It is one of the largest studies of its kind, thanks in part to the massive 23andMe client database from which researchers were able to recruit consenting participants.

The authors compiled genetic data from more than 50,000 people from the Americas, Western Europe, and Atlantic Africa, and compared it to historical records of where enslaved people were taken and where they were enslaved. Together, the data and records tell a story about the complicated roots of the African diaspora in the Americas.

For the most part, the DNA was consistent with what the documents show. But, according to the study authors, there were some notable differences.

Here is some of what they found and what it reveals about the history of slavery.

Shows the legacy of rape against slaves woman

The enslaved workers who were taken out of Africa and brought to the Americas were disproportionately male. However, genetic data shows that enslaved women contributed to gene accumulation at a higher rate.

In the United States and parts of the Caribbean colonized by the British, African women contributed 1.5 to 2 times more to the gene pool than African men. In Latin America, that rate was even higher. Enslaved women contributed to the gene pool in Central America, the Latin Caribbean and parts of South America between 13 and 17 times more.

To the extent that people of African descent in the Americas were of European descent, they were more likely to have white fathers in their lineage than white mothers in all regions except the Latin Caribbean and Central America.

What that suggests: Biases in the gene pool towards enslaved African women and European men point to generations of rape and sexual exploitation against enslaved women by white owners, authors Steven Micheletti and Joanna Mountain wrote in an email to CNN.

That enslaved black women were often raped by their masters “is not a surprise” to any black person living in the United States, says Ravi Perry, a professor of political science at Howard University. Numerous historical accounts confirm this reality, as the study authors point out.

But the regional differences between the United States and Latin America are what attracts attention.

The United States and other former British colonies generally forced enslaved people to have children to support the workforce, which may explain why the children of a enslaved woman were more likely to have a slave father. Segregation in the United States could also be a factor, the authors theorized.

On the contrary, the researchers point out the presence of racial whitening policies in several Latin American countries, which brought European immigrants with the aim of diluting the African race. Such policies, as well as the higher death rates of enslaved men, could explain the disproportionate contributions to the gene pool of enslaved women, the authors wrote.

Sheds light on the intra-American slave trade

According to the study, far more people in the US and Latin America are of Nigerian descent than expected, given historical records of enslaved people who shipped from ports throughout present-day Nigeria in the Americas. .

What that suggests: This is most likely a reflection of the intercolonial slave trade that occurred largely from the British Caribbean to other parts of the Americas between 1619 and 1807, Micheletti and Mountain wrote.

Once enslaved Africans reached the Americas, many were put on new ships and transported to other regions.

“Documented travel within America indicates that the vast majority of enslaved people were transported from the British Caribbean to other parts of the Americas, presumably to maintain the slave economy, as the transatlantic slave trade was increasingly prohibited” , the authors wrote in the study.

When enslaved Nigerian people who arrived in the British Caribbean were traded to other areas, their ancestry extended to regions that did not directly trade with that part of Africa.

It shows the terrible conditions. facing enslaved people

By contrast, the ancestry of the Senegal and Gambia region is underrepresented given the proportion of enslaved people who boarded from there, Micheletti and Mountain said.

The reasons for that are bleak.

What that suggests: A possible explanation that the authors gave for the low prevalence of Senegalese descent is that over time, more and more children in the region were forced to embark to make the trip to the Americas.

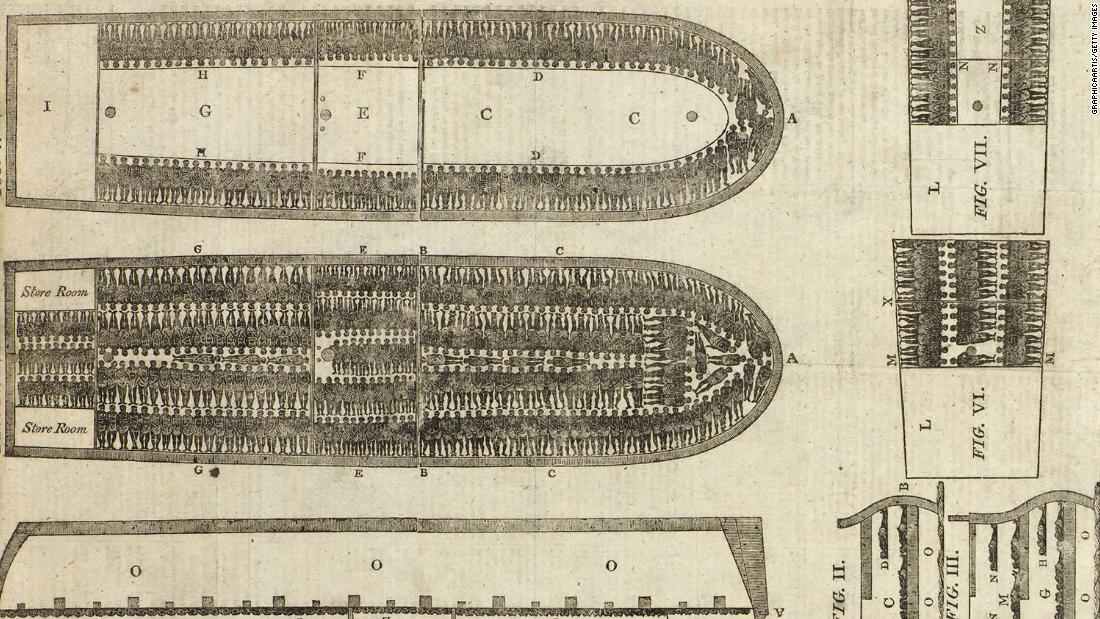

Unhealthy conditions in the ship’s holds led to malnutrition and illness, the authors wrote, meaning they survived less.

Another possibility is the dangerous conditions faced by enslaved people from the region once they arrived. A significant proportion of Senegambians were taken to rice plantations in the United States, which were often rampant with malaria, Micheletti and Mountain said.

The study has limitations.

The 23andMe study is significant in how it juxtaposes genetic data with historical records, as well as the size of its data set, experts who were not involved in the study told CNN.

“I don’t know anyone who has done such a complete job of putting these things together, by far,” said Simon Gravel, professor of human genetics at McGill University. “It is great progress.”

Still, he said, the research has its limitations.

To perform their analysis, the scientists had to make “many simplifications,” said Gravel. The researchers broke down African ancestry into four corresponding regions on the continent’s Atlantic coast: Nigerian, Senegalese, West African coastal, and Congolese.

“That doesn’t tell the whole story,” added Gravel, although he said more data is needed in the broader field of genomics for researchers to dig deeper.

Jada Benn Torres, a genetic anthropologist at Vanderbilt University, also said she would have liked to see a higher proportion of people from Africa included in the study. Of the more than 50,000 participants, around 2,000 were from Africa.

“From the perspective of human evolutionary genetics, Africa is the continent with the greatest genetic diversity,” he wrote in an email to CNN. “To properly capture the existing variation, the sample sizes must be large.”

But both Gravel and Benn Torres called the study an exciting start that offers more insight into the descendants of enslaved Africans.

And that, according to the researchers, was what they set out to do.

“We hope this document will help people of African descent in the Americas better understand where their ancestors came from and what they overcame,” wrote Micheletti.

“… For me, this is the point, establishing a personal connection with the millions of people whose ancestors were forced from Africa to the Americas and not forgetting what their ancestors had to endure.”

.