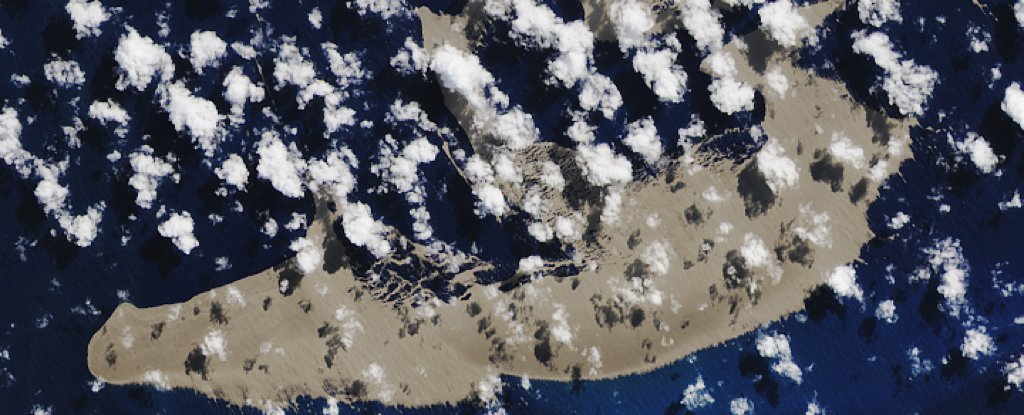

A giant float of floating rocks, ejected from an underwater volcano in the Pacific Ocean, drifted thousands of miles across the waves. Eventually it made it all the way to Australia, and then embarked on a new project: revitalizing the world’s largest (and highly endangered) coral reef system.

This unlikely chain of events may sound unbelievable, but it’s a completely true story – one that has played out dramatically over the last year, while repeating the surprising, mostly invisible ways in which the earth’s natural environmental systems cross each other.

Stranger still, it is not the first time this has happened. An eruption in 2001 from the same submarine submarine – an unnamed volcano, simply called Volcano F as 0403-091, located near the Vavaʻu Islands in Tonga – produced a similar rocky flotilla, which also flows up to Australia traveled over the space of a year.

When this phenomenon occurs, it creates what is called a pubertal flight – a floating platform consisting of innumerable parts of floating and highly porous volcanic rock.

Each of these small rocks attracts marine organisms, including algae, children, corals, and more. These little travelers end up with a ride across the ocean, and they can help sow and replenish endangered coral systems at their ultimate destination: for many, the Great Barrier Reef.

“Each piece of puberty has its own little community that is transported across the oceans of the world – and we have driven vibrations of pieces of this pumice to the eruption,” says geologist Scott Bryan of Queensland University of Technology in Australia .

“Every piece of puberty is a house, and a car for an organism, and it’s just amazing. The sheer number of people and this variety of species being transported thousands of miles in just a few months is really quite phenomenal.”

Bryan knows a thing or two about these adolescent migrations. He spent 20 years researching volcanic eruptions, examining the 2001 eruption, his 2019 successor (which began washing on Australian shores in April), as well as other underwater eruptions.

His most recent study, published last month, examined the 2012 eruption of the Havre Seamount, also in the South Pacific – estimated to be the largest underwater volcanic eruption ever recorded, broadly equal to the most powerful volcanic eruption on country in the 20th century.

That event produced a giant hull pumice stone that eventually drifted over an area twice the size of New Zealand – in addition to the sea flower with giant pieces of pumice occupying the size of vans.

Geologist Scott Bryan with a pumice stone. (QUT)

Geologist Scott Bryan with a pumice stone. (QUT)

“We do not understand why some adolescents sink during the eruption at the site and others can float on the oceans of the world for many months and years,” Bryan says, but further analysis could fill the gaps.

“This will help us understand the mechanisms and dynamics of these explosive eruptions and better understand why these eruptions produce potentially dangerous pubertal flights.”

Potentially dangerous is equal. Last year’s eruption from Volcano F produced some amazing video of what it’s like to sail in these giant rafts, resembling giant oil rigs, made only of upwelling rocks that seem to go on forever.

These surrealistic, drifting formations are not inherently dangerous in themselves, but they could have the potential to damage boats, and in some circumstances could spill over shoreline, as another video from this year attests.

For now, though, researchers hope the latest delivery of Volcano F will do some good for the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia, which will be besieged by coral reefs as the world’s oceans heat up due to climate change.

While the organisms that carry the rocket flotilla can help replenish reef ecosystems, scientists are afraid to stress that they are not silver bullets.

“Pumice rafts alone will not directly reduce the effects of climate change on the Great Barrier Reef,” says Bryan.

“This is about an impetus of new recruits, of new corals and other reef-building organisms, that happens every five years or so. It’s almost like a vitamin shot for the Great Barrier Reef.”

And possibly even much further away. The puberty of 2019 – which a year ago covered some 20,000 football pitches in size – can now be found all the way along the Australian east coast from Townsville in Queensland’s north to northern New South Wales: spread over more than 1,300 kilometers of coastline.

It is a massive spread, originating from one event far beyond the horizon, and one that serves to remind us of the bonds between what often seem to be just different marine ecosystems.

“This shows that the Great Barrier Reef has connections with coral reefs that are thousands of miles further east,” Bryan says.

“As far as the health of the Great Barrier Reef is concerned, it is also important that these distant reefs are taken care of.”

Geologist Scott Bryan examines pumice. (QUT)

Geologist Scott Bryan examines pumice. (QUT)

As for Volcano F, it has increased its profile in recent years, and in more ways than one. The persistent eruptions not only attract the attention of scientists – they also change and build up the underwater landscape around the volcano.

Bryan was part of an expedition team that explored the site this year, collecting samples and observing what the volcano looked like under the waves.

“It’s a volcano coming close to breaking the surface and will become an island in the coming years,” Bryan says.

We’ve seen what that might look like in other parts of the world, and it’s a pretty fantastic spectacle: instead of giant volcanic rafts, huge pop-up islands appear from the ocean.

Volcano F was already a great story, but it seems that the next chapter may be even more unbelievable.

.