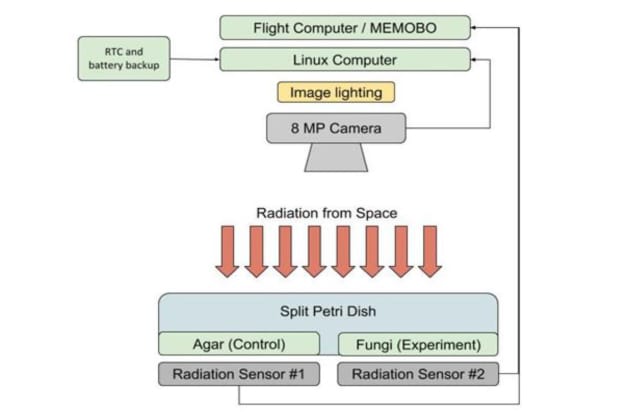

With that in mind, the research team decided to do a proof-of-concept study on the ISS to see how mold would fare in blocking space radiation. They installed Petri dishes with C. sphaerospermum Mushrooms on the one hand and a fungus-free control on the other. Beneath, a pair of radiation detectors were connected to the Raspberry Pi devices to capture radiation levels and measure humidity, temperature, flow, and other parameters.

Space Tango, Inc.

The fungi survived very well in the microgravity environment and reduced radiation levels by almost two percent. That could increase as much as five percent if the fungi completely surrounded an object, the team calculated. Considering the relatively thin 1.7mm mushroom “lawn” (layer) “this shows the ability to C. sphaerospermum to significantly protect against space radiation, “the team wrote in a preliminary research paper.

Extrapolating further, the team calculated that a 21-cm (8-inch) thick layer would “largely negate” the annual dose it would get on Mars compared to Earth, which is protected by our magnetic field. That would drop to just 3.5 inches or 9 cm when combined with Martian soil, also known as regolith.

A great advantage of this for interplanetary travel is that you would need to carry a small amount of mushrooms aboard a spaceship. Once on Mars, astronauts would simply add nutrients and convert them into the large amounts necessary to protect any base.

It will still be many years before we send astronauts to the red planet, but no less than three scouting missions, including two rovers, will be on the way in late July. With the launch of China’s Tianwen-1 last week, the next launch will be NASA’s Perseverance rover, complete with its own helicopter on July 30 (Thursday), so stay tuned for more coverage about it.