The WWDC20 master note produced by Apple did not directly emphasize this, but the new macOS Big Sur to be released to the public this fall is officially “macOS 11”, marking the end of the “Mac OS X” brand twenty-year progression. But don’t worry, it’s not the end of the Mac.

Up to 11

Apple’s first beta version of macOS Big Sur was made available to members of the developer program with the version designation “10.16,” which is what one might expect from Catalina’s successor Mac OS 10.15 last year. But Apple likes to change things and keep things interesting.

The Big Sur beta was originally called 10.16

In this case, the switch to macOS 11 was a subtle reveal. Speaking from the Steve Jobs Theater practice area during the WWDC20 keynote, Apple’s chief software officer Craig Federighi showed off screenshots indicating that the new release was finally overcoming the big “X” that has defined the Mac experience. for 20 years.

Apple’s new 2020 update of its human interface guidelines for developers now consistently refers to Big Sur as “macOS 11”, rather than just another incremental version of the “Mac OS X” brand that was first released as a beta public in 2000 and as initial “Mac OS X 10.0” public release in 2001.

Over the past two decades, Apple has released major new versions of its modern Mac operating system at regular intervals. Since 2016, it has emphasized the Roman number “X”, changing its business name to simply “macOS”. It has also increasingly capitalized on its “code name,” which changes annually, assigned to each release, first big cats, then places in California, relegating the actual version number more and more out of sight.

The move beyond “X” to 11 may seem unsettling, but it really only reflects a series of moves Apple has made to better align its work on the Mac desktop with its mobile platforms. After 14 years of iOS releases, we are now also getting a simple, Mac-optimized annual version number.

The Mac is not leaving, it is catching up

Several observers have suggested that Apple is losing its interest in the Mac platform, and fear that Apple is making plans to replace its conventional 35-year-old computing platform with, effectively, an expanded version of iPadOS. They cite developments like Catalyst, which helps developers bring their existing operating system code to the Mac, or the new switch to Apple Silicon Macs, which will allow future hardware to run iOS software without modification.

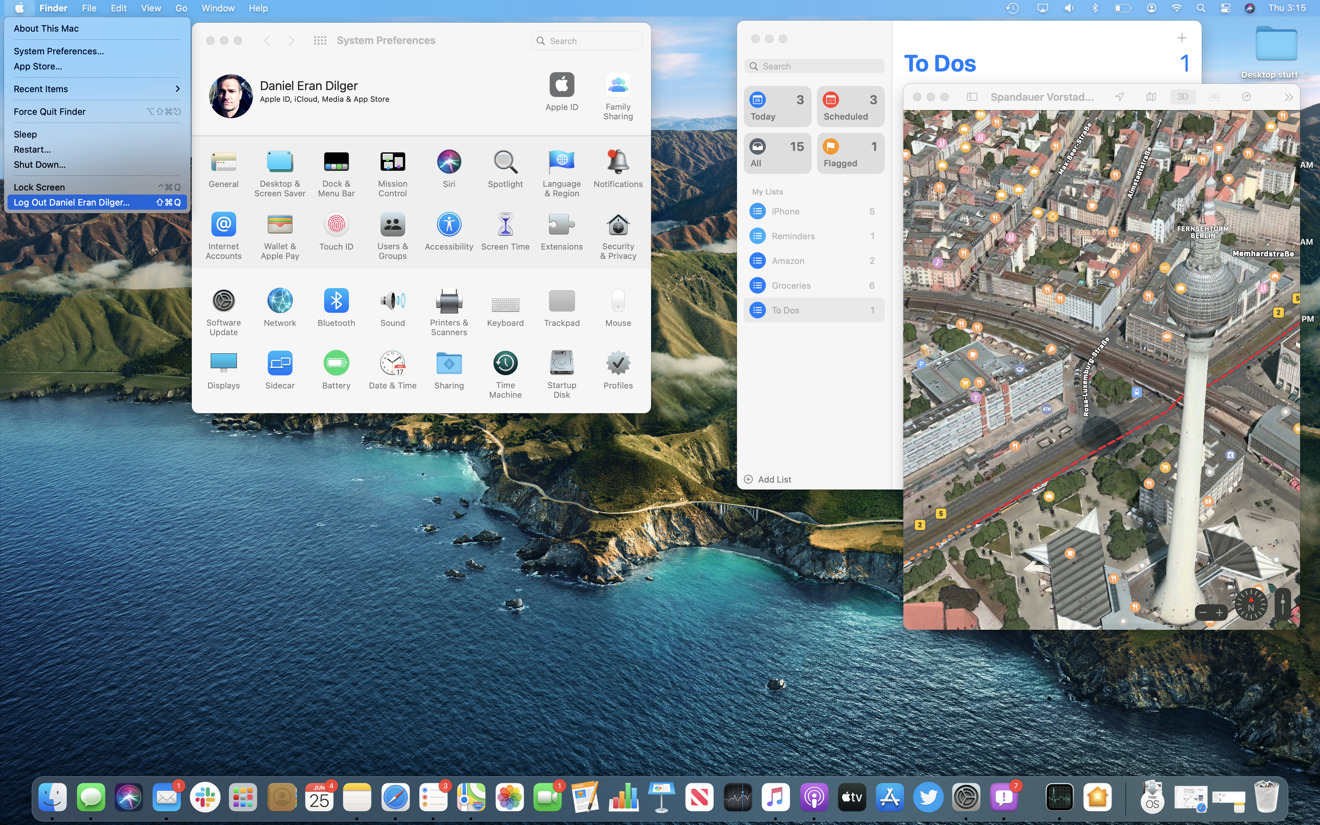

Some have pointed to new UI refinements in Big Sur that look like a modern departure from the Mac’s traditional look with its square panels, rigid alignments, and more dramatic contrast from dark monochrome regions. The default Big Sur desktop in the first beta makes the new and updated look particularly radical due to the use of rich colors (below). Is this the end of the beloved Macintosh? Is it becoming “just a great iPod touch”?

Change the default wallpaper (above) to Big Sur California photo (above) and everything will look less weird and eye-catching.

I do not think so. Instead, I think the changes Apple is making on the Mac are in the right direction, even if they touch that part of the brain that incites fear and worry simply because things are new, different, and a little less familiar. There are some transitional issues and rough edges, like the new battery panel replacing the confusing old “Energy Saver” mess, but this is the first developer beta. Things are still changing and the changes are being resolved.

Apple hired the Google emoji team to make this strange battery of condoms?

Instead of being unhappy because some things on the Mac are changing and horrors! – Reflecting the work that Apple has already done for iPadOS, it is useful to look at things from the other direction. For years, the Mac has received less attention and resources from Apple simply because the market opportunities offered by iPhones and iPads were so much greater.

For the past decade, the work required to deliver the leading smartphone and tablet technology was urgent, while the Mac only needed upgrades to stay comfortably competitive with PCs and netbooks. Three years ago, Apple was consumed with the reinvention of the iPhone X, and since then it has focused on differentiating and radically improving its “new” iPadOS platform.

Back to the Mac

The new Big Sur borrows a series of familiar and functional enhancements from Apple’s years of work that focused on iOS. A great example is the new Control Center, which offers the same clean, intuitive, and configurable design of Quick Settings for Mac.

Big Sur’s new iOS-inspired Control Center is beautiful and shiny

One of Apple’s biggest efforts on last year’s MacOS Catalina was to break up its monolithic iTunes into a series of streamlined, modern apps, reflecting how things worked on iOS. In our review of Catalina, one of the issues we noticed was the increasing lack of visual and user interface consistency across its various included apps, a gap that continued to grow as batches of new apps emerged with their own interface style. fresh with each new version.

Certain old apps seemed to be stuck at different points in the past because they literally were. As Apple’s internal development tools changed over the years, some of the older codes remained difficult to modernize or harmonize with the rest of the system.

Rather than spend the past two years working to update various older macOS components to the Mojave look, Apple began charting a much bolder and more material leap: a jump to its own Apple Silicon in the lowest layer of the stack, as well as a radical new approach to building high-level look and feel in the new Swift user interface. At the same time, Apple also introduced Catalyst as a way to bring existing iOS code to the Mac.

All three represent major investments to improve the Mac platform and prepare it for the future. They expand the library of software that Macs can run while transferring and adapting some of the tremendously valuable UI work that has already been done for mobile devices to Mac desktop systems tuned to handle larger and more complex tasks. These changes really make the Mac more commercially relevant and a stronger platform.

Critics have become obsessed with annoying appearance issues in Catalyst’s early apps and are concerned that Mac’s cherished appearance will disappear. The truth is. The Mac is being modernized more and more, taking advantage of new and more flexible code that supports features ranging from accessibility and internationalization to Dark Mode. Mac stalwarts may be tempted to blame iPad or iOS, but the real force for change is Swift UI, Catalyst, Symbols, and other modern UI techniques and technologies that just appeared first on iPad and iPhone because they were getting the most Apple attention.

Big Sur borrows iOS technology, like Symbols, to improve the Mac and make it more consistent

It’s okay to critically examine the visual changes Apple is introducing in Big Sur, but consider evaluating them as intrinsically positive changes that are not yet finalized. The impact of the Big Sur changes may seem more radical simply because they are applied more consistently across macOS than in previous versions. That in itself indicates that, rather than simply being an arbitrary “new look” for new applications, the changes are a more fundamental rethink of how to keep software modern and sustainable, and therefore more consistent.

At WWDC20, Apple has spent a lot of work showing developers how they can take advantage of the latest tools, particularly Swift UI, to create clean application interfaces that are neat, consistent, and intuitive to use, while still supporting modern functionality and being prepared. to adapt to future functions of the operating system as they are delivered.

.