The sturgeon, a long-lived bottom fish, is often described as “living fossils” because its shape has remained relatively constant, despite hundreds of millions of years of evolution.

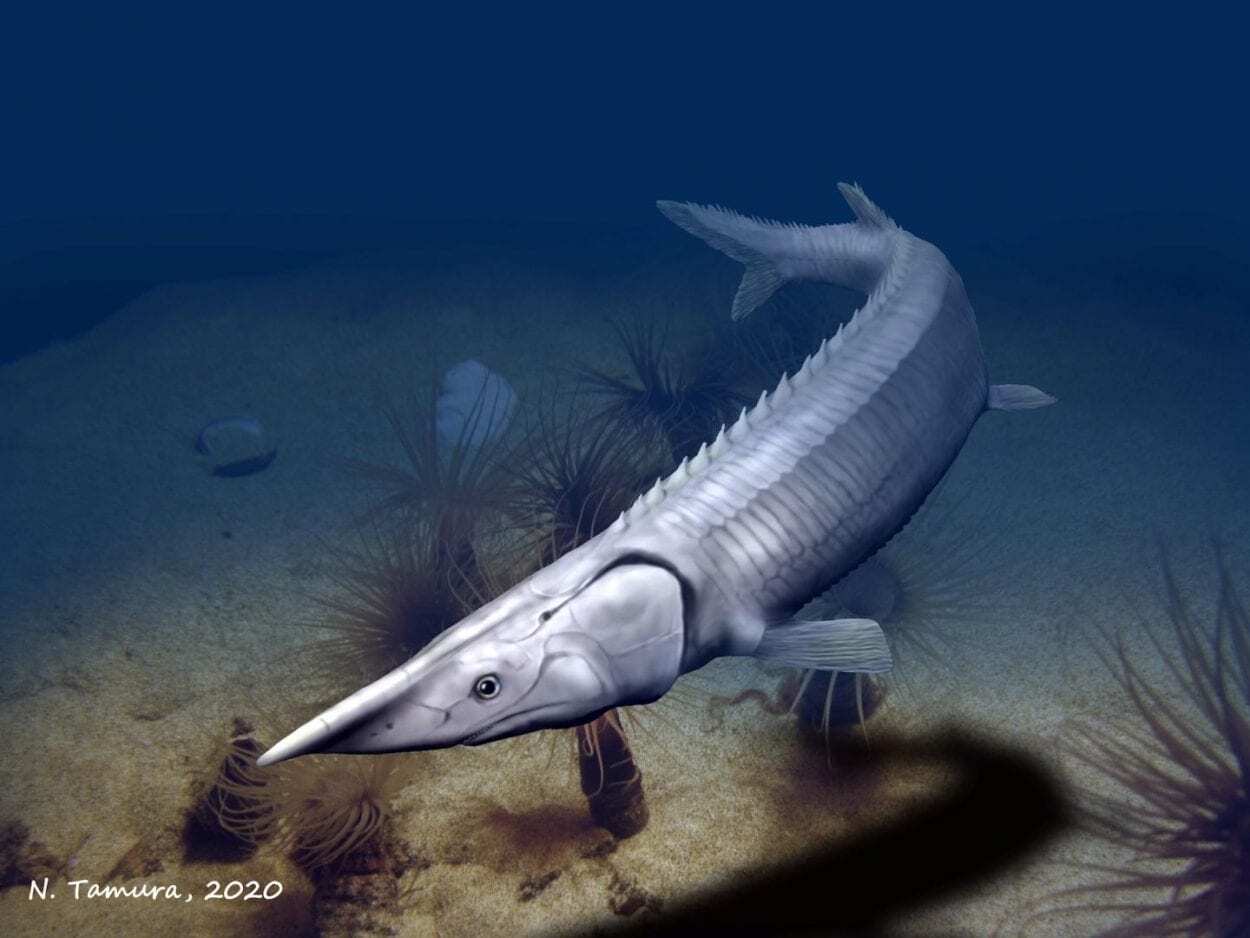

In a new study in the Linnean Society Zoological Magazine, researchers led by Jack Stack, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania in 2019, and paleobiologist Lauren Sallan of the Penn School of Arts and Sciences, closely examine the ancient species of fish Tanyrhinichthys mcallisteri, which lived about 300 million years ago. in an estuary in what is now New Mexico. Although they find that the fish is very similar to sturgeons in its characteristics, including its protruding snout, they show that these characteristics evolved on a different evolutionary path from the species that gave rise to modern sturgeons.

