Written by Eon Muskuni, CNNLondon

A painting of an African former slave who became the daughter of Queen Victoria has been unveiled at Osborne, on the shores of the former British monarch.

The work, written by Hanna Uzor, is part of a series of portraits detailing the lives of previously neglected black figures that will be donated by the charity English Heritage.

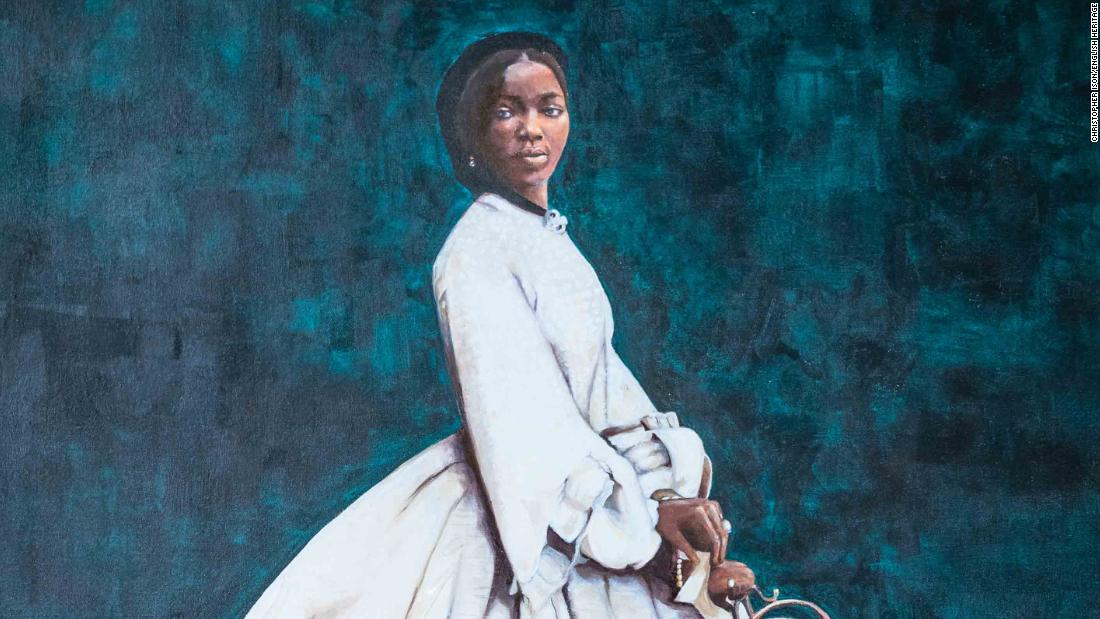

Bonnetta’s painting by artist Hannah Uzore (pictured) is on display at Osborne during the month of Black History during October. Deposit: Christopher Eisen / English Heritage

It shows Sarah Forbes Bonnetta in her wedding dress and is based on a photograph from the National Portrait Gallery in London. It will be screened in Osborne during October, which is Black History Month in the UK.

Bonnetta was the daughter of an African ruler who was sold into orphanage and slavery at the age of five, according to English Heritage, who cares for more than 400 historic buildings, monuments and sites.

Originally named Omoba Eye, it was presented as a “diplomatic gift” to British Navy Captain Frederick Forbes and was brought to England.

A few months after his arrival in England, Forbes introduced Bonta to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. The second longest-serving king of the UK wrote in his journal in 1851 that Bonetta was “really an intelligent little thing.” Forbes described him as “a complete genius” with “the best talent in music” in the ship’s diary.

The queen paid for his education and became his godmother. Bonnetta married James Davis, a merchant born in Sierra Leone in 1862, and their first daughter was named after the king, who also became her godmother.

They remained close throughout Bonetta’s life and Victoria continued to follow the progress of her children, whom she met many times. In a journal entry in 1873, Victoria wrote: “Sally Davis’ little girl, Victoria, now 8 years old, and, like her mother, very dark and beautiful-eyed.”

When Bonnetta died in 1880, little Victoria sought rest from the Queen of Osborne, the English Heritage said in a statement on Wednesday.

“Through my art, I am interested in finding such forgotten black people in British history, people like Sarah,” Uzore said. “What I find interesting about Sarah is that she challenges our perceptions about the status of black women in Victorian Britain. I was also attracted to her because of my similarities with my own family and my children, who share Sarah’s Nigerian heritage.”

English Heritage said it plans to display more portraits of other black figures next spring, with links to some of the historic landmarks under its care. These include the African-born emperor of Rome, Septimius Severus, who fortified Hadrian’s wall, and the servant James Chapel in Kirby Hall, who saved the owner’s life.

“These stories are far behind and we look forward to hearing from them,” Anna Evis, curatorial director of English Heritage, told CNN on Wednesday. “It is important and possible for the island to act as a vehicle for visual images in many cases where different cultures have been welcomed or received.”

Black History is “part of English history,” she added, and the English Heritage Portrait series is part of research into links between sites in the slave trade and charity care. From 2021, new interpretations on specific sites will emphasize those links.

The news comes after another charity, the National Trust, admitted in an interim report in September that it cared about historic historic sites with links to colonialism and slavery. About 26 properties of the English heritage are linked to the slave trade, according to a 2007 report released by the charity.

“Britain’s black history is by its very nature a global history,” said David Olsoga, a British historian in his book “Black and British: A Forgotten History.” Yet, more often than not, it is seen as merely a history of migration, reconciliation and community building in Britain. ”

In an essay he presented on BBC radio last year, he said Bonnetta’s story was “so remarkable” that he “found it hard to believe when it first came out.”

.