Campaign strategists and pollsters often speak of an “enthusiasm gap” between parties, suggesting that supporters on one side are more excited about the vote than those on the other. Some, including President Trump, have touted a 2020 enthusiasm lead for Republicans. Is that really the case and what can you tell us about this year’s campaign anyway?

The first thing to know is that surveys measure enthusiasm in a variety of ways, and the way a question is asked can produce different results. Some ask about excitement about a particular candidate, while others ask about excitement about voting more generally.

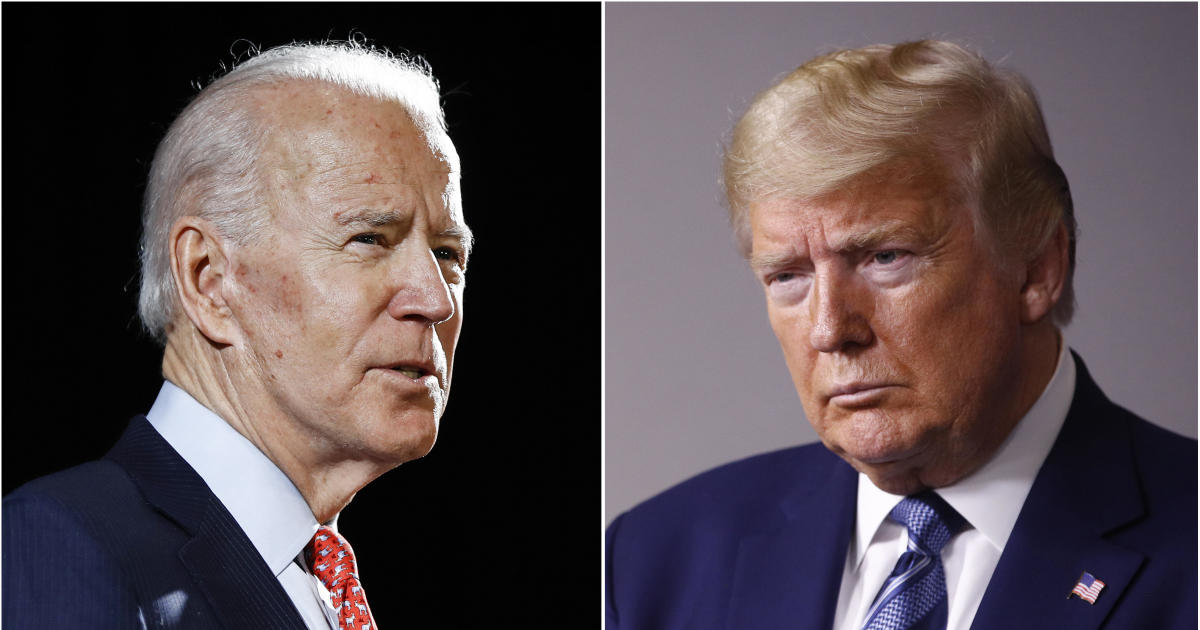

Our recent Battleground Tracker Survey He does the latter, asking voters how they feel about “voting in the November election.” In key battlefield states we’ve surveyed this month, supporters of both President Trump and Joe Biden tend to say they are “very excited” about the vote. However, Trump supporters are more likely to say so by a margin ranging from 2 to 9 percentage points, depending on the state. As shown in the table below, the gap is more pronounced in the Sun Belt states we surveyed earlier this month: Arizona, Texas, and Florida.

While there has been a lot of enthusiasm, it may not be the most important measure this year. A half-hearted vote, of course, counts the same as a half-hearted vote, so this is a useful measure insofar as it indicates who is firmly behind your candidate and who will really turn out this fall.

We measure the strength of each candidate’s support in multiple ways, and these data tell a different story about the 2020 campaign. First we ask how much voters support their chosen candidate.

At the national level, the vast majority of supporters of both candidates say that their support is very strong (78%) or strong (16%). As the chart below shows, Biden has the advantage of this measure in some states, particularly our latest Michigan and Ohio polls (Negative values indicate a Democratic advantage.) However, in Arizona and Texas, they seem very tight races – Mr. Trump leads both the enthusiasm and the support force.

Importantly, even Biden’s supporters who are not very enthusiastic about the vote mostly say their support is very strong, even more so than those who are not very enthusiastic about Trump, indicating that despite his lack of enthusiasm, they have made a decision.

Another way to measure the strength of support is to ask voters how open they are to changing sides. Neither Trump nor Biden’s supporters seem very open to change: nine out of ten say they would never consider the other candidate.

Also, most of them strongly support their candidate and They would never consider the other candidate: 77% of Trump supporters and 74% of Biden supporters say it across the country.

Going back to enthusiasm, the likelihood of voters saying they are very excited is related to the main reason they choose to support their candidate. While most Trump supporters say they vote primarily for him because they like him, about half of Biden voters say the opposition to Trump is driving their vote. Together, this means that in all parties, most voters base their decisions primarily on how they feel about the president. Biden’s sponsors seem to express less enthusiasm, in part, because they are more motivated by dislike for Trump than by loving their candidate.

In summary, our data suggests that while Trump voters are most excited in certain states, other emotions seem to be motivating Democratic voters, who are so strong in their support for Biden. If lack of enthusiasm does not indicate soft support, does it indicate whether or not someone will really bother voting?

The 2018 congressional elections, in which historic levels of turnout fueled a blue wave in the U.S. House of Representatives, offer some clues. In our voteRepublicans and Democrats showed similar levels of enthusiasm. When we contacted them again after the election, we found that their pre-election enthusiasm did little to predict whether they actually voted, at least after controlling for their self-reported probability of participating.

However, Republicans and Democrats constantly differed in two other dimensions that year: anger and the perceived importance of midterms. In competitive districts, Democratic voters were 20 points more likely than Republican voters to say they would be angry if the other party won, rather than disappointed. And Democrats were twice as likely as Republicans to say that the midterm elections were more important than a presidential election. Neither of these sentiments is “enthusiasm” per se, but they were important signs of discontent underlying an increase in participation.

When we surveyed voters in competitive states this year, there appears to be a similar dynamic at play. However, amid a deadly pandemic and evolving procedures and rules for electoral administration, it is much less clear how these sentiments will translate into the number of people who vote.

.