The finding indicates that, while ancient, the characteristics that enabled Tanyrhinichthys to thrive in their environment emerged multiple times in different lineages of fish, an explosion of innovation that was previously not fully appreciated by fish in this time period.

“The sturgeon is considered a ‘primitive’ species, but what we are showing is that the sturgeon lifestyle is something that it has been selected for under certain conditions and has evolved over and over again,” says Sallan, lead author of the job.

“Fish are very good at finding solutions to ecological problems,” says Stack, the study’s first author, who worked on the research as an undergraduate at Penn and is now a graduate student at Michigan State University. “This shows the degree of innovation and convergence that is possible in fish. Once their numbers increased enough, they began to produce new morphologies that we now see to have evolved numerous times throughout the history of fish, under similar ecological conditions. “

The first Tanyrhinichthys fossil was found in 1984 in an area rich in fossils called the Kinney Brick Quarry, approximately half an hour east of Albuquerque. The first paleontologist to describe the species was Michael Gottfried, a member of the Michigan state faculty who now serves as Stack’s advisor for his master’s degree.

Subscribe to more articles like this by following our Google Discovery feed: click the Follow button on your desktop or the star button on your mobile. Subscribe

“The specimen looks like someone found a fish and just pulled on the front of its skull,” says Stack. Many modern fish species, from swordfish to sailfish, have protruding snouts that extend in front of them, often aiding in their ability to lash out at prey. But this feature is much rarer in ancient fish. In the 1980s, when Gottfried described the initial specimen, he postulated that the fish resembled a pike, an ambush predator with a longer snout.

Over the past decade, however, several more specimens of Tanyrhinichthys have been found in the same quarry. “Those findings were a boost for this project, now that we had better information on this enigmatic and strange fish,” says Stack.

As Tanyrhinichthys roamed the waters, the Earth’s continents joined together on the massive supercontinent called Pangea, surrounded by a single large ocean. But it was also an ice age, with ice on both poles. Just before this period, the fossil record showed that the finned fish that now dominate the oceans were exploding in diversity. However, 300 million years ago, “it was as if someone pressed the pause button,” says Sallan. “There is an expectation that there will be more diversity, but not much has been found, probably due to the fact that there just hasn’t been enough work in this time period, especially in the United States, and particularly in the western United States. . . “

Aiming to fill in some of these gaps by further characterizing Tanyrhinichthys, Stack, Sallan, and their colleagues, they closely examined the specimens in detail and studied other species dating from this time period. “This sounds very simple, but it is obviously difficult to execute,” says Stack, since fossils compress flat when preserved. The researchers deduced a three-dimensional anatomy using the shapes of modern fish to guide them.

What they noticed cast doubt on Tanyrhinichthys’ conception as a pike. While a pike has an elongated snout with its jaws at the end, allowing it to rush its prey head-on, Tanyrhinichthys has an elongated snout with its jaws at the bottom.

“The entire shape of this fish is similar to that of other bottom inhabitants,” says Stack. Sallan also noted canal-shaped structures in his snout concentrated at the top of his head, suggesting where sensory organs would join. “These would have detected vibrations to allow the fish to consume their prey,” says Sallan.

The researchers noted that many of the species that inhabited similar environments had longer snouts, which Sallan called “like an antenna for their faces.”

“This also makes sense because it was an estuary environment,” says Sallan, “with large rivers that feed it, stir the water and make it cloudy. Instead of using your sight, you have to use these other sensory organs to detect prey.” .

Despite this, other characteristics of the morphology of the different ancient fish were so different from Tanyrhinichthys that they do not seem to have shared a lineage with each other, nor does the modern sturgeon descend from Tanyrhinichthys. Instead, long snouts seem to be an example of convergent evolution, or many different lineages, all coming to the same innovation to adapt well to their surroundings.

“Our work, and paleontology in general, shows that the diversity of life forms that are evident today has roots that extend back into the past,” says Stack.

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

– Advertising –