Robyn Beck / AFP via Getty Images

Uber has long been notorious for its hard-hitting business practices, but these days the company is trying to sound like the ridiculous compromise. On Monday, for example, the New York Times published an op-ed by Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, responding to criticism that companies with gig economics are lacking workers on their platforms. While Uber maintains the usual argument – that turning independent employers into employees would deprive them of the freedom to work as much as they want – Khosrowshahi offers what he sees as a third way: new state laws requiring companies like Uber to provide workers’ benefits but not formalize their employment.

However, Uber is not just fighting to maintain its business model on on-ed pages. The powerful, level-playing tone of Khosrowshahi’s piece is believed to challenge the campaign that Uber has funded to resist a landmark California law that requires the company to provide benefits and protection to employees to its drivers. That was underlined in an incident last week. A group formed by Uber and several of its peers has recently taken to a law professor to tweet about her efforts to classify her workers as employees. The Twitter account for Yes on 22, a commission dedicated to promoting the California Voting Proposition 22 that would keep some gig workers as independent contractors, encouraged users to post screenshots of notifications they were blocked by University of California – Hastings Law Professor Veena Dubal. The account retweeted after screenshots of users who pretended to be gig drivers.

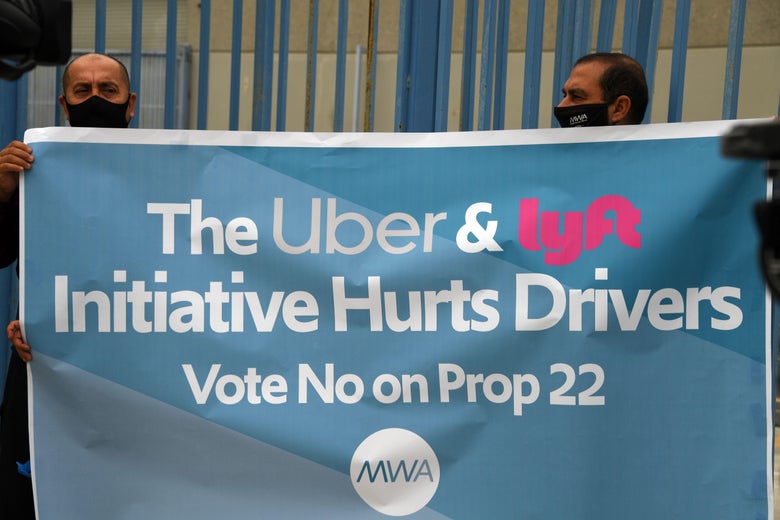

Yes at 22 has about $ 110 million in funding – $ 90 million from Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash, and $ 20 million from Postmaten and Instacart. The commission collected signatures, bought advertisements, and filed a case to get the statement in November. Prop 22 would partially reverse AB5, the California law signed in 2019 that requires companies to redistribute independent contractors as clients. So far, Uber and Lyft have violated the law, which could cost them hundreds of millions of dollars a year if they comply. However, the Superior Court in San Francisco ruled Monday that the companies must begin to comply. Prop 22 could be one of their last chances to escape AB5. That might explain, though not excuse, the spike in Yes on 22’s social media strategy, which evokes an image that Uber has been working to hide since the dismissal of pugnacious CEO Travis Kalanick in 2017. The company was often aggressive against his critics under Kalanick, threatening to dig up filth about journalists and hiring intelligence companies to investigate complainants who have sued the company.

Dubal has been a leading advocate for AB5 and a critic of Prop 22, claiming she will “drive drivers’ inability to predict their income.” She drafted a letter in 2019 urging the U.S. Senate to support AB5 and has been vocal in the media and called for more protections for gig workers (including in Slate). In February, around the time Ja formed at 22, a number of Twitter accounts were fixed about her as the secret ghostwriter of AB5. Although Dubal has supported the legislation, she has not drafted it. On Twitter, she was bombarded with threats and vulgar harassment, often ignoring her identity as a woman of color. Other accounts circulated false rumors about her, claiming she was harassing independent contractors on Twitter. In an interview, Dubal told me that they noticed that some of these accounts had a minimal presence outside of the harassment and were recently registered. (She shared several screenshots; Lei got tired of the usernames of the people who tweeted at Dubal.)

Veena Dubal

Veena Dubal

After someone posted her home address on Twitter in March, Dubal hired a digital security consultant to curb potential threats to her family. ‘That was really scary because it was in the middle of the lockdown. “People knew I was home, and I have three small children,” she said. “It was very easy to find us and potentially hurt us.” In addition to scrubbing her personal information from the web, the consultant also advised her to block more aggressive accounts that harassed or became aggressive in her mention. She says she was also approached offline.

When contacted about the tweet asking to block screenshots, Ja on 22 spokesman Geoff Vetter made a statement: “We may not agree on the policy, but we could do it without our agreement. The “post of the campaign just asked why a drivers’ lawyer silenced the drivers who disagreed. We condemn anyone who harassed Professor Dubal and ask that it stop immediately.” (Uber, Lyft and DoorDash have did not respond to requests for comment.) “This is a really disrespectful response. The account has seen all the harassment there has been,” Dubal said of the statement on Yes on 22. “This particular tweet was intended to to encourage bullying. ” Here is one response to that tweet:

Veena Dubal

Dubal pointed out that she is not a public servant and has no way of knowing whether the people behind the accounts she blocked are actually administrators. She generally does not engage with drivers on social media, but talks to her as part of her ethnographic research into how shifting technologies are affecting the lives of ride-hail drivers in San Francisco. Dubal had never interacted with Yes at 22 prior to the commission that singled her out on Twitter. Shortly before Yes on 22’s account began asking for the screenshots, she had tweeted about the San Francisco Superior Court case, which could explain why she became a target at that moment. “This idea that I don’t listen to drivers is really forgettable,” she said. “As [Yes on 22] effortless to read my research, they would show how deeply I approach with how drivers feel about employment status in particular, and how carefully and critically I consider their life experiences.