Tremor data from a 2016 earthquake near the South American and African tectonic plates, deep under the Atlantic Ocean, showed that the quake first moved to the northeast, then turned unexpectedly and hit the fault line back to the west, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience.

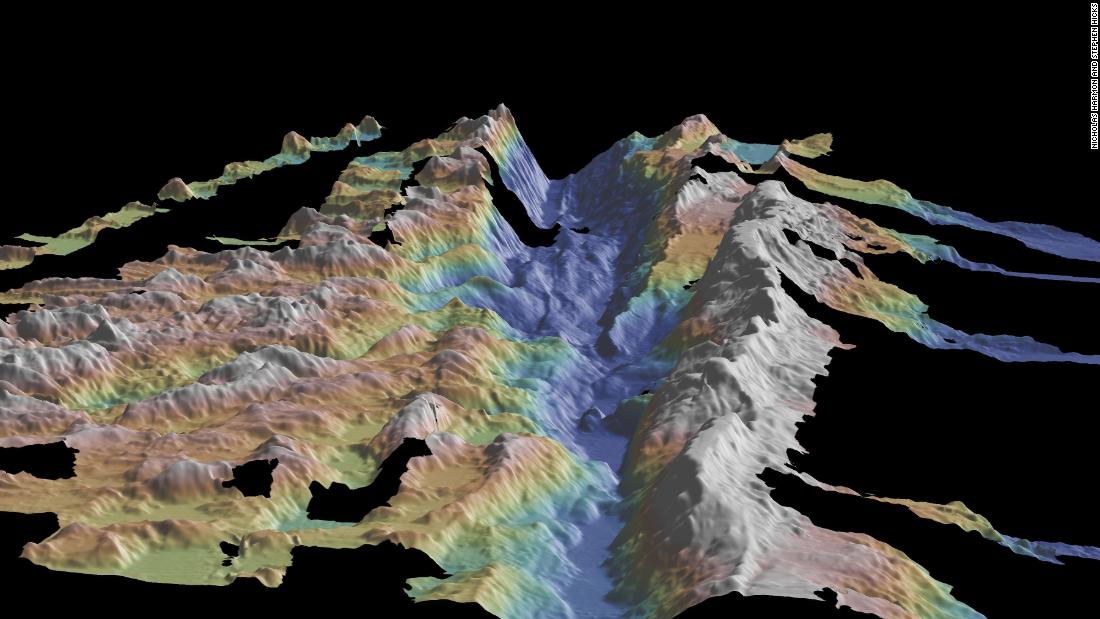

The episode, in an area known as the Romanesque Frache Zone, is visualized in this graphic animation from Imperial College London.

In addition to the initial discovery, the study informs how seismic events can move and change.

“Scientists and the people who use hazard maps both benefit from learning that earthquake failure has a wide variety of ways to explode than previously documented,” said John Vidale, a professor at the University of Southern California who was not associated with the study.

The so-called “boomerang earthquake” is perhaps one of the first of its kind.

“There are some hints that a small number of these reversible earthquake fractures appeared on land, but thorough evidence is too poor,” Hicks said, “so I think our study probably provides the clearest example of one to date.”

Double shakes could cause stronger tremors on land

Hicks warns that because evidence is so unfortunate, this finding does not mean that those living in the vicinity of earthquakes should be prepared for double earthquakes.

“We are not sure if what we have observed along a specific type of plateau boundary can also occur on different fault types on land,” he said.

Should this type of earthquake occur on land, Hicks said, it could cause stronger earthquakes, because the direction of an earthquake could affect its strength.

“Since we have only measured one of these types of earthquakes in detail, it will probably require more scientific analysis of other earthquakes before our result directly affects models of seismic hazard and their mitigation,” he said.

Documentation in the recent study of both a change in direction and faster velocity than expected velocity “challenges our ability to understand how friction works and also to anticipate shaking in future earthquakes,” Vidale said.

It is also significant that the study marks this shaking as moving at ‘supershear’ speeds.

.