Over the past week, I’ve been seeing quite a few websites promoting an eclipse of full moon on the night of the Fourth of July holiday in the United States.

A website even went so far as to list lunar eclipse among the top 10 heavenly “not to be missed” events of 2020. AND USA Today has said: “If your fireworks display is canceled on July 4 of this year due to the coronavirus, there is still something in the sky to look for over the weekend: a lunar eclipse.”

Related: July full moon 2020: lunar eclipse ‘Buck Moon’ meets Jupiter

So, as a public service to those of you who might have been eager for this upcoming celestial event, take it for me: if this eclipse is lost, it won’t be a big deal.

In fact, even if you are looking, you are going to miss it. It’s certainly a poor consolation prize compared to an already canceled fireworks show.

Now you may be a little confused at this point … in fact there will be a late lunar eclipse on Saturday night. The only problem is that the eclipse will take place right before your very eyes and you will not notice anything.

The reason? Is a penumbral Lunar eclipse.

Literally defined, an eclipse is: “A darkening of the light of one celestial body (in this case, the moon) by the passage of another (Earth) between it and the observer, or between it and its source of illumination (the sun) “, according to the Oxford Dictionary.

So let me explain how our closest neighbor in space can be “overshadowed” and yet, in this case, actually not be hidden.

Two shades for the price of one

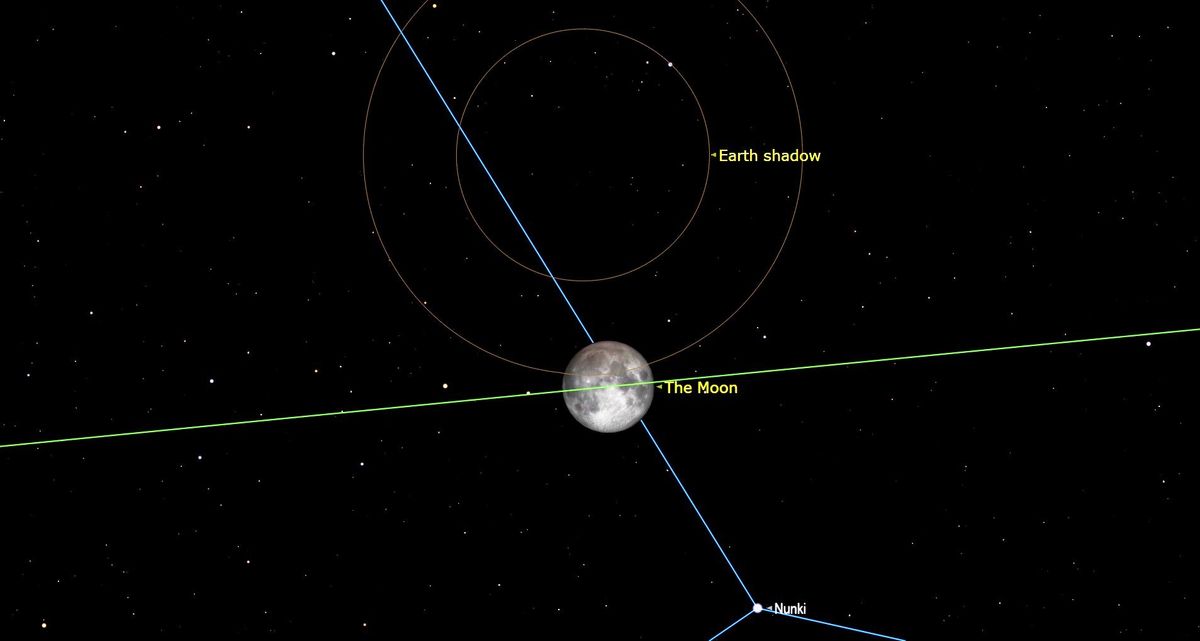

Very often, with an impending eclipse of Moon It is coming, we are told that the moon will be eclipsed by the shadow of the Earth. But to be strictly precise, the Earth does not throw one but two shadows in space. Most notable is a dark, thin, conical cone of darkness that stretches out into space for about 857,000 miles (1.38 million km), called the umbra.

During a lunar eclipse, where the umbra falls on the surface of the moon, a hypothetical astronaut who could be located on that part of the moon would see Earth completely cover the sun’s disk and would therefore sink into darkness. Looking from here on Earth, we would see the projected umbra as a curved area of darkness, dramatically cutting the face of the moon; to the ancients it seemed as if an invisible monster was “biting” the moon.

Around the umbra is the penumbra, or partial shadow, also conical but much larger.

The half-light is simply the half-shadow that lies outside each deep shadow, whether cast by the Earth or a house. If our hypothetical astronaut were located just outside the edge of the umbra, he or she would be very deep in the gloom; Looking up from the lunar surface, they would see Earth covering everything but a narrow swath of the sun in the lunar sky. And looking in all directions, the lunar landscape lighting would seem remarkably dim.

Related: How lunar eclipses work (infographic)

Low profile darkening

Eclipse stages

The penumbral eclipse begins: 11:07 pm EDT (0307 GMT).

Maximum eclipse: 12:30 am EDT (0430 GMT)

The penumbral eclipse ends: 1:52 am EDT (0553 GMT).

It is not complete darkness, but still, the general lighting coming from that remaining sunbeam would be considerably dimmer than normal. And from here on Earth, looking towards the moon while not seeing a closed curve of darkness, we would rather notice that a part of the moon seemed somewhat “tarnished” or “stained”. That’s usually all that is noticeable during most penumbral lunar eclipses, just very subtle shading.

But you won’t even see this.

On Saturday night, the moon will partially graze the southern part of the twilight. That means the top of the moon will be in the shadow of the twilight. However, the geometric magnitude of this eclipse appears as 0.3546. That means that just over a third of the moon’s diameter will be within the so-called “half-shadow” at the time of the maximum eclipse.

Related: Lunar eclipse 2020 guide: when, where and how to see them

No noticeable change

Do you see the lunar eclipse?

If you see the Buck Moon 2020 lunar eclipse, please let us know! Send images and comments to [email protected] to share your views.

Then the lower two thirds of the moon will be completely out of the shadow of the twilight. How about the top third? Can we notice any darkening?

The answer is a very definite “no”. If our hypothetical astronaut were located on the lunar surface in the region north of Mare Frigoris (the “Sea of Cold”), they would see Earth covering about a third of the sun. But that would have no noticeable effect on darkening the lunar landscape; everything would look more or less the same without the sun being covered.

And as seen from here on Earth at that time, at 9:30 pm PDT or 12:30 amEDT on Sunday (0430 July 5 GMT), if you are looking at the moon you most likely will not see .. . nothing.

Yes, calendars and almanacs are correct. The moon is officially full and at that time it will undergo an eclipse.

It’s just that the passing of the moon on Saturday will take you through an extremely weak part of the gloom, and as such the moon will retain its normal appearance.

A better option

In general, most people don’t notice the penumbral shadow cast on the moon until at least 70% of its diameter is covered. Some people who have very sharp vision and better-than-average perception may notice very slight shading when only 50% of the moon is in half-light.

But in the case of Saturday night, the darkening amounts to just over 35%; it is not enough to cause any kind of visual impact.

If you really want to see a penumbral eclipse that will have an impact (more or less), you won’t have to wait too long.

On November 30, very early that Monday morning (the hours before sunrise) another penumbral lunar eclipse will take place. However, this time the geometric magnitude will be 0.8285, or more than four-fifths of the moon’s diameter will be within twilight at maximum eclipse, which will likely result in noticeable shading of the top of the moon.

However, it is undoubtedly still a very “disappointing” event.

Editor’s Note: If you capture a photo of the lunar eclipse and want to share it with Space.com for a story or gallery, send images and comments to [email protected].

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and visiting professor at the Hayden Planetarium in New York. He writes about astronomy for the Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac, and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.