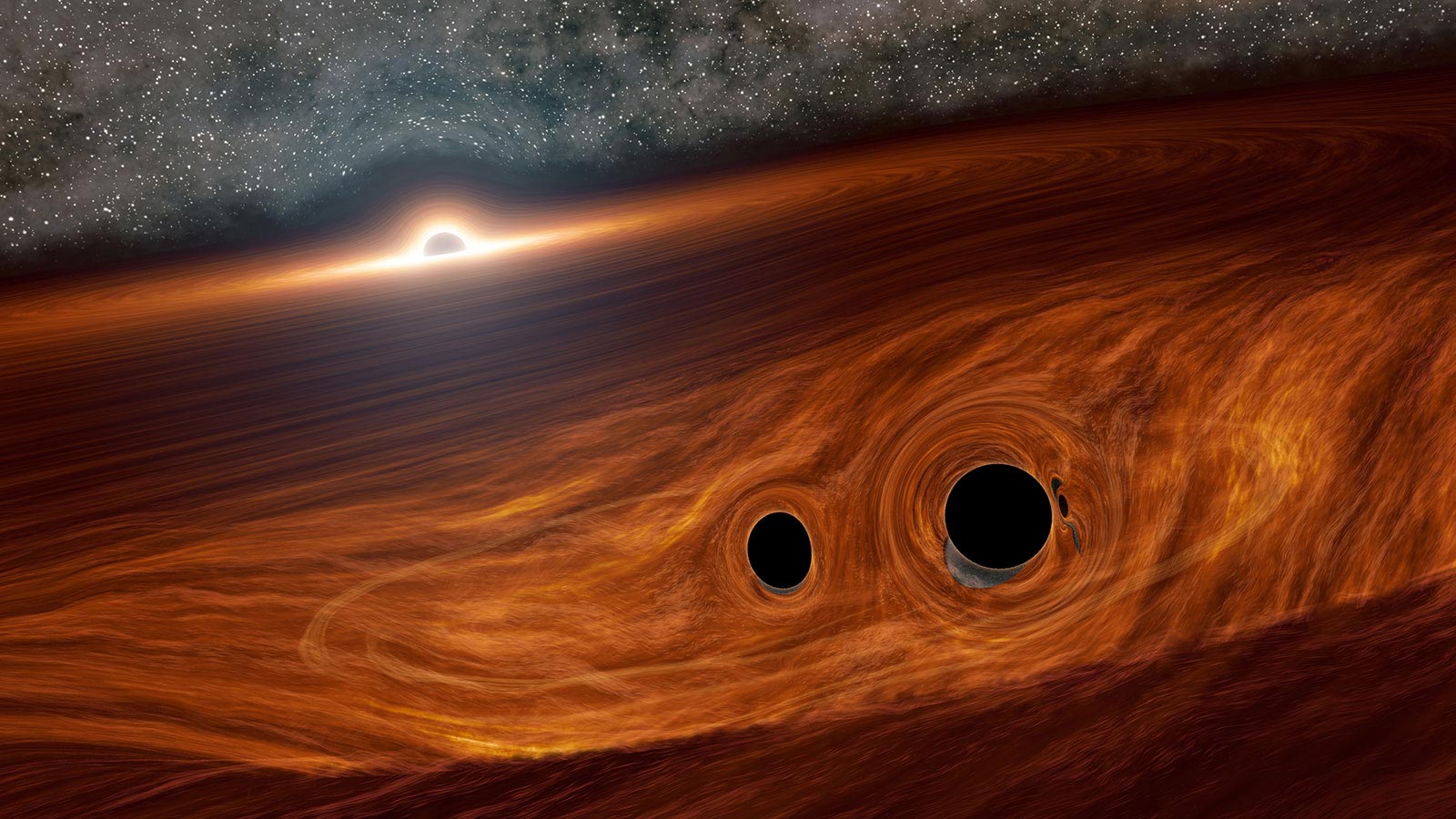

This artist’s concept shows a supermassive black hole surrounded by a disk of gas. Embedded in this disk are two smaller black holes that may have merged to form a new black hole. Image credit: Caltech / R. Daño (IPAC)

At first, astronomers may have seen the light of the merger of two black holes, providing opportunities to learn about these mysterious dark objects.

When two black holes spiral around each other and finally collide, they are sent gravitational waves – waves in space and time that can be detected with extremely sensitive instruments on Earth. From black holes and dungeon mergers are completely dark, these events are invisible to telescopes and other light detection instruments used by astronomers. However, theorists have put forward ideas on how a black hole fusion could produce a light signal by causing nearby material to radiate.

Now, scientists using Caltech’s Zwicky Transitional Facility (ZTF) located at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego may have discovered what such a scenario could be. If confirmed, it would be the first known flash of light from a pair of colliding black holes.

The merger was identified on May 21, 2019 by two gravitational wave detectors: the National Science Foundation Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the European Virgo detector, at an event called GW190521g. That detection allowed ZTF scientists to search for light signals from where the gravitational wave signal originated. These gravitational wave detectors have also detected mergers between dense cosmic objects called neutron stars, and astronomers have identified the light emissions from those collisions.

The ZTF results are described in a new study published in the journal Physical Review Letters. The authors hypothesize that the two associated black holes, each several dozen times more massive than the Sun, orbited a third supermassive black hole that is millions of times the mass of the Sun and is surrounded by a disk of gas and another material. When the two smaller black holes merged, they formed a new, larger black hole that would have experienced a kick and a shot in a random direction. According to the new study, it may have passed through the gas disk, causing it to light up.

“This detection is extremely exciting,” said Daniel Stern, co-author of the new study and an astrophysicist at POT‘Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which is a division of Caltech. “There is a lot we can learn about these two fused black holes and the environment they were in based on this signal that they inadvertently created.” Therefore, ZTF detection, along with what we can learn from gravitational waves, opens up a new avenue for studying both black hole fusions and these discs around supermassive black holes. “

The authors note that while they conclude that the flare detected by ZTF is likely the result of a merger of black holes, they cannot entirely rule out other possibilities.

Read Astronomers Find evidence of light exploded black hole collision to learn more about this research.

Reference: “Electromagnetic counterparty candidate to the binary black hole fusion gravitational wave event S190521g” by MJ Graham et al., June 25, 2020, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103 / PhysRevLett.124.251102