Super-muscular mice can now reveal to astronauts a way to save muscle and bone from being lost in space microgravity, a new study finds.

A major challenge for astronauts during long space missions is the simultaneous loss of bone and muscle, which is weakened and atrophy due to the Earth’s constant pulling out of gravity. Previous research has shown that in microgravity, astronauts can lose up to 20% of their muscle mass in less than two weeks.

When Lee and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins University helped discover myostatin, the team of Se-Jin Lee and Emily German-Lee thought they could find a way to fight bone and muscle loss, a protein that normally limits muscle growth. , In the 1990s.

Related: The human body in space: 6 strange facts

“At the time, we showed the mice in which we deleted the myostatin gene, there was a dramatic increase in muscle mass throughout the body, individual muscles doubled in size,” said Lee, now a geneticist at the Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine. Farmington, Connecticut, told Space.com. “This immediately suggests the possibility that blocking myostatin may be an effective strategy to combat muscle loss due to a variety of diseases. This possibility also suggests that this may be effective for astronauts during extended space travel.”

For the past 20 years, researchers have wanted to see what effect blocking myostatin would have on rats sent into space. “We finally got a chance to do that last year,” Lee said.

In December, scientists launched 40 rats from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center toward the International Space Station on SpaceX’s CRS-19 Cargo Response Services mission. “We were so impressed with the dedication, attention and enthusiasm that everyone brought to the project, and it was a privilege to have the opportunity to work with all of them,” Lee said.

Related: How spacefaring rats adapt to life in space (video)

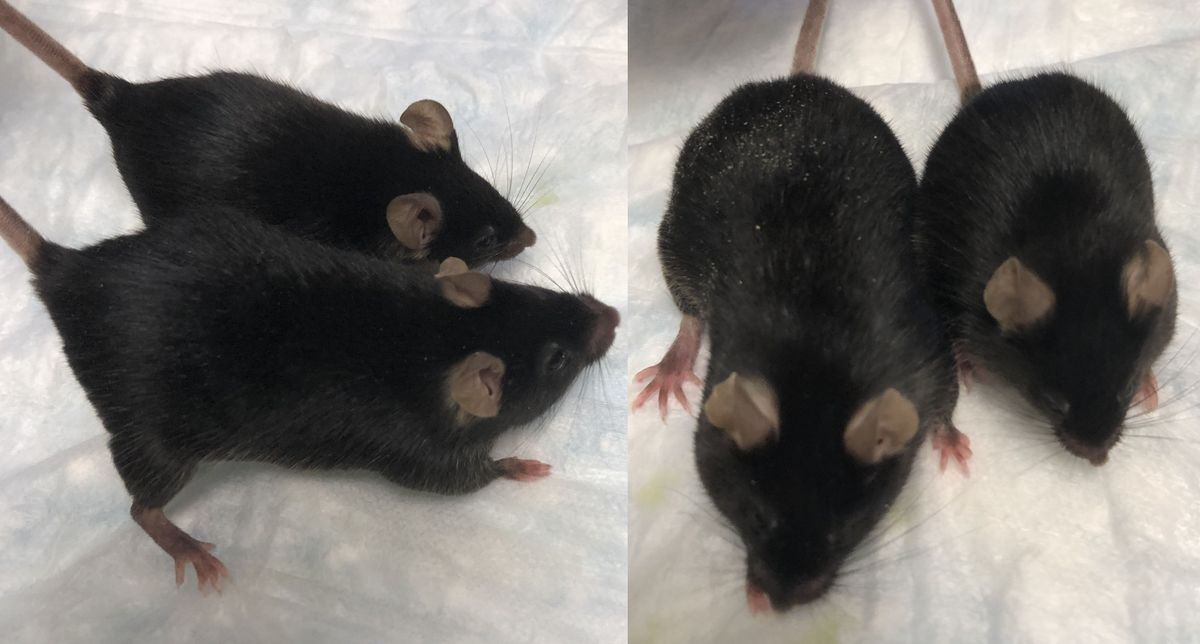

While 24 of the 40 rats were normal, eight of them were missing myostatin genes and eight others were treated by suppressing molecules of both proteins called myostatin and activin A, which have a similar effect on myostatin-like muscles.

Normal mice – those that have the myostatin gene and receive no protein-inhibitory treatment – have significant loss of muscle and bone during the 33 days spent in microgravity. In contrast, rats that were losing the myostatin gene and had twice as many muscles as a regular mouse, most likely retained their muscles during spaceflight.

In addition, scientists discovered a mouse that obtained a suppressing molecule of myostatin and activin, a dramatic increase in both muscle and bone mass. Moreover, rats treated with this molecule after returning to Earth experienced a greater recovery of muscle and bone mass than untreated rats.

These findings suggest that targeting myostatin and activin may be an effective therapeutic strategy to reduce muscle and bone loss in astronauts during extended spaceflight, as well as in those on Earth who are bedridden, wheelchair-bound. Bound or aged, ”German-Lee, a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington, told Space.com.

Related: Space travel causes joint problems in rats. But what about humans?

Although researchers find their results appealing, “it’s important to remember that these studies were performed with the help of mice,” Lee said. “Although mice have very similar physiology to humans, sometimes what we learn from mice does not translate exactly into humans. There is still a lot of work to be done to develop human treatments, but we believe this type of strategy holds great promise. Is. “

Lee, German-Lee and their colleagues detailed their findings on September 7 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Charles Q Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @speed.com and Facebook.