writer Laura Spinney. She is also the author of “The Knight of Death: The Spanish Flu in 1918 and its Change in the World”.

Relatively young and poor

Image copyright

Getty Images

The Spanish flu attacked all humans in a very different way than the previous epidemic. The age of death cases is mainly between 20 and 40 years.

Previously, the flu between 1889 and 1890 killed more than 1 million people worldwide. But what is even worse is that the Spanish flu has attacked all of humanity in a very different way than the previous epidemic.

Most deaths are in the 20 to 40 age range, and men are particularly affected. Many people believe that the epidemic originated in the crowded military fields of the Western Front during World War I, and that the army began to spread after the war came home, which may also be the reason why men and young people are seriously affected.

The disease has also affected harder countries with weaker economic power.

A study led by Harvard academic Robert Barro in 2020 estimated that the Spanish flu caused 0.5% of deaths (approximately 550,000 people) in the United States at the time and 5.2% in India. The impact (nearly 17 million deaths).

The resulting economic impact is also enormous. Barrow and his team estimate that the pandemic reduced the gross domestic product (GDP) of all countries by an average of 6%.

“The casualties caused by World War I and the Spanish flu caused an economic disaster worldwide,” said Catharine Arnold, author of the “1918 Pandemic.”

Arnold’s grandparents were also killed in the UK by the flu.

“In many countries, there were no young men to continue running family businesses, running farms, receiving vocational and business training, getting married to raise children, and no one could make up for the loss of millions of lives,” said Arnold.

“Lack of the right men leads to the so-called ‘leftover women’ problem, and millions of women cannot find a suitable match.”

Women enter work

Image copyright

Getty Images

In the United States, the labor shortage caused by the flu and “World War I” paved the way for women to join the workforce.

The Spanish flu did not cause social changes like the Black Death in the 14th century (which led to the collapse of the feudal system), but it has shaken the gender balance in many countries.

Christine Blackburn, an academic at Texas A&M University, found that in the United States, the labor shortage caused by the flu and “World War I” paved the way for women to join the military.

“By 1920, (women) represented about 21% of the national workforce,” said Blackburn.

In the same year, the United States Congress passed the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which gave American women the right to vote.

“There is evidence that the 1918 flu has affected women’s rights in many countries,” she added.

Due to labor shortages, the wages of those employed at the time also increased.

According to data from the US government. Unit wages in the manufacturing sector were 21 cents in 1915 and increased to 56 cents in 1920.

Impact on the newborn

Image copyright

Getty Images

Studies in many countries have shown that babies born during a pandemic are more likely to get sick and less likely to be employed.

The scientists also studied babies born during the Spanish flu and found that they are more likely to have health problems, such as heart disease, than children born before or after the outbreak.

Analysis in the UK and Brazil shows that babies born between 1918 and 1919 are less likely to have a formal job or receive a college education.

Some theories say that the pressure on the mother during the pandemic affected the development of the fetus.

In analyzing the enlistment data of American soldiers born between 1915 and 1922, another clue emerged: “Class 1919” soldiers are approximately 1mm shorter than others.

Anti-colonialism and international cooperation.

Image copyright

Getty Images

After the 1918 pandemic struck India, nationalists began to speak.

By 1918, India had spent more than a century under British colonial rule.

The Spanish flu hit India in May of that year, and the Indians were more affected than the local British residents.

Statistics show that among low-caste Indians, 61.6 out of 1,000 people die from influenza, while among European residents, this figure is less than 9 out of 1,000 people.

Indian nationalists have always insisted that British settlers had mishandled the crisis. In 1919, Mahatma Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhi) published a number of “Young India” to fire on the British authorities.

Image copyright

Getty Images

A new epidemiological alert and control system was established after the 1918 pandemic.

“In the face of such a terrible and catastrophic epidemic, no government in any other civilized country will behave like an Indian government,” wrote one of the editorials.

Although “World War I” left the world with a geopolitical nightmare, the pandemic also highlighted the importance of international cooperation.

In 1923, the League of Nations, the predecessor of the United Nations, established the Health Organization. As a specialized agency, WHO created a new international infectious disease control system, led by medical professionals rather than diplomats, and operated in the same way as the International Bureau of Public Hygiene, which was already in existence at the time.

The World Health Organization was not established until 1948.

Public health progress

Image copyright

Getty Images

Many countries created or restructured the health sector in the 1920s.

The damage caused by the Spanish flu has contributed to the advancement of public health and, in fact, to the development of social medicine.

In 1920 Russia became the first country in the world to establish a fully public centralized health system. Other countries soon followed suit.

“Many countries created or remodeled the health sector in the 1920s,” wrote Laura Spinney.

“This is a direct result of the pandemic. Public health officials were completely excluded from the cabinet meeting during the pandemic or forced to request additional funding and jurisdictional support from other departments.”

Anthropologist Jennifer Cole of the Royal Holloway College at the University of London believes that pandemics and war have sown the welfare state in many parts of the world.

“The welfare provided by the state arose in this situation because large numbers of people have become widows, orphans and disabled people,” he explained.

Blocking and social distance also played a role

Image copyright

Getty Images

When the Spanish flu started to increase, two of the cities took completely different measures. A month later, more than 10,000 people in Philadelphia died from the disease, while the number of deaths in St. Louis is less than 700.

This is the story of the famous Twin Cities: In September 1918, the cities of the United States organized marches to promote the bonds of war, and the proceeds would be used for the war that was still ongoing.

When the Spanish flu started to increase, two of the cities took completely different measures: Philadelphia continued to implement the previous plan and San Luis decided to cancel the activity.

A month later, more than 10,000 people in Philadelphia died from the disease, while the number of deaths in St. Louis is less than 700.

This contrast becomes an example of support for social distance when it comes to infectious diseases.

An analysis of interventions in various cities in the USA. USA In 1918 he showed that in cities that banned public gatherings and closed theaters, schools, and churches early, the death rate was much lower.

A group of American economists from Princeton University also analyzed the closure measures of 1918. They found that cities with stricter measures recovered faster after the pandemic.

However, according to estimates, that pandemic still claimed the lives of almost 700,000 Americans. Harvard economist Robert Barrow said one of the reasons is that the blocking measures were launched prematurely.

“The policy usually lasted for approximately four weeks after the introduction of the policy, and then was released due to public pressure,” he said.

Barrow believes that if the block can last about 12 weeks, the result will be better.

“This is obviously an extremely relevant topic today,” he added.

Have you forgotten the pandemic?

Image copyright

Public domain

Edvard Munch’s “Self Portrait after the Spanish Flu” is a work that rarely mentions the 1918 pandemic.

Despite the lessons, in many ways, the Spanish flu is a forgotten pandemic.

Like the New Coronavirus, the outbreak also affected many celebrities: Former US President Woodrow Wilson and former British Prime Minister Lloyd George were ill the same year, former Brazilian President Rodríguez. Rodrigues Alves was also killed.

However, in public view, the “World War” covered the Spanish flu, in part because governments in several countries censored the media to prevent the media from reporting the impact of the flu during the war.

In addition to underreporting, this crisis has largely disappeared in history books and popular culture.

Image copyright

User information

Former Brazilian President Rodrigues Alves died of the Spanish flu.

“Even on the centennial of the pandemic (2018), a memorial to the Spanish flu cannot be found … there are very few headstones to commemorate the sacrifices of doctors and nurses at the time,” said medical historian Mark Hornis. Baum (Mark Honigsbaum) wrote.

“In past novels, songs, or works of art, you can’t find many works that describe the 1918 pandemic.”

The exception is “Edvard Munch’s Self-Portrait after the Spanish Flu.” The Norwegian painter created this work while suffering from this disease.

Hornisbaum also noted that the 1924 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica “did not even mention the pandemic in reviewing the” most memorable years “of the 20th century.” History books were only published in 1968.

This new crown epidemic has definitely refreshed people’s ideas.