The similarities to the case of George Floyd, a black American killed during a police arrest in the American city of Minneapolis, do not end there. Chouviat’s arrest, also captured on video, would become, like Floyd’s, the focus of a broader campaign against police brutality. And as in the Floyd case, action against the officers would seem painfully slow.

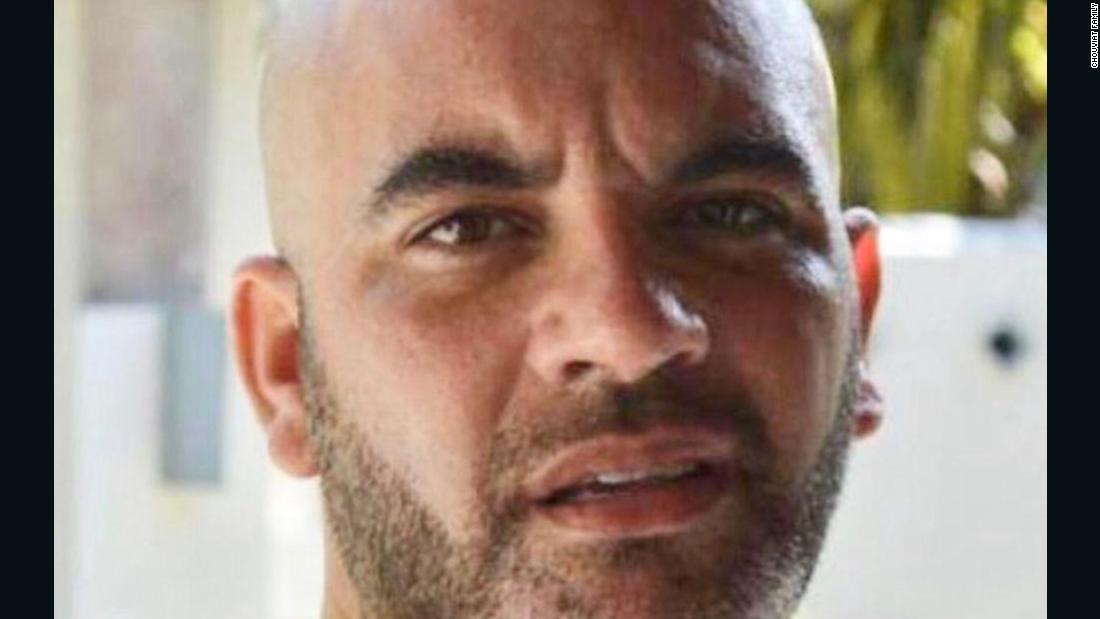

But six months after the death of Chouviat, who was of North African descent, three of the police officers involved have now been placed under formal investigation, lawyers for the Chouviat family told CNN on Thursday. This, after the audio of the incident, captured by Chouviat’s own phone, was presented to the investigating judge. The transcript of the recording, seen by CNN, shows that Chouviat repeated the words “j’etouffe” seven times. An attorney for two of the police officers says his clients never heard the words, since Chouviat was still wearing his motorcycle helmet at the time. The four officers deny that they acted badly.

But four years after the 24-year-old black man’s death, no charges were filed against the officers involved. His lawyers point to a medical evaluation that attributes Traoré’s death to a pre-existing condition that his family says he did not have.

What the two cases have highlighted is the difficulty families of victims face in obtaining allegations of police brutality properly and promptly investigated. According to William Bourdon, a lawyer for the Chouviat family, France “increasingly resembles the United States because of the persistence of police brutality and the denial that comes with it.”

A spokesman for the Paris police service declined to comment to CNN.

Both cases have also led to demands for a change in police techniques. In Traoré’s case, officers used a controversial technique that involves immobilizing a suspect in the stomach. In Chouviat’s case, the allegations focus on the use of the choke. Last month, under pressure from police unions, plans to ban the technique were shelved by France’s then Interior Minister Christophe Castaner. That he had even considered the move was unpopular with the police, who held several protests in June against him. On Monday, he was replaced as interior minister on July 6 as part of a broader government reorganization.

As in the United States, there is a culture of resistance in the police force to the investigation of other officers, as well as resistance by strong police unions to attempts at reform.

All the more so because of his role in recent years in France to help the government quell the yellow vest protests by bringing order to the streets of France once again. Some activists say the police have simply become too powerful. “I think outrage, anger and sometimes violence are fueled by this systematic rejection of any accusation,” said Cecile Coudriou, President of Amnesty International in France.

“And the more the authorities stick to this rejection of any accusation, the more they try to reject dialogue, even with us, with people who work on the basis of evidence, the worse it becomes because it means that people lose confidence in the authorities and they lose confidence in the people they are supposed to do not only to enforce the law but also to protect people. “

Lack of data on race or ethnicity

Another difficulty, and specific to France, is the impossibility of quantifying racist incidents. France’s public institutions do not collect data on race or ethnicity, in a laudable effort to treat all citizens equally.

But this law has led to a lack of data, making it difficult for non-white French to make white French aware of the very different reality they face. As one activist, Rhoda Tchokokam said, “People tell you that because of race, religion, gender, they are being discriminated against. If you can’t face it, you’re basically telling people in their country that they don’t see them and that they don’t care. So it is very important that the French state understands that we are going to keep talking about it. And they must start doing the same. “

Furthermore, activists say, because while the French state may not see the color, the police apparently do. Non-white French say they are subject to identity checks much more than whites. Ben Achour, a lawyer specializing in police brutality and discrimination, said the checks are being misused.

“What the police do,” said Ben Achour, “is more than chasing criminals, they check to see if you are really French. And that also allows for frisking, violence, insults and insults. That is the condition of The lives of many children in France. They are subject to such actions several times a week. How can they develop their self-esteem? How can they trust the Republic? How can they not challenge the Republic when it is one of the first institutions? are you in contact when you are 10, 11, 12, 13 years old, is he violent with you? “

Until now, due to data law, the problem has been impossible to quantify and the evidence was purely anecdotal. But last month, a report by the French civil liberties ombudsman, former justice minister Jacques Toubon, warned that black and Arab-looking people were subject to police identity checks 20 times more frequently than white people .

For Achour, this first recognition of the problem by a French institution is a great step. He told CNN that what Toubon had found was “great systemic structural discrimination in France. And he says we must count it. We need to measure this discrimination. You can’t fight discrimination, you can’t create policies if you don’t have a measure ” because otherwise the problem does not exist. And that is why the moment is very important. Now we have momentum in France. “

That momentum has been helped by events in the United States. The death of George Floyd and national calculations in the United States have given new hope to supporters of the Chouviat and Traoré families with several protests in recent weeks in France. Their slogan “Black Lives Matter” may have been imported, but they have been fueled by cases and complaints that are entirely French.

CNN’s Barbara Wojazer contributed to this report.

.