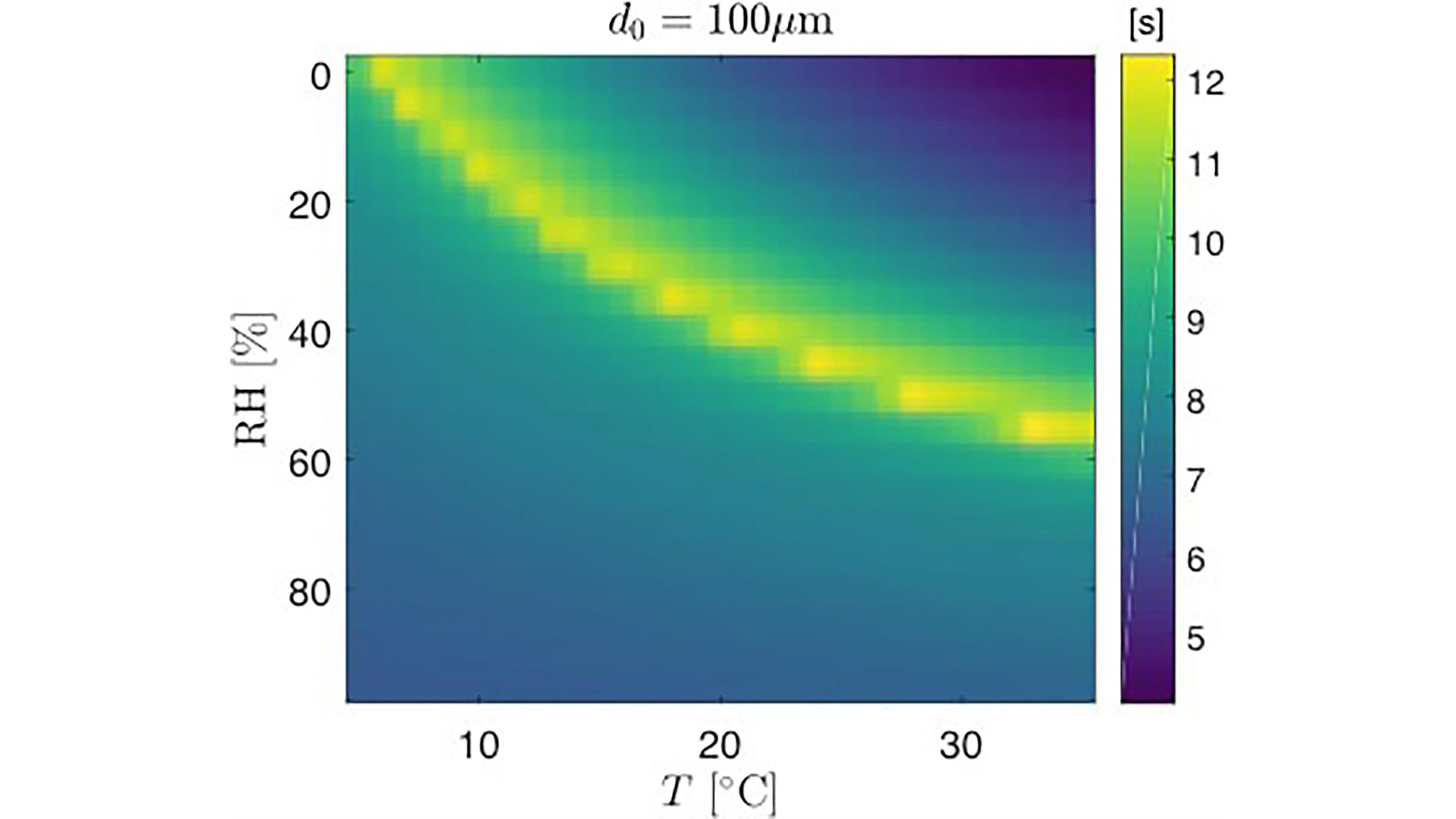

Color chart showing how much time a free-falling 100-micron drop at an initial height of 1.6 meters is affected by temperature and humidity. For relative humidity (RH) and temperatures (T) below the yellow arc, the drop will fall to the ground in the number of seconds indicated by the color scale; above the arc the droplet will completely evaporate into air, and will never reach the ground. Credit: Binbin Wang

Scientists report a detailed model of aerosol transport by air, considering various environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity and environmental current.

The novel coronavirus that causes it COVID-19 is thought to spread through natural respiratory activities, such as breathing, talking and coughing, but little is known about how the virus is transmitted through the air.

Scientists from the University of Missouri report, in Physics of liquids, by AIP Publishing, on a study of how airflow and fluid flow affect extinct droplets that may contain the virus. Their model contains a more accurate description of air turbulence that affects the trajectory of an exhaled droplet.

Calculations with their model give, among other things, an important and surprising effect of humid air. The results show that high humidity can extend the lifespan of medium-sized drops by 23 times.

Drips that exhale in normal human breath come in a range of sizes, from about one-tenth of a micron to 1,000 microns. For comparison, a human hair has a diameter of about 70 microns, while a typical coronavirus particle is less than a tenth of a micron. The most common exhaled droplets are about 50 to 100 microns in diameter.

The droplets exhaled by an infected individual contain virus particles like other substances, such as water, lipids, proteins, and salt. The study considered not only transport of droplets through the air, but also their interaction with the surrounding environment, in particular through evaporation.

The researchers used an improved description of air turbulence to account for natural fluctuations in air currents around the extinct droplet. They were able to compare their results with other modeling studies and with experimental data on particles similar in size and exhaled droplets. The model showed good agreement with data for maize pollen, which has a diameter of 87 microns, about the same size as most of the exhaled droplets.

Moisture affects the fate of exhaled droplets, because dry air can accelerate natural evaporation. In air with 100% relative humidity, the simulations show larger droplets 100 microns in diameter falling about 6 meters from the source of exhalation to the ground. Smaller droplets 50 microns in diameter can travel further, up to 5 meters, or about 16 feet, in very humid air.

Less humid air can slow the spread. At a relative humidity of 50%, none of the 50-micron droplets traveled above 3.5 meters.

The researchers also looked at a pulsating jet model to mimic coughing.

“If the virus load associated with the drops is proportional to the volume, nearly 70% of the virus would be put on the ground during a cough,” said author Binbin Wang. “Maintaining physical distance would significantly remedy the spread of this disease by reducing the deposition of droplets on humans and by reducing the chance of inhalation of aerosols near the infectious source.”

Reference: “Transport and Fate of Human Expiratory Drops – A Model Approach” by Binbin Wang, Huijie Wu and Xiu-Feng Wan, August 18, 2020, Physics of liquids.

DOI: 10.1063 / 5.0021